Mother Jones illustration; Getty

After Alabama lawmakers banned almost all abortions in May, with no exception for rape or incest, Jessica Stallings, a rape survivor from Fort Payne, was frustrated. But not for the reasons you might expect.

Stallings, a mother of two, actually supported the strict ban. She had been raped as a teen by her uncle, multiple times, and decided not to abort the resulting pregnancies. She loved her children, now teens themselves. But she was upset that it was still exceptionally easy for rapists in the state to get parental rights over the babies born from these assaults. A court had given her uncle permission to regularly visit her kids.

Alabama was one of just two states that didn’t have a law requiring courts to terminate the parental rights of convicted rapists in similar circumstances. So Stallings shared her story with the public and lawmakers, hoping to inspire change. And it seemed a fix was in the works: Rep. Will Dismukes, a young Republican who had just been elected to his first term, had prefiled a bill in February called Jessi’s law, or HB 48, that would allow courts to end a convicted rapist’s parental rights over a child born from the assault. Or so it seemed.

The law passed at the end of May, about two weeks after the abortion ban was enacted. But it didn’t do what Stallings’ supporters expected, and it went much further than the parental rights laws in most other states.

Between the time Dismukes introduced the bill and the time it passed, the language in the bill had been amended drastically. The bill now forced courts to take away parental rights from anyone who had ever been convicted of any first-degree rape, incest, or sodomy—even if no child was born from the assault, even if no child was victimized, and even if the assault had nothing to do with the person’s children.

“Let’s say a man is arrested, charged, and convicted of rape at 19 years of age, and 20 years on is now a 39-year-old man who has done his time, who has changed his life, who has had a child,” says Juliana Taylor, an attorney in Montgomery who specializes in family law and has studied the new legislation. “In the law, there’s no choice: The judge must remove the person’s parental rights,” even if it’s not in the best interest of his child, even if there’s every reason to believe the person is a good parent. It’s a “contradiction to the very purpose and goals of the juvenile court,” she says.

Under the law, a 16-year-old who has sex with a willing 13-year-old—a crime in Alabama, since the 13-year-old isn’t old enough to consent—could also lose parental rights decades later if he ever has a child, says Gar Blume, a longtime attorney in Tuscaloosa who has received national honors for his work on juvenile law. “It is so broad,” he says of the legislation, “that anybody ever convicted of a sex offense essentially is having their right to parenthood severely constrained, or there’s the potential for that to occur.” He described the law as “blatantly unconstitutional.”

Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle voted for the bill. It passed overwhelmingly in the House and unanimously in the Senate. But it’s unclear if lawmakers realized how sweeping the effects might be. “I’ve heard that maybe it was unintentionally made too broad,” Sen. Cam Ward, the chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, told me in July. The Democratic caucus is also a little concerned with how broad the bill is, added Amanda Brown, a legislative analyst for the caucus.

How did this happen? I was curious, because I had written about Stallings’ story and spoken previously with an advocate specializing in parental rights laws who was convinced, before the law passed, that the goal was more narrow, that lawmakers only wanted to stop convicted rapists from getting custody over children who were conceived from rape. So I began calling up Rep. Dismukes and any other lawmaker who would talk with me about how and why the bill had changed.

Tracking them down was an exercise in patience—for weeks I left messages, and most went unanswered. In the end, based on interviews with a couple of lawmakers, more attorneys, and the legislative analyst, it seems that the law was not originally proposed to help people like Stallings. And sloppy sentences inserted into the bill created confusion about what it would do. Even now, lawmakers, including the one who introduced the legislation, aren’t exactly sure how broad it is. And family law attorneys are worried about the consequences.

To understand what went down, it helps to go back to the beginning, where the first seeds of confusion were planted, on Valentine’s Day. That day, months before the legislature passed the abortion ban, Rep. Dismukes put forward one of his first-ever bills, Jessi’s law, in the state House. A 29-year-old from Prattville, Dismukes was a former college baseball player who became an ordained minister and worked for his family’s flooring company after a stroke squashed his dream of playing in the Major Leagues. He had been elected the previous November and sworn in a few months before introducing the bill, and he was the youngest lawmaker in the state.

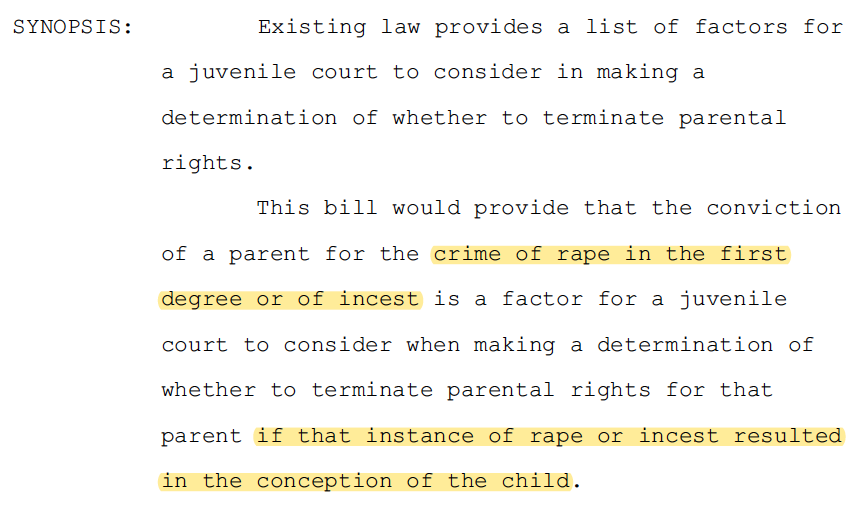

The bill, as he introduced it, seemed clear enough. A synopsis (copied below) stated that when a court was deciding whether to take away someone’s parental rights over a child, it could consider whether the person had been convicted “of rape in the first degree or of incest…if that instance of rape or incest resulted in the conception of the child.” Similar language was repeated in the bill text.

In other words, the bill seemed to suggest that if a man was found guilty of raping a woman and impregnating her, he could lose rights over the resulting baby. Forty-eight other states had similar laws, some requiring a conviction and some not, according to Analyn Megison, who helped pass legislation in Florida years ago after her rapist attempted to get custody of her child. Alabama had tried and failed to pass a bill like this in the past, added Rebecca Kiessling, a family law attorney in Michigan who has studied the issue nationally.

But Dismukes, it turns out, had something else in mind entirely. After I finally got him on the phone in July, he told me that when he introduced the bill, he wasn’t thinking about people like Stallings: He intended instead for courts to terminate parental rights in cases where a parent had raped their own child and the child had gotten pregnant. “The original was focused on raping your own children,” he said, something he reiterated multiple times. “It said you lost parental rights in a case of rape or incest when it involved the conception of a child.” (The bill, he added, was named after a woman called Jessi who was sexually assaulted by her father.)

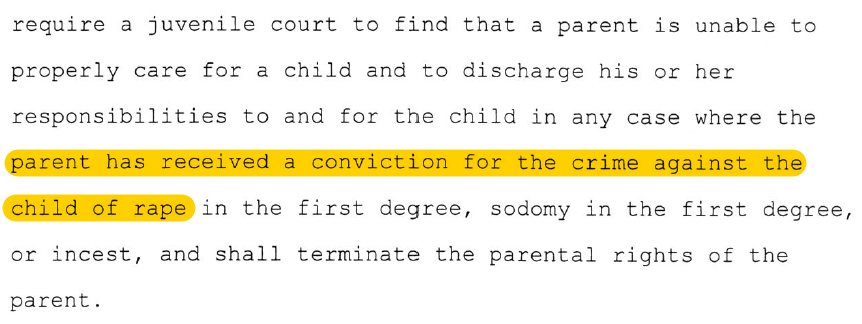

His proposal worried some lawmakers, who thought it was too specific in that it wouldn’t protect boys who were raped by a parent or girls who were raped but not impregnated. “Sen. Vivian Figures, who is a Democrat lady, said why don’t we make it stronger, and let’s remove ‘in the case of conception of a child,'” Dismukes recalled. He thought she had a point. So on May 28, the Senate amended the bill with that in mind. The House approved the changes the same day, and Gov. Kay Ivey allowed it to become law. The synopsis of the new legislation (below) also seemed clear, focusing on parents who raped their own children, as Dismukes intended:

But the synopsis—which is what many busy legislators focus on reading—is just a summary. It has absolutely no legislative effect, according to Blume, the juvenile law attorney. And the actual text of the bill didn’t match. It went much broader.

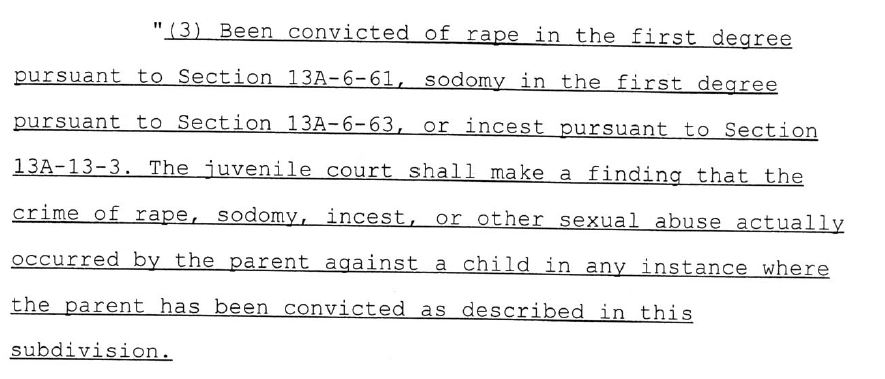

The first relevant passage of the bill that passed came on page five, in a section dealing with instances when a juvenile court can remove a child from a parent’s home quickly, without making any effort to keep the family together. It states, in the paragraph below, that this must happen if the parent has been convicted of first-degree rape, sodomy, or incest, regardless of who the victim was. “It doesn’t necessarily have to be the child itself that was the victim or the other parent that was the victim,” says Laurel Crawford, a former child custody attorney who leads the Montgomery Volunteer Lawyers Program. “It can be they raped, sodomized, or had an incestral relationship with anyone.” According to Blume, the second sentence of the passage strangely states that even if the parent in question actually assaulted an adult, the law requires the juvenile court to operate as though he or she really hurt a child. “It’s a very inartfully worded paragraph,” he says.

One key detail in the above text, according to Blume, Taylor, and Crawford, is the word “shall,” which, unlike terms such as “should” or “may” or “could,” removes all discretion from the judge to act differently. Another key phrase is “other sexual abuse,” something that could include lesser crimes like inappropriate touching.

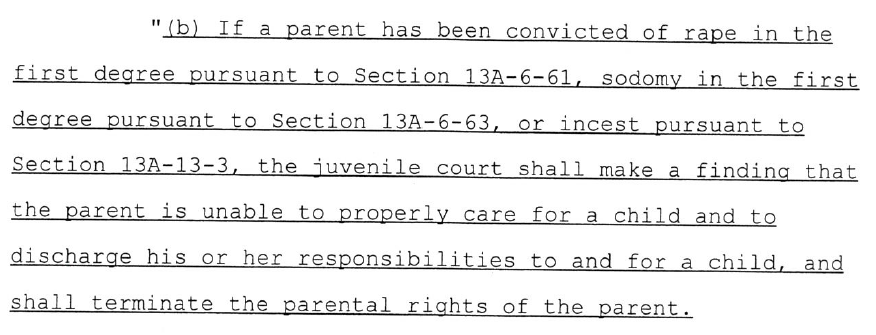

The next crucial passage (below) comes toward the end of the law, on page nine. It says a court “shall” terminate the parental rights of a parent who has been convicted of first-degree rape, incest, or sodomy, and again, it does not specify who the victim was. Nor does it include any time constraints. The crime could have occurred decades ago, before the individual was even a parent. The judge has no discretion to act differently. At least, that’s how Blume, Taylor, Crawford, and other attorneys they have spoken with interpret the wording.

This is also how Kiessling, the expert in Michigan, and Brown, the legislative analyst for the state’s Democratic caucus, interpret the law. Brown speculated that Democratic senators supported the measure because they were concerned about ramifications of the abortion restrictions that had just passed.

“Requiring [a court] to terminate the parental rights of someone without giving them an opportunity to be heard and without giving the discretion to the judge is not right, because there can be extenuating circumstances,” says Crawford. These extenuating circumstances happen more often than you might expect, adds Blume. He recalls representing a 17-year-old boy with intellectual disabilities who was accused of sexual abuse while riding the school bus after another kid, a 13-year-old girl with behavioral problems, asked if she could perform oral sex on him. Over the course of six months, Blume handled that case and another similar one, and he has heard of others. Any children who settle or admit to similar offenses could later lose parental rights.

“Did the legislature mean for this to happen this way?” Taylor says. “I have no idea. But that’s what it did. I don’t see a way around it.”

“We have very few lawyers in the legislature,” adds Blume.

It’s unclear if lawmakers understand what they’ve done. In July, when I asked Rep. Dismukes whether the law allows courts to terminate the parental rights of anyone convicted of first-degree rape, he said he wasn’t sure. “I don’t want to quote you wrong on it,” he said. “The way I understand it and interpret it is you lose the parental rights of the child you raped, and if there is a child that comes from that rape, those parental rights as well. Whether it extends past that point, that would be Bryan Taylor or David,” he added, referring me to speak with the governor’s legal adviser or a communications official, respectively. (The governor’s office said it couldn’t answer my questions and referred me back to Dismukes. The communications official never picked up his phone or responded to my messages.)

Dismukes added that if someone is convicted of raping a woman who then gets pregnant, the new law does allow courts to terminate the parental rights of the rapist over that child. But when I asked specifically what part of the legislation allowed for that, he again recommended I speak with other experts. “I drafted that bill two or three weeks before we even started session,” he said. “It’s kind of like a baby, you know: You look at it so much and you work on it so much that you know it frontward and backward, when all of a sudden it passes and then it changes and you get it for one day, you’re just sort of limited. I’m not trying to pawn you off to an attorney, but I’m not an attorney.”

“I think we should protect all mothers of circumstances of rape and make sure no one has some type of parental right after they rape somebody,” he added.

Hoping for more clarification, I called every member of the Senate Judiciary Committee. When I asked him if the law allowed courts to terminate parental rights of anyone convicted of first-degree rape, he also wasn’t sure off the top of his head. “I’d have to look back,” he said. “But I’ve heard the same thing, that maybe it was unintentionally too broad. There may have been some confusion there in the end.” When asked how I might determine whether the law was indeed that broad, Ward initially urged me to talk with a nonpartisan legislative aide who helped draft the law, but later said an aide would probably never agree to an interview. He added that he didn’t offer the amendment himself—that it was either offered by Dismukes or Sen. Clyde Chambliss (R). Ward also recalled Sen. Figures (D) urging amendments. “I just wasn’t involved in negotiations for that bill so I just can’t speak to it as well as they can,” he said.

When I called Chambliss’ office, a spokesperson declined to comment and told me to call John Rogers, a different communications official, who did not return any of my messages. When I tried to call back Chambliss’ office to explain Rogers wasn’t answering, the office did not pick up the phone or return any of my messages. When I called Sen. Figures’ office, a spokesperson said the senator was unavailable and would follow up with me. She never did, and her office did not pick up or respond to any of my subsequent messages. None of the other lawmakers I contacted ever responded to my messages. When I tried to call Dismukes back repeatedly, he never answered his cellphone and nobody picked up at his office. Both voicemails were full so I couldn’t leave a message. He never responded to my emails.

The real irony is that, while the law is incredibly broad, it won’t actually help Jessica Stallings, whose uncle had visitation rights over her children. Jessi’s law only allows courts to terminate parental rights if there has been a conviction of sexual abuse. Stallings’ uncle was never convicted of rape or incest, even though she says she was 15 and he was 22 when she got pregnant with his child. “It went to grand jury twice, and both times they said there was not enough evidence to convict him, even though we had DNA and court documents and birth certificates and medical records,” she told me earlier this year. “I had every piece of the puzzle I could possibly have, and they kept kicking it out.” Her uncle’s attorney declined to speak with Mother Jones about the case, citing attorney-client privilege.

Some lawmakers argue that this conviction requirement serves as a safeguard, to ensure men are not falsely accused and stripped of their parental rights without a guilty verdict in court. But family custody attorneys counter that the requirement limits who can be protected, since so many rapes are unreported or underprosecuted. Out of every 1,000 sexual assaults, on average only nine are referred to prosecutors, and only five lead to a felony conviction, according to a study by the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network. In June, according to the Washington Post, Sen. Figures said she planned to introduce new legislation that would allow people in Stallings’ situation to petition the courts to terminate the parental rights of their rapists, even without a conviction, as long as they have clear and convincing evidence a rape occurred—the standard required in roughly half of all states.

The Alabama law went into effect September 1. Lawmakers could revise it, to focus in more narrowly on situations like Stallings’, when they begin their next session, but that seems unlikely. “You’ve got to have a sponsor who’s willing to stand up in front of their fellow legislators and then have it reported back home that they were trying to make it harder to terminate the parental rights of sex abusers, and that doesn’t win anybody a whole lot of votes,” says Blume. If a parental rights case goes before a court, a lawyer can also argue the law is unconstitutional, “because parental rights are a fundamental right, and a due-process-protected right,” says Taylor, and under the new law, judges will have no discretion or ability to weigh the evidence. “Because it says ‘shall,'” says Blume, “all notions of due process fly out the window.”

In August, Dismukes announced that he plans to run for Congress, to fill the seat of Rep. Martha Roby, who will not seek reelection. “Our country is fighting a radicalized movement on the left that is threatening our freedoms, liberties and way of life,” Dismukes said in a press statement. “Republicans need a bold new conservative in Congress who isn’t afraid to stand up to the socialists on the left and the big-government politicians in our own party. I am someone who has proven, in my very short time in Montgomery, that I will do what is right for the taxpayers, regardless of party.”

“I think I have proven that I will look at an issue and study it and make the decision that’s best for my constituents,” he added.