Tom Williams/AP

If President Donald Trump interferes with special counsel Robert Mueller’s inverstigation or fires him, what should Congress do? According to Brett Kavanaugh, Congress ought to impeach him. At least that’s what he said two decades ago.

During Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings, Trump’s latest Supreme Court nominee refused to answer questions about issues of presidential power that could well be tested in the coming months. He declined to say whether he believes a president can pardon himself. (Referring to Mueller’s investigation, Trump in June declared that he could.) Kavanaugh would not say whether a president can be compelled to respond to a subpoena. (It’s possible that Mueller might resort to one to obtain testimony from Trump.) With these matters potential court cases that could reach the Supreme Court, Kavanaugh kept mum. Yet years ago, Kavanaugh asserted that a sitting president could not be indicted. (If a chief executive cannot be be indicted, he probably can resist a subpoena.) And perhaps surprisingly, Kavanaugh at the same time said that a president who thwarted or fired a special counsel should be impeached.

Kavanaugh shared these sentiments at a 1998 panel discussion sponsored by the Georgetown Law Journal and the American Bar Association.

The topic at hand was the future of the Independent Counsel Act, which was up for renewal the following year. That law established a process for a panel of three judges, at the request of an attorney general, to appoint independent counsels to investigate possible wrongdoing that might involve high-level federal officials. Kavanaugh, who had been part of independent counsel Kenneth Starr’s probe of Bill Clinton (which began as an examination of the Clintons’ role in an Arkansas land deal and morphed into the Monica Lewinsky investigation), had by this point become a critic of the independent counsel process. In a law review article, he had complained that independent counsel investigations often went beyond their original jurisdiction—a complaint that the Clintons and their allies had hurled at the Starr investigation—and that such investigations had become “politicized.”

In that article, Kavanaugh proposed changes. He contended that an independent counsel should be appointed by a president and confirmed by the Senate. He wrote, “Appointment by the President, together with confirmation by the Senate, would provide greater public credibility and moral authority to the independent counsel and would dramatically diminish the ability of a President and his surrogates, both in Congress and elsewhere, to attack the independent counsel as ‘politically motivated.'” Kavanaugh argued that it should be totally up to the president to decide when it was necessary to appoint an independent counsel and that the president and the attorney general should define and monitor the independent counsel’s jurisdiction. And he added that Congress should establish that a president only could be indicted after leaving office or being impeached.

At the 1998 panel, Kavanaugh explained his proposal, noting that this process would provide greater accountability and offer an independent counsel “insulation” from political attacks. Kavanaugh pointed out that a “wise” president would “oversee the special prosecutor at arm’s length” and that Congress would oversee how the president manages this task.

But what if the president messed with the special prosecutor? Kavanaugh had a harsh remedy: booting the president. If the president “interferes or fires the prosecutor,” he said, “impeachment proceedings would not be far behind.”

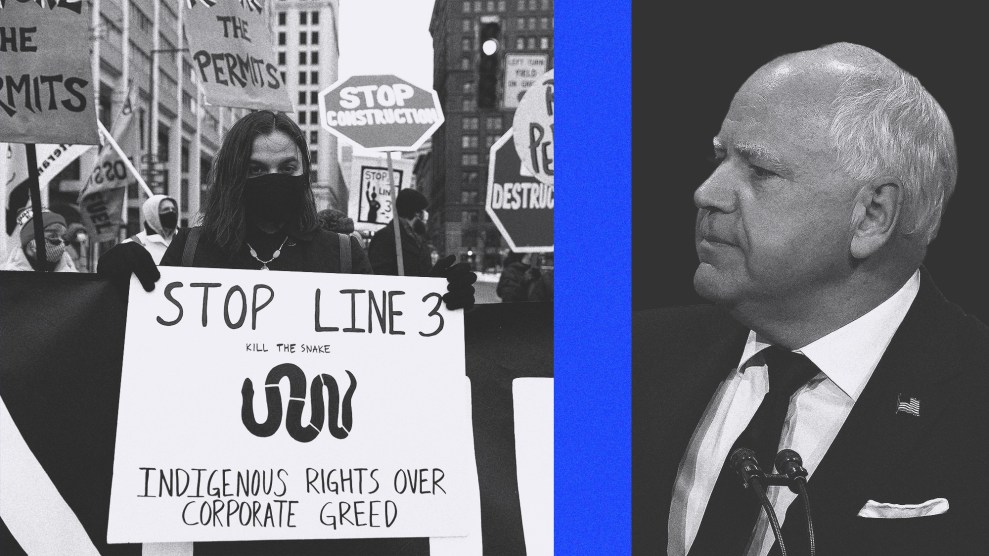

The independent counsel law was not renewed by Congress the following year, and the Justice Department now has a system under which the attorney general (or the deputy attorney general, should the attorney general be recused) appoints a special counsel in cases posing conflict-of-interest concerns. This is a step toward the process Kavanaugh advocated, though it lacks presidential involvement and Senate confirmation. This is how Mueller came to be selected special counsel by Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein. And if Kavanaugh were today to be consistent with the thinking underlying his 1998 proposal, he would support impeachment should Trump try to intervene in Mueller’s investigation or fire Mueller.

This question—should Trump be impeached if he blows up the Mueller investigation?—did not come up during Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings. But Democratic senators repeatedly voiced their concern that Kavanaugh has a history of being deferential to executive power.

Kavanaugh’s proposal for revamping the special prosecutor system—which would invest more power with the president—had a quaint quality. At the 1998 panel discussion, Kavanaugh said that a president should remain removed from the special prosecutor he appoints and oversees and that “Congress has to take responsibility for overseeing the conduct of the president.” He added, “When it comes to looking at the conduct of the president, it has to be the Congress. Congress has to get in this game and stop sitting on the sidelines.”

Perhaps Kavanaugh did not foresee a situation like the present one. After all, could Trump be counted on to appoint a special counsel to mount an investigation that might potentially target him—and to allow that probe to proceed freely? And the current Congress—controlled by members of the president’s own party—has shown a profound disinclination to investigate possible corruption or wrongdoing within the administration. In fact, several Republican House members have declared war on Mueller’s probe.

Kavanaugh’s proposal, if made today, would be justifiably criticized as naive. But his suggestion that presidential interference in a special counsel investigation warrants impeachment remains keenly relevant, given Trump’s extensive public efforts to discredit Mueller’s investigation and the reports of his private threats to fire Mueller. This certainly is one Kavanaugh opinion that his Republican champions do not want to cite.