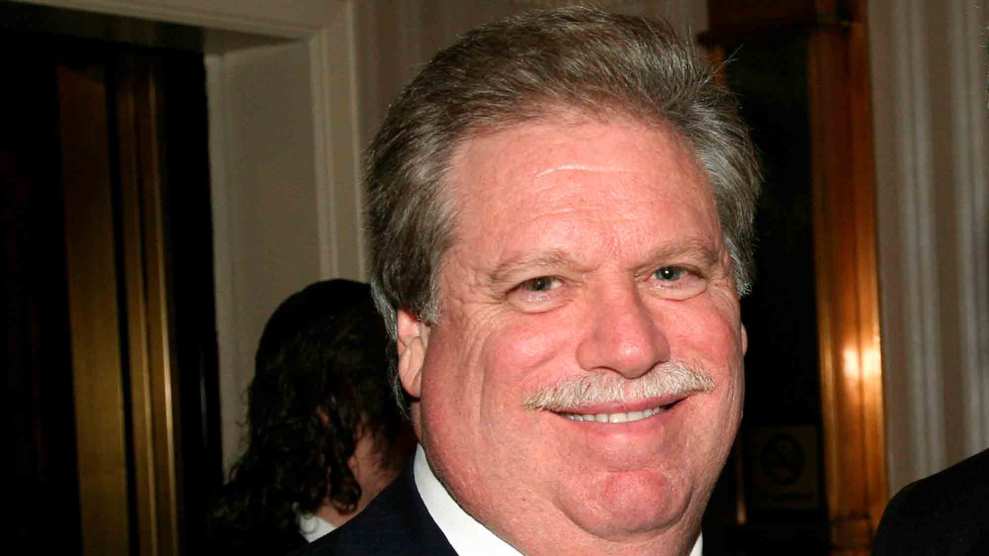

David Karp/AP

On Monday morning, the Associated Press reported that disgraced Trump fundraiser Elliott Broidy is being investigated by the US attorney in Brooklyn, New York, for possibly using Broidy’s ties to Donald Trump and the GOP to score big-money business deals with foreign leaders, including officials in Angola and Romania. The AP notes that “prosecutors appear to be investigating whether Broidy exploited his access to Trump for personal gain and violated the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which makes it illegal for U.S. citizens to offer foreign officials ‘anything of value’ to gain a business advantage. Things of value in this case could have been an invitation to the January 2017 inaugural events or access to Trump.” In response, Broidy’s attorneys maintained that he and his global security firm, Circinus, never reached a deal with the Romanian government and that the venture he did work out with Angola in 2016 was unrelated to Broidy’s contacts with Trump’s inauguration committee (which itself is reportedly under investigation).

Yet as Mother Jones reported last year, Broidy, who was a deputy finance chair of the Republican National Committee until it was revealed that he paid $1.6 million in hush money to his Playboy model mistress, did mix his business dealings in Africa with his political influence. Our December 2018 article opened this way:

In late 2016, as Donald Trump was readying to move into the White House, Elliott Broidy, then one of the Republican Party’s top fundraisers, was working on a deal to gain control of what a business partner called “billions of dollars in oil & gas, and mining assets” in Angola. And while he was trying to pull together this gigantic venture—as well as mounting another project to provide intelligence services to the Angolan government—Broidy used his clout to hook up top Angolan government officials with members of the US Congress and the Trump administration. It was a swampy endeavor involving old-fashioned political influence, a Beverly Hills activist and realtor, and a Nigerian American businessman who had been a close friend of Michael Jackson.

The story was in part based on emails that were hacked from Broidy’s personal accounts. (Broidy in 2018 sued Qatar, claiming Qatari officials orchestrated the hacks and a smear campaign because Broidy, a vigorous supporter of the Israeli government, was a vocal opponent of Qatar. In August, a federal judge dismissed the government of Qatar as a defendant in that case.) The emails detailed Broidy’s wheeling and dealing in Angola. As the Mother Jones article noted, Broidy and that Nigerian American businessman, Dolapo Asiru, were pursuing a deal to gain control of what Asiru called “billions of dollars in oil & gas, and mining assets” in Angola. At the same time, Broidy’s Circinus, under a $12 million contract, was creating an intelligence center for the Angolan government. The article reported:

As Broidy and Asiru were working with Angolans on the oil deal and the intelligence center, Broidy used his Republican Party connections to obtain invitations to Trump’s inauguration for two Angolan officials: João Manuel Gonçalves Lourenço, the defense minister, and André de Oliveira João Sango, the director of external intelligence. In a January 3, 2017, letter to the two men—on [Broidy’s] BCH Development Group letterhead—Broidy invited Sango and Lourenço to the inauguration, and he also included a copy of the contract for the Circinus project in Angola and asked them to sign and return the paperwork within six days. The letter was drafted by Asiru.

Lourenço and Sango accepted the invitation, and while they were in Washington for the inauguration, Broidy, according to the hacked emails, arranged for them to meet Republican members of Congress, including Sens. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) and Ron Johnson (R-Wis.). The meetings were set up by Aryeh Lightstone, a leading Orthodox Jewish rabbi and businessman who owned a stake in a Broidy company called Threat Deterrence Capital LLC. (Lightstone, a well-connected player in GOP circles, is now a senior adviser to Trump’s ambassador to Israel, David Friedman.) In one email, a Broidy aide informed Lightstone that the meetings would include Broidy, Asiru, Lourenço, and Sango, as well as Alberto Mendes of [Angolan oil company] Grupo Simples and Mario Gomes, another executive from the company. (The email did not explain why the two Angolan oil executives would be present.) Broidy appeared to be blending politics with his Angola business dealings: the intelligence center he was establishing for the government and the big oil endeavor he was pursuing.

The article also reported:

As Broidy was trying to do all this assorted business in Angola, he was using his political bonds to connect Lourenço, the Angolan defense minister, with the Trump White House. In a February 27, 2017, email to Asiru about the anti-corruption project, Broidy reported, “I will be at the White House meeting with VP Pence, CoS Priebus etc. tomorrow and can begin to set the wheels in motion for a meeting for the Defense Minister.”

And Broidy was willing to go all the way to the top. In this email, Broidy noted he would be visiting with “President Trump this weekend at Mira Largo [sic] (Friday) and on [casino owner and GOP fundraiser] Steve Wynn’s Yacht Aquarius on Saturday evening. I can also ask Trump for the meeting.” He noted it might be tough to arrange a meeting for the Angolan defense minister for this weekend, but added, “[W]e can certainly accomplish [it] this month predicated on next deal for BCH and immediate collection of balance.” The message seemed clear: If Angola paid what Broidy believed he was owed and moved ahead with a new project, he would use his political juice to arrange a face-to-face between Lourenço and Trump officials.

Lourenço is now the president of Angola. The piece concluded:

After helping the GOP regain the White House, Broidy has become a poster child for Trump-era corruption. He has generated headlines about multiple controversies—personal, political, and business. And there could be more Broidy stories to come. But the Angola episode illustrates how Broidy, having used the Trump campaign and victory to establish himself as a force within the Republican Party, did business—and indicates there is a public interest in learning the full story of how Broidy put his Trump and Republican connections to personal use.

The Associated Press reported that this latest probe of Broidy “followed a request last year by Democratic U.S. Sens. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut that the Justice Department investigate whether Broidy ‘used access to President Trump as a valuable enticement to foreign officials who may be in a position to advance Mr. Broidy’s business interests abroad.'” It added, “The Brooklyn probe appears to be distinct from an inquiry by Manhattan federal prosecutors into the inaugural committee’s record $107 million fundraising and whether foreigners unlawfully contributed.”

Asked about the AP story, Broidy’s attorney stated, “We will not comment on this kind of irresponsible speculation. We do not believe that any responsible journalist should repeat the AP’s claims unless they are able to independently verify them.”

There have been previous reports of Broidy being under federal investigation for assorted activities. But the AP story bolsters the possibility that Broidy’s controversial dealings—which stretch from collaborating on ventures with a now-jailed (on child pornography charges) George Nader, who was an adviser to the leaders of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, to being involved with a scheme to end a US investigation of a Malaysian financial scandal—could be more fully exposed and perhaps lead to other scandals tied to Trump World.