Molina volunteering as a paramedic at a protest in Nicaragua in May.Isaac Molina

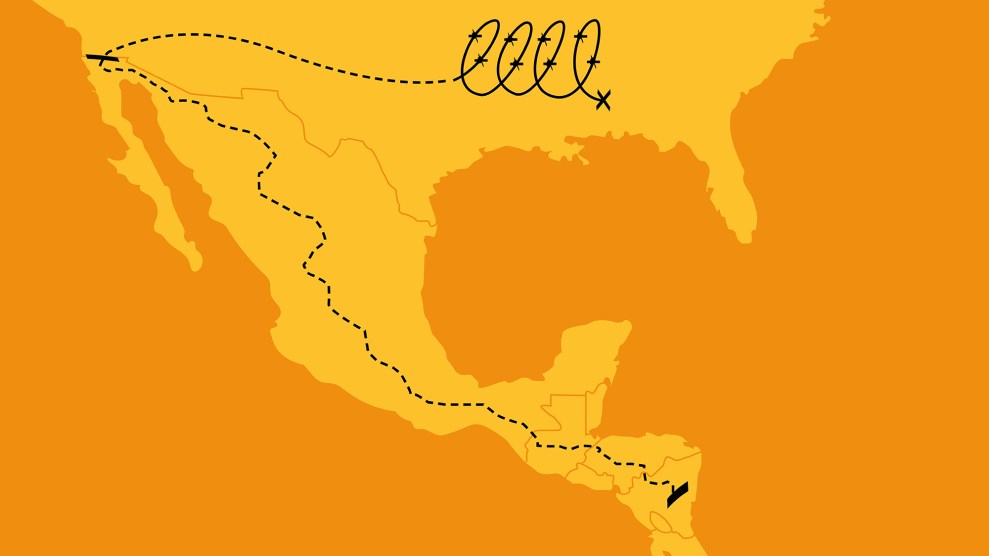

On Thursday night, just after nine o’clock, I received three text messages in three minutes. “He’s out,” an immigration attorney wrote. “ISAAC IS OUT,” a second lawyer exclaimed. Then came the last from his partner Fabiola, “Isaac ya esta en libertad,” she wrote in Spanish. Isaac is free. After more than 100 days in detention, Isaac Molina, a 27-year-old Nicaraguan doctor and asylum seeker, had been released from an immigration detention center in Georgia run by the private prison giant CoreCivic.

Molina’s story of attempting to enter the United States began in August, when he and his family had fled Managua after he was shot by police loyal to Nicaragua’s authoritarian president Daniel Ortega. As Mother Jones reported in February, Molina was targeted after providing medical assistance to anti-Ortega protestors:

On June 29, the police stopped Molina on his way to work. One officer told Molina to follow him and another climbed into his passenger seat. They drove to a spot near the national stadium and were soon met by a pickup truck carrying masked men. One of the men said it was time to “finish” things and shot Molina in the abdomen. That, apparently, had not been the plan. Another man interjected, “Not here.” Molina took advantage of the disagreement to make his escape, but the men shot at him again as he fled, striking him in the back.

Molina made a panicked call to a group of doctors, who took him to the hospital. A surgeon performed a laparotomy, a major incision to the abdomen, and discovered no damage to Molina’s organs. A doctor in Nicaragua, who requested anonymity due to fear of government retribution, told me that a full recovery from the operation takes a year.

In November, after leaving El Salvador for Mexico, Molina added his and his family’s names to a Tijuana-based list of people seeking asylum in the United States. He then returned to the southern state of Veracruz instead of staying in Tijuana, which was recently ranked the world’s most dangerous city outside of a war zone. We met in Tijuana late December just before he was allowed to cross over to San Diego. It had been four months since he fled, and he appeared on the verge of tears. He had an exceptionally well-documented asylum case, posed no threat to anyone, and had multiple family members with legal status in the United States with whom he could live. There was no reason for taxpayers to pay to detain him.

Molina on his way to the Mexican immigration van that took him to the United States.

Noah Lanard / Mother Jones

But the next time I heard from him was a month later, when Molina called from a CoreCivic prison in in rural Mississippi. His story, although it was all too real, sounded like a patchwork of multiple cases designed to highlight the injustices of the current immigration detention system. Their time in the United States began with the family separated for two- and-a-half days in the uncomfortably cold “hieleras,” iceboxes, where migrants are initially held. Fabiola’s 12-year-old son was detained separately. She was told he was too big to be held with her and her daughter.

Fabiola and the kids were then released to live with her sister and brother-in-law in Alabama, both of whom are doctors who could have provided medical attention to Molina as he recovered from his gunshot wounds. Molina spent more than a week in the hielera—far longer than the 72 hours that CBP policy generally allows—and then was transferred first to an Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention center in Arizona and then to a prison in Tallahatchie, Mississippi. Molina has a heart condition and was hospitalized in both states. ICE refused to let him out on parole. His biggest concern in Tallahatchie was about his ongoing recovery from a laparotomy, a major incision to the abdomen that was required to treat his gunshot wounds. As Mother Jones reported at the time:

Molina believes he has a hernia related to his laparotomy and says the inflammation around his gunshot wound is getting worse. Fabiola’s brother-in-law, a doctor in Birmingham, wrote to ICE last month, “Based on his recent medical history, including a gunshot wound to his abdomen, and his acute…chronic abdominal pain, I think it would be best for him to be seen by a general surgeon.” Molina submitted 14 requests for medical treatment in as many days. He says he never received a response. Molina told me Wednesday that he stopped submitting the requests last week after a guard began refusing to give him the required form.

CoreCivic disputed his account.

Molina was likely one of thousands asylum seekers moved from the border to Tallahatchie, where ICE started sending detainees after California stopped keeping prisoners there last year. ICE declined to say how many people it was holding at Tallahatchie in February, claiming that it tracks detainees by region but not by specific location. A spreadsheet that is now available on its website shows that on an average day the agency keeps nearly 1,000 people at the prison. All, or nearly all of them, are denied the chance to be released on parole, according to attorneys who have worked at the prison. The apparent violation of ICE’s own parole policy, which requires the agency to consider parole requests individually, forces asylum seekers to submit new requests once they are transferred to other detention centers, where they are often denied release again.

While Molina was in Mississippi, I wrote about CoreCivic’s long record of cutting services to maximize profits, citing its infamously isolated Stewart detention center in Lumpkin, Georgia, as an example:

The health services administrator at CoreCivic’s Stewart immigration detention center in rural Georgia said in 2016 that the facility had “chronic shortages of almost all medical staff positions.” A company supervisor described the facility as a “ticking bomb” because noncriminal detainees were often mistakenly housed with felons.

Molina wound up being transferred to Stewart later in February, where lawyers from the Southern Poverty Law Center took up the fight to get him out. They succeeded on Thursday, when ICE told Molina they were releasing him on parole. ICE does not explain why it approves some requests and not others.

Erin Argueta, an SPLC attorney at Stewart, went to the parking lot to wait for Molina when she found out he was being released. She knew it might be a while: ICE does not say what time people will actually walk out. He emerged, overwhelmed, about four hours later.

Molina was more fortunate than many of the nearly 50,000 immigrants detained by ICE on any given day. Most do not have a lawyer, let alone a team of them, working for them, and he got out quickly compared to others. “It’s terrible that despite his medical conditions, and strong support, and strong claim, and everything he had going for him he still was detained for almost four months,” Argueta says. “It’s also terrible that there are people that are detained for over a year, over two years, while their cases drag on.” Many of those detainees have medical conditions and families who can support them as well.

Molina after he was released from detention on Thursday night.

SPLC

Molina and I spoke briefly on Thursday night, the connection cutting in and out and as he and Argueta made their way through rural Georgia. He said he hoped to arrive in California on Friday to join his mother Fátima Rojas, a permanent US resident, and continue his asylum case. The dejection that sometimes came through in his voice while he was detained was gone. Meanwhile, Fabiola and her kids are still in Alabama fighting their case for asylum. Molina will have to figure out how to divide his time between them and his mom.

On Friday afternoon, Rojas called me and described her first conversation with her son after he was released. “Mamá, ya,” Rojas recalled him saying on Thursday. “Ya estoy afuera. Por fin.” Mom. I’m out. Finally.