Mother Jones Illustration; Getty

Dr. Anthony Back has built a career on delivering bad news. An oncologist and palliative care doctor in Seattle, Back has been teaching providers how to have tough conversations for the last eight years as part of an organization he co-founded to prepare physicians for what can be the toughest part of their jobs.

That group, VitalTalk, has long focused on Back’s own medical specialties, where terminal illnesses are most commonplace. But lately, his inbox has been overrun with doctors and nurses on the front lines of the coronavirus pandemic, asking a new kind of question: How should they tell their patients they can’t receive life-saving care because there isn’t enough of it?

“We are seeing this huge spike in interest, because clinicians are realizing that this big boulder is coming ahead of them and they’ve got to figure out what to do with it,” says Back. “One of the anxiety points for every clinician right now is rationing.”

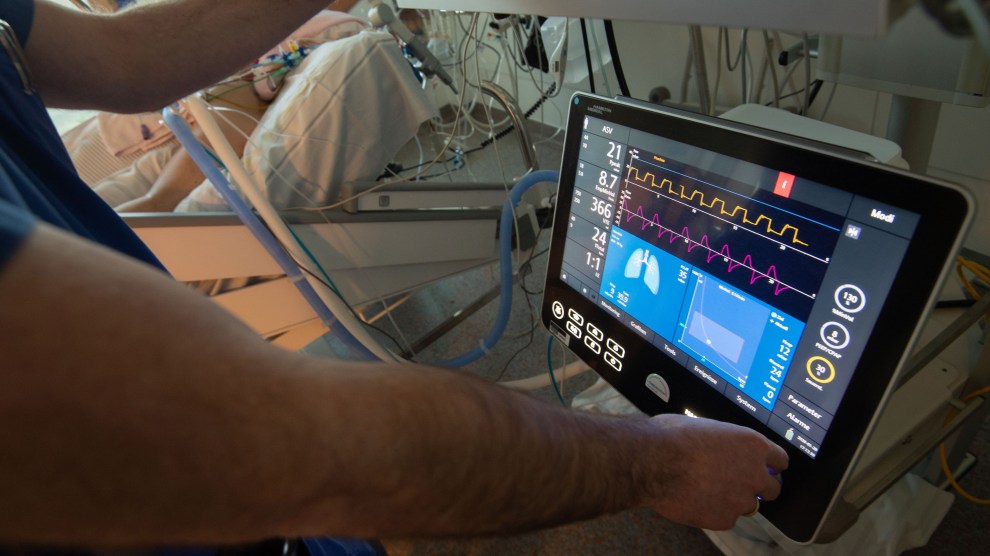

Of all the numbers on the coronavirus—more than 800,000 confirmed cases and 45,000 deaths in the United States (which are roughly doubling weekly), and 100,000 to 200,000 deaths considered a victory—perhaps the scariest are the figures on supply shortages. US hospitals have approximately 170,000 ventilators, and the American Hospital Association estimates that of the 96 million Americans who will come down with the coronavirus, 960,000 will require the support of ventilators.

Physicians are already seeing the potential shortages affect their work. Some hospitals are experimenting with having two patients share one ventilator; others are instituting Do Not Resuscitate policies for COVID-19 patients. Just a few weeks ago, the head of emergency medicine at NYU Langone Health reportedly emailed his colleagues to encourage them to begin thinking about triage, advising them to “think more critically about who we intubate” and assuring them that they had the organization’s support if they choose to “withhold futile intubations.”

Yet triaging—deciding who to treat, and who not to, when resources are scarce—is not often taught in medical schools. And although hospitals commonly have policies in place for surges of patients, the coronavirus complicates things because we’re still trying to pinpoint the best way to treat it.

“We aren’t starting literally from scratch, but this is a novel disease,” says Nancy Berlinger, a research scholar at the Hastings Center, a bioethics institute. “There weren’t off-the-shelf plans ready to go in the same way that [hospitals] know how they would respond to a mass shooting, or a flood.”

In 2015, a team of doctors, medical ethicists, public health experts, and lawyers drafted ventilator allocation guidelines for New York, where, even under typical circumstances, about 85 percent of hospital ventilators are in use at any given time. The document advises hospitals to bring in “triage committees” once resource shortages emerge, who decide which patients will get ventilators based on health data provided by physicians. First and foremost, these committees are told to consider survivability—the patients that look unlikely to live, even with medical intervention, are kept off ventilators, and the patients who seem likely to recover with the help of a ventilator get the highest priority. Each patient is supposed to be anonymized for the committee, so external factors like age, race, and celebrity don’t play a role in decision making.

The method is meant to meet public health standards of care—doing the most good for the greatest number of people—but it’s far from foolproof. “It’s not an objective criteria,” says Paul Edelson, who teaches clinical pediatrics at Columbia University and helped write New York’s guidelines. He says it’s difficult to predict survivability because there’s still so much we don’t know about the coronavirus. For example, it sometimes leads to pneumonia, which often responds well to mechanical ventilation; in other cases, patients develop acute respiratory distress syndrome, which isn’t necessarily helped by ventilators.

Outside of New York, there are differing plans on whom to prioritize if hospitals are overwhelmed. There is no national standard protocol, except for a recent directive from the Health and Human Services’ civil rights office not to categorically put elderly people and patients with disabilities at the back of the line. Complaints of such practices have been filed by disability rights groups in at least four states in recent weeks. In Alabama, for example, “mental retardation” is included in the list of exclusionary criteria in the case of a ventilator shortage.

Beyond estimating a patient’s chances of survival, medical ethicists across the country have spent years debating the most equitable approach to allocating scarce resources. Hospitals could use a randomized lottery system or allocate ventilators on a first-come, first-served basis. They could prioritize certain patients, such as health care workers (since they have increased exposure and increased need during a pandemic) or pregnant patients (since some argue they’d be saving two lives rather than just one). There’s also the issue of extubating patients: Is it ever acceptable to remove a ventilator if another patient with greater need arrives?

But each of these approaches comes with drawbacks. A lottery system may not be an efficient use of scare resources, and first-come, first-served may inadvertently privilege those with greater access to medical services, potentially leaving out rural or uninsured people. The other two options assign some lives more value than others based on non-medical factors, such as occupation and family, which could be a slippery slope to deeming a certain type of person unworthy of care.

“Some of these are observations about inequality, and some of these are about the practical conditions of an epidemic,” Berlinger says. The only hard and fast ethical rules of triage, at least to Berlinger, are that no groups should ever categorically be denied care, and individual doctors shouldn’t be forced to make these on their own.

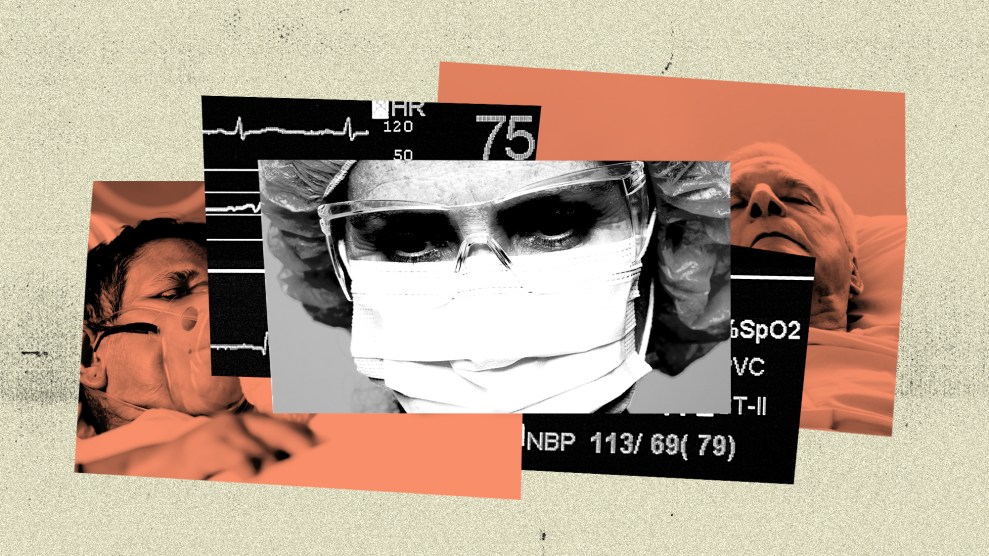

Traditionally, doctors are expected to advocate for the best care for all of their patients, so applying that ethos to a reality in which not all of their patients can be helped is difficult. “Nobody wants to be in that position,” Edelson says. It takes a toll on front-line medical workers’ mental health, having to relax their typical standards of care and instead consider: “What range of answers would be satisfactory? What would satisfy our need to be our need to be fair, to be equitable, to be honest?”

It’s a tough calculation.

“Doctors and nurses who are not normally involved in the care of dying patients are having to deal with a very high volume of death,” Berlinger says. She thinks front-line workers will be coping with the psychological effects of such circumstances long after the pandemic, even if they don’t have to make triage decisions. “Doctors, nurses, respiratory technicians, first responders all feel that this is something like going through combat together.”

Enter VitalTalk, which hopes to help medical workers answer those questions, especially in the wake of the coronavirus. The group has moved away from its typical eight-week online course, taught by some of its 650 faculty members, to 20-minute virtual seminars that doctors can squeeze in between shifts. The trainings are meant to improve communication for the benefit of the patient, but anecdotally, Back says clinicians have said they also help them cope with their own mental anguish.

The organization has posted free COVID-19-specific guidance online, which has been downloaded thousands of times in recent weeks by medical professionals all across the globe. The guidance offers sample language for delivering test results, explaining supply shortages, and notifying family members of a death. For explaining ventilator rationing, VitalTalk recommends this: “Across the city, every hospital is working together to try to use resources in a way that is fair for everyone. I realize that we don’t have enough. I wish we had more. Please understand that we are all working as hard as possible.”

To deliver the news of extubation: “I’m so sorry that her condition has gotten worse, even though we are doing everything. Because we are in an extraordinary time, we are following special guidelines that apply to everyone here. We cannot continue to provide critical care to patients who are not getting better. This means that we need to accept that she will die, and that we need to take her off the ventilator. I wish things were different.”