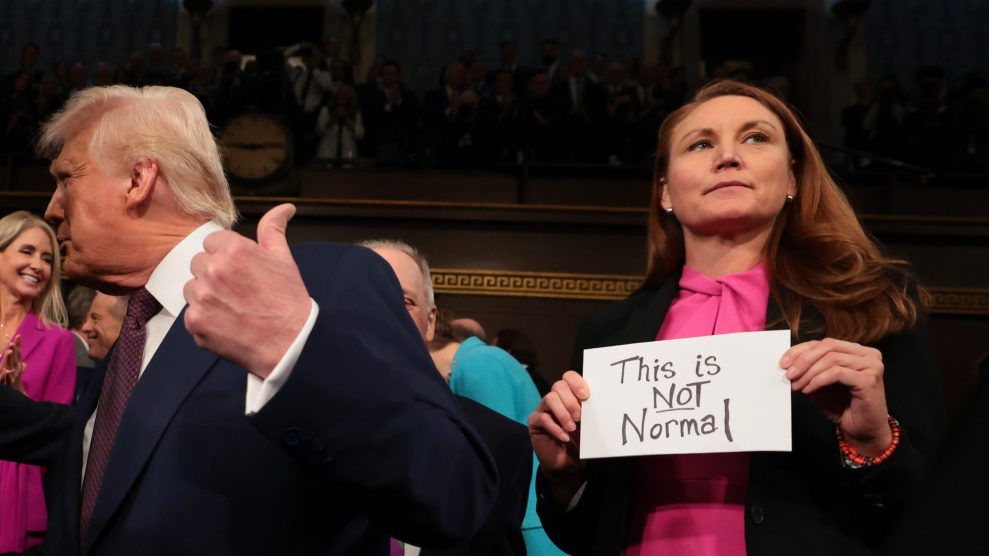

Nigel Farage after he was doused in milkshake during a campaign walkabout in Newcastle, England, on May 20, 2019.Tom Wilkinson/AP

The first recorded “milkshaking” took place May 2 in the English town of Warrington: 23-year-old Danyaal Mahmud was fed up with the words coming out of the mouth of Tommy Robinson, the white nationalist founder of the English Defence League, who was out campaigning for the European Parliament elections, and Mahmud dumped what was left of his milkshake on Robinson’s head. Robinson got in a few punches before they were broken up. A bystander yelled, “That’s what you get for being a fascist!”

With that, a spark was lit. Robinson was milkshaked again the next day. Anti-racist protesters then doused alt-right YouTube personality Carl Benjamin, who wound up getting covered in dessert four times in one week. Nigel Farage, the spiritual leader of the Brexit movement, was next. He was campaigning in Newcastle when a bystander lobbed a milkshake at the Brexit Party candidate, leading him to chastise his security detail as a “complete failure.” “You could have spotted that a mile away,” he said.

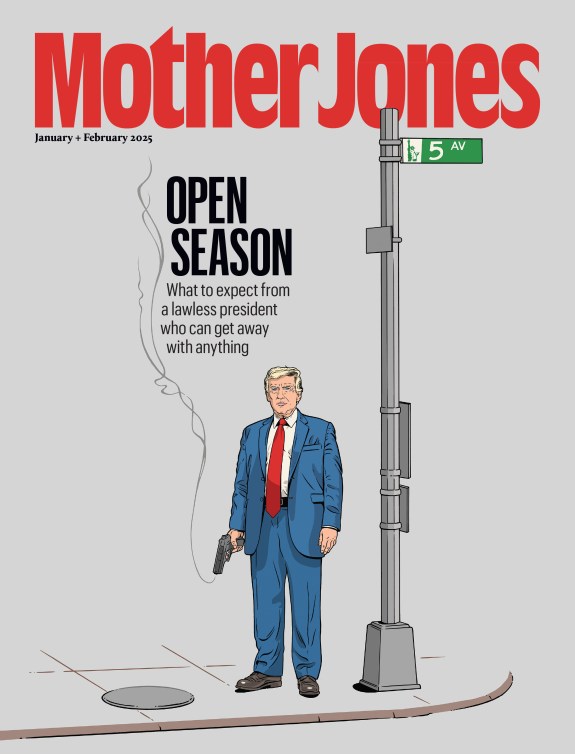

In May, milkshaking became so prevalent that British police forced a McDonald’s to stop selling the drinks near a Farage campaign stop, and the far right started describing it as “political violence.” The tactic finally made its American debut in early June—sort of. The target was Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-4chan), the GOP’s trollish rising star. Gaetz was leaving a town hall in Pensacola, Florida, when someone tossed what was initially believed to be a strawberry milkshake at him. (Reports later clarified it may have been Hawaiian Punch.)

In the annals of throwing stuff at assholes in politics, milkshaking is probably closest in spirit to the work of the Biotic Baking Brigade, a loose coalition of activists who liked to hurl pies at political foes such as Hilmar Kabas, Vienna’s neofascist Freedom Party leader; former San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown; and far-right political commentator Ann Coulter.

But in its viral spread, not to mention its “any weapon to hand” spirit of improvisation, milkshaking also reminded us of Muntadhar al-Zaidi, the Iraqi journalist who threw his shoes at George W. Bush and thus inspired a wave of copycat shoe protests around the world. The shoeing happened on December 14, 2008, more than five years into the war in Iraq. During a press conference in Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki’s palace, in Baghdad’s heavily fortified Green Zone, al-Zaidi stood up and shouted, “This is a goodbye kiss from the Iraqi people, you dog. This is from the widows, the orphans, and those who were killed in Iraq.” And then in quick succession, he sent his two shoes flying at then-President Bush’s face. Al-Zaidi’s aim was true, but so were Bush’s reflexes, and both shoes missed. It wasn’t long before al-Zaidi was tackled to the ground and badly beaten. He spent nine months in prison, where he has said he was tortured.

In the aftermath of the shoeing, al-Zaidi became something of a folk hero; one rich Saudi supposedly offered him $10 million for one of his shoes. He still lives in Iraq, where he recently ran an unsuccessful campaign for parliament, and he still considers himself an activist. “The only times I wouldn’t be protesting are if I’m sleeping or if I’m dead,” he told me recently.

I spoke with al-Zaidi to discuss the ethics and effectiveness of shoeing, pieing, Nazi-punching, and milkshaking, and what constitutes a step too far. Our conversation took place over the phone and later over email, with the help of a translator, Mariam Dwedar. It has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Why did you throw your shoes at George W. Bush?

George Bush lied to the people. He said the Iraqis would welcome him with flowers. And George Bush was saying the Iraqis were celebrating the American occupation forces that saved them from Saddam Hussein. And the world believed him. I wanted to say that no Iraqi would welcome the occupation with flowers. I wanted to show how my people were being killed by the bullets of the American occupation.

As journalists, we were witnessing dozens of people killed and assaulted, kidnapped from their homes and put in jails. Unfortunately, much of the media were working to further the American agenda. There were very few journalists communicating the needs and desires of the Iraqi people.

Did you have a plan? How did that day unfold for you?

I had been planning to do that for years. I was looking for a way to make a statement as powerful as what George Bush did in Iraq—but with the opposite meaning, flipping the idea that Iraqis would welcome him with flowers. How could I embarrass George Bush in front of his own people and tell them that he brought their sons and children to Iraq so they could kill?

I thought of this way, and I recorded a video before I went to throw the shoes on the off chance that I would be killed by the Secret Service or someone else. I didn’t want people to project meaning onto what I had done as something sectarian or overly political. I stated the reasons why I did it—that I was seeing so much of my country destroyed and people killed. It was for the love of my people and land, not to do with anything sectarian and not to do with any terrorist groups or militias.

How did you feel in that moment, when you threw the shoes?

I felt like my end was near. In Iraq we have a saying, “I said my goodbyes to the world.” I was a little bit nervous, but when I was finally able to throw them, I felt at ease. Later I felt it in my face and my nose and my teeth. It was painful because of the beatings I endured.

What is the symbolism of throwing shoes? Why shoes as opposed to anything else?

Throwing shoes at someone is considered an insult in Arab culture. Arabs are very welcoming and respectful to their guests, but those who we hate—who we hate to a great degree, or feel contempt against—we throw shoes at them.

When you really love someone or have feelings of love toward somebody, one of the sweetest things you can throw at them would be flowers. When you have contempt for someone, one of the worst things you can throw is shoes. Because he lied to the people, saying Iraqis would throw flowers at him, welcoming him, I wanted to show what the Iraqi people were actually feeling.

What were the consequences?

I was tortured and harassed. They broke my teeth and my nose—in the same room that George Bush was in. It was one of the worst beatings. I’ve never faced a harsher response than the beatings I was subjected to for that.

Was it worth it?

Even if I was killed on that day, the action would have still been worth it. It was worth more than the torture and beatings I was subjected to. I expected Bush’s bodyguards, who make themselves out to be like big supermen, I thought they would shoot me immediately.

And what kind of an impact do you think it had?

I can’t honestly tell you what the impact of it is. But it is the reaction of an Iraqi citizen and journalist who lived through the occupation, witnessed the occupation killing his people, and witnessed the world staying silent about what was happening in Iraq. It was a scream against a criminal. It was like a message sent in Morse code from someone far away from everyone else, saying to the world, “Save the Iraqi people from this crazy person.”

In America we’ve had the Biotic Baking Brigade, a loosely connected group of people who have thrown pies at politicians and controversial media figures. Now people are throwing milkshakes at far-right politicians in the UK. What do you think of all this?

Any method and anything you can do against these people to mock them, to humiliate them, is good—especially against any extremists, regardless of their religion, whether they’re terrorists, Nazis, anything like that.

Are you familiar with the debate about punching Nazis? It kicked off when the white nationalist Richard Spencer was punched during an interview.

It should be without harming people. It’s better to humiliate people like Nazis or extremists, but in ways that don’t physically harm them.

It looked like you really aimed to hit Bush with your shoes. How is that different from punching a white nationalist?

The Nazis deserve even worse than a shoe. They’re very racist. But when I threw the shoe, it was about insulting [Bush], and not to injure or kill. At the end of the day, it’s a shoe, and not a fist or punch.

So the point of these kinds of actions is that they should be made to humiliate people, something that’s funny, but the step too far is what, violence?

Yes, it has to be without violence.

As opposed to carrying a sign in a political rally or march, why does confronting a politician in their own personal space—with pies or milkshakes or shoes—make a bigger statement?

Corrupt politicians and extremist politicians have to know that they’re obligated to the people. So there is no safe space for them—other than their bedrooms.

Why is it so rare that people confront politicians in this way?

I think millions of people would probably want to do things like throw milkshakes on corrupt politicians, but not all of them have the courage to do so. Not many people are prepared to be jailed or tortured or face consequences for those types of actions. That’s why the people who have the bravery to do it are so few. Most people probably wish they could do something like that but they’re afraid.

Muntadhar_al-Zaidi in his campaign center in in southeastern Baghdad, on May 6, 2018.

Khalil Dawood/Xinhua via Zuma Wire

What do you think of the Donald Trump administration?

Trump is the worst president after George Bush. George Bush is No. 1, and Donald Trump is No. 2 in evil.

What about him or his policies do you object to?

Trump is extremely racist. He is a materialistic and opportunistic man. And he wants to involve the American people in a new war, or wars. His racist policies toward refugees and migrants, and the racist wall that he is building between the US and Mexico—these are all reasons for my opposition to his administration and his policies. The American people are kind and peace-loving, and it’s up to them to choose well and not be influenced by the media into choosing a bad president.

How should people protest Trump and his policies, whether it’s within the United States or abroad?

Cut off his businesses. Disable his companies. I think it has to be through economic means, because Trump loves money. [laughs]

Should they throw shoes at him?

Originally that was meant as a response to George Bush. But if people want to do that, they are free to do so. There’s no copyright on that act.

You’re a journalist, and in the United States, often no matter how bad or violent things get, the US media will sort of play along and just ask questions. One journalist, Jim Acosta, is considered controversial, and all he does is ask sharp-edged questions. Should journalists be doing more in your view?

I think this type of conversation usually only happens in countries in which there is a certain amount of safety and security, and it can’t necessarily be applied to countries in the Middle East. If there were American journalists and an Iraqi army came and occupied their country, and the Iraqi president came and occupied the White House and set up a press conference, do you think that same journalist would cover that in the same way?

Good question.

And even more I think the journalists there in America are brave because they try to take a stand against Bush and Trump. I really, strongly support the Washington Post.

Yeah, they’re good.

Please don’t cut out that part I said about the Washington Post.

Okay.

Promise me.

I promise you I won’t. But I can’t promise that my editor won’t cut it.

Okay.

You recently ran for parliament in Iraq. How did that go?

I ran for a parliamentary seat on a platform of holding the corrupt accountable, and returning to the Iraqi people the wealth stolen by politicians. It was a new approach, and just a step in a journey of a thousand miles. What caused this attempt to fail is the direct involvement of the American Embassy. And I’ve received information that they vetoed a win for Muntadhar al-Zaidi and meddled with the results—they and the parties that make up the electoral commission.

[“These allegations are patently false,” a State Department spokesman told Mother Jones.]

Are you still an activist?

Yes, of course. The only times I wouldn’t be protesting are if I’m sleeping or if I’m dead.

Dedication.

Or if I’m playing with my daughter.

You became very well known, almost instantly. How did your action affect or change your life?

In 2003, I was a student activist, and a part of the student union and human rights groups. I used to protest, but I was also a journalist at the same time. And, until now, I have continued my fight against dictators. What has changed is that, more than before, people have been paying attention to my warnings against dictators and the corrupt. My life has changed for the people, not for myself. I’m still a journalist. I live a very simple, normal life. My life has changed for the people: educating people, spreading culture, thought, and forgiveness between Iraqi, the protection of minorities and the vulnerable, and the displaced and others.

What is your advice for people who want to speak out against what they see as wrong?

My advice is to help the oppressed in every place, even if it’s just a word. It’s the world’s obligation to speak out against the corrupt, because you don’t want your silence to allow them to think that what they’re doing is right or okay.