Weingarten brandishes his oosik—a walrus penis bone. (Courtesy Gene Weingarten)

What would a hit man charge to take out Gene Weingarten?

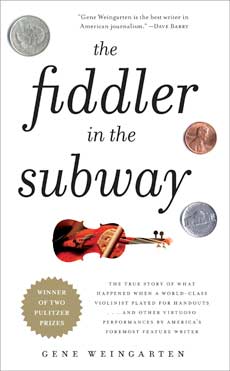

That’s likely the first question that will flit through the minds of ambitious young writers as they peruse The Fiddler in the Subway, a new greatest-hits collection of stories that originally appeared in the Washington Post and its Sunday magazine. The question is perfectly natural. All right, it’s not perfectly natural—it’s demented. My point is that very few living nonfiction writers could ever hope to match Weingarten’s mastery of pace, place, and character.

Regular Post readers have had two decades to envy Weingarten’s talents as a writer and editor. But I wasn’t aware of his charmed existence until the mid-aughts, when I read “The Peekaboo Paradox” and immediately began foisting it upon friends, family, colleagues, and pesky telemarketers. The story, which reappears here as “The Great Zucchini,” involves a guy who, despite being a total basket case, is DC’s top children’s entertainer—hauling in six figures for a two-day workweek headlining preschool birthday parties.

It turns out the Great Zucchini has a dark secret. (Which is, of course, no longer a secret.) The story was so naturally compelling that a chimp might have covered it passably. But here I shall invoke Louis Pasteur (think microbes and boiled milk), who famously said, “Chance favors the prepared mind.” In this case, chance favored the top-shelf wordsmith—it’s Weingarten’s deft touch peeling the zucchini that makes it a must-read.

“The Great Zucchini” was no fluke. Former Miami Herald humorist Dave Barry, who won a Pulitzer for commentary back in 1988, recalls teasing his “brilliant, funny, and clinically insane” editor—Weingarten—by reminding him that only one of the two had nabbed the big prize. But Weingarten eventually got the last laugh, nabbing two Pulitzers for feature writing.

He won his first one in 2008 for the title story of this collection, an ingenious bit of participatory journalism that appeared in the Post magazine as “Pearls Before Breakfast.” Delving into the meaning of beauty and the importance of artistic context, Weingarten convinced violinist Joshua Bell, one the world’s foremost classical musicians, to play the DC Metro incognito. Picture it: a guy for whom a “merely pretty good” concert-hall seat will run you $100 and up, busking for spare change on his $3.5 million Stradivarius. (Actually, you needn’t picture it: You can watch the abridged version here. Or read my own interview with Joshua Bell here.) It’s not hard to predict what’ll happen, but Weingarten plays his premise like a virtuoso.

In “The Ghost of the Hardy Boys,” our man sets out to find and kill—I’m not the only murderous bastard here—author Franklin W. Dixon after rediscovering his beloved childhood series and concluding that the books were pure drivel. I don’t want to give away the goods, but Weingarten does not find Dixon. He finds something else, and as in many of these stories, that something else is moving and unexpected—and/or hilarious.

This past April, Weingarten won his second Pulitzer for “Fatal Distraction,” a story friends had emailed me, but that I couldn’t bring myself to read until now. It’s about every parent’s worst nightmare: The soul-crushing realization that, somehow preoccupied, you have left your young child strapped in a car seat in a broiling parking lot. And that you have realized this too late. And that your life is, for all practical purposes, over. And this coming from a guy who has spent most of his career being funny. (Though semiretired, Weingarten still writes a Post humor column titled Below the Beltway.)

How and why would a notorious humorist pursue such a harrowing story? To find out, I would clearly have to shoot Weingarten myself. Questions, that is. Via email—his preferred method of execution:

Mother Jones: How does your experience as a humorist come in handy when tackling a decidedly unfunny topic—as in, say, “Fatal Distraction”?

Gene Weingarten: Many things have been written, including by me, linking humor and pain. The most famous and most widely misattributed quote is probably “comedy is tragedy plus time.” My favorite is this, by Dave Barry: “A sense of humor is a measurement of the extent to which you realize that we are trapped in a world almost totally devoid of reason. Laughter is how we express the anxiety we feel at this knowledge.” But that’s all background. Mostly, in my case, the humor part keeps me sane. If I spent all my hours writing things like “Fatal Distraction,” I’d become a brooding, erratic melancholic. I’d be Raskolnikov.

MJ: In the intro to “Pardon My French…,” wherein you travel to France early during the Iraq War to play the ugly American, you refer to your journalistic self as “the Machine”—an entity “rational, but soulless” that “thinks but does not feel.” It’s an emotional flak jacket any journalist can relate to. Do you find it difficult to switch from being professionally callous to personally caring? And do you suppose humor serves the same basic protective function?

GW: I report as a machine; I write as a person. That clear dichotomy softens the transition. As far as humor, absolutely a flak jacket. Humor is an escape, because you cannot think about your problems when you are trying to be funny; so, in essence, “being a humorist” gives you a valid excuse to hide from your pain: “Sorry, wife, I can’t think about what a selfish, sniveling shit I am just at this moment—I have to write.”

MJ: Your stories often start with a pretext, a la Joshua Bell. You’re on a quest, say, to discover the true “armpit of America,” or track down your first crush on Valentine’s Day—or you convince your editors to send you to the remotest place imaginable and report on it. How often does the resulting story jibe with your preconceived notions?

GW: With the single exception of Joshua Bell, I can’t recall a story that played out exactly as I’d expected it to. That’s one of the thrills of journalism—being surprised, and learning new stuff—but it also poses the biggest challenge to a writer’s character. The story you envision as you start out is always a great story; when the facts turn out to be different from, or more complex than, what you expected, your first reaction is always disappointment. That’s when you must fight the urge to bend the story to your preconceived notions. First, it’s dishonest. And second, in the end, the truth is always the best story.

A good example of this was “Fatal Distraction.” My goal from the outset was to humanize these poor parents; to present them in a sympathetic way. And then I met Lyn Balfour, who did not seem, at first, to be sympathetic at all. I disliked her. I had to talk myself down from jettisoning her in favor of a different central subject. And in the end, the complexity of her personality—her outward abrasiveness contrasted with a vulnerable core—made it a better story.

MJ: I laughed out loud a lot while reading this book. To what do you attribute your sense of humor? How much is innate, and how much shaped by childhood or other experiences? If I had to wager, I’d say you were the youngest sibling.

MJ: I laughed out loud a lot while reading this book. To what do you attribute your sense of humor? How much is innate, and how much shaped by childhood or other experiences? If I had to wager, I’d say you were the youngest sibling.

GW: Yep, the younger of two. I think I became funny because I grew up in the Bronx. I was small and weak and Jewish instead of large and fierce and Puerto Rican. You need something.

MJ: Please reflect briefly on your formative years.

GW: I grew up in the Southwest Bronx. Father an accountant, mother a schoolteacher. Brother was six years older, which explains why I gobbled crystal meth at 12, smoked hashish at 13, and was shooting smack at 17, which explains how I got Hepatitis C, which was the basis of my first book, which was a humor book about dying.

MJ: According to—uh—Wikipedia, you majored in psychology, but spent most of your time at the school paper. What were you writing then, and at what point did you know you wanted to do this for a living?

GW: I entered NYU intent on being a doctor, a career choice that got derailed for reasons pragmatic, emotional, and philosophical. Pragmatic: I flunked chemistry, probably the easiest course in the pre-med syllabus. Emotional: I walked into the college newspaper and discovered the elation delivered by a byline. Philosophical: I understood that with the combination of a doctor’s license and my attraction to opiates, I’d likely be dead at 30. I wound up quitting college with three credits to go, to hook up with a teenage Puerto Rican street gang. It led to this. I never went back to college.

MJ: To parrot the predictable-journalist question you asked Garry Trudeau: Where do you come up with your ideas? Do you have a process?

GW: Like all writers, my greatest inspiration, my ultimate muse, is a deadline.

MJ: Speaking of Trudeau, what qualities do you look for in a profile subject?

GW: Complexity, mostly. Complexity and connection to a larger picture. Back when I was an editor, and a writer suggested profiling somebody (say, Robert De Niro), I would always ask, okay, what will the story be about? And the writer would looked at me like I was deaf or daft, and say, “Uh, it will be about Robert De Niro.” And I would say, no, a name is not a story. You need to persuade me the story will examine something bigger about life. All stories are about The Meaning of Life, even profiles. Great example of this: Chris Jones’ recent Esquire piece on Roger Ebert.

MJ: What got you interested in the Great Zucchini?

GW: He had performed for children of friends of mine. They watched him slowly erode over time, and theorized he had a drug problem, and suggested I check him out. It was so much more interesting.

MJ: How much homework do you typically do before pitching a piece? Did your Post editors give you pretty much carte blanche?

GW: They do, now. I used to have to beg.

MJ: How do you know when it’s time to stop reporting and start writing?

GW: This is a really savvy question. I think you know the answer, because you asked the question. It is never time to stop reporting, but you have to make the call at some point. In my case, it’s usually when I know I have a good top and a good kicker, and feel relatively certain I’ve got enough to fill the spaces in between, and to answer all the really big questions.

MJ: Please share with us a bit about your writing process.

GW: Basically, I think the art or craft of longform narrative mostly boils down to figuring out internal kickers—how each section will end. Then you need to build the section to justify the kicker, to make it fair, and clear, and earned. I never start a section of the story without knowing how it will end. I also consciously try to shape the story as though it were a movie. I really try to think cinematically, because that’s how people read. They create a theater in their minds.

MJ: Which of the stories in this collection is your personal favorite (as a finished product)?

GW: “The Great Zucchini.” It was the perfect story—and when I say that, I don’t mean I did it perfectly. (I never do anything close to perfectly.) I mean that it was that rare story where it all panned out, and everything fit together. There was a mystery to solve, and as the layers peeled away, the mystery was…solved. In a really spectacular way.

MJ: Which one did you most enjoy reporting?

GW: The story on why the French hate us. Aside from the time I used petty cash to finance a visit to a whorehouse for a column, this was the biggest blast. I got to be a jackass, in Paris, in the interests of journalism and world peace.

MJ: Which was the most challenging for you—I don’t want to assume—and what made it so?

GW: “Fatal Distraction,” because of an intense emotional connection; the story kept me up nights, because I had almost done this to my own daughter. See this chat. I deal with this right at the top.

MJ: To end on a lighter note, I understand you’re a big-time dog person. Favorite and least-favorite breeds? Name of current canine and reason for name?

GW: I love all dogs except little yappy trembly things. Murphy is a purebred Plott hound, obtained from the pound, and her name was suggested by a reader. Wife liked it because of Murphy Brown. I liked it because of Murphy’s Law.