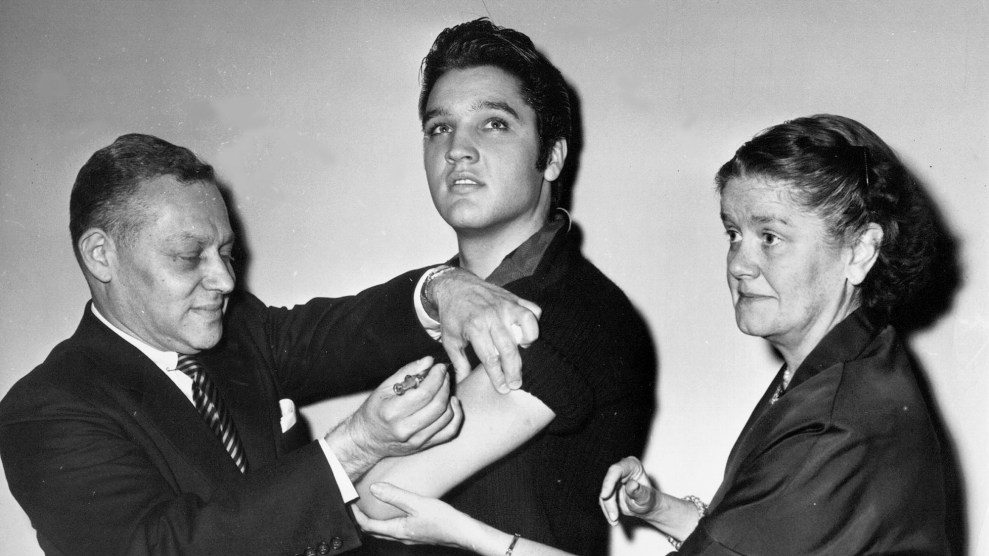

Elvis Presley receives the polio vaccine.AP

Let’s pretend it’s the year 2021. After rigorous clinical trials, the FDA confers a license of approval, and we finally have a safe and effective vaccine against the novel coronavirus. One problem is solved but a host of others follow. How can everyone be convinced that it’s safe and effective? How can enough be produced for the 7-and-a-half billion people on the planet who will need it? Even if there are sufficient supplies and a buy-in from those opposed to vaccinations, given how contagious the coronavirus is, how can there be mass inoculations without forcing people to congregate in ways that further spread the disease?

These are the questions with which public health officials, epidemiologists, and logistics companies are grappling. “It could be a great vaccine, but if you can’t get it to people it doesn’t count,” said Dr. Jon Abramson, a professor in the pediatrics department at the Wake Forest School of Medicine, a member of vaccine advisory groups at the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations (Gavi). He currently serves on two different coronavirus vaccine working groups. According to Abramson, more than 120 labs and companies worldwide are working toward creating a safe, effective vaccine.

In the most high-speed vaccine development program in human history, the Massachusetts-based biotech company Moderna jockeyed into first place in the last couple of weeks. Last Friday, the company announced it was starting Phase II clinical trials. This was after eight participants in a Phase I clinical trial for its mRNA vaccine showed antibodies comparable to patients who have recovered from COVID-19. Moderna’s stock prices soared, top executives sold off $30 million of stock, and its early successes were significant enough that even the administration’s most trusted voice during the pandemic, Dr. Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, expressed cautious optimism that we could have a vaccine sooner than expected. “It is conceivable, if we don’t run into things that are unanticipated setbacks, that we could have a vaccine that we could be beginning to deploy at the end of this calendar year, December 2020, or into January 2021,” he said in a May 22 interview on NPR’s Morning Edition.

Given the four phases involved in the development of any vaccine, there are a number of different points where the “unanticipated setbacks” that Fauci had warned about could derail the process. It might happen during research and development, or during the three phases of clinical trials required before any drug is made available to the public. Manufacturing large amounts will be difficult because vaccine materials are expensive and sensitive. Distributing the serum all over United States, not to mention all over the world, is a massive undertaking. Vaccines are biologic substances, vulnerable to heat, light, shock, and humidity. They need to be stored in special, industrial-sized pharmaceutical refrigerators at specific temperatures, usually between 2 and 8 degrees Celsius, for their entire journey from factory to hospital. And that’s all before a single dose is administered, and those logistics may be the most daunting of all.

The two most advanced vaccines in the running—Moderna’s and the Oxford vaccine—are entering Phase II of the clinical trials stage, in which the vaccine goes from being tested on a small group of subjects to being tested on thousands of subjects. After Phase II, there will be one more phase of trials, involving thousands of subjects to demonstrate its safety and efficacy. But clinical trials won’t be the most difficult part. Fauci said the speed with which vaccines are coming to market can strain the production process, disrupting the economic models for manufacturing and funding. To develop a vaccine as quickly as possible, the governments will be investing in and even paying companies to make doses of vaccines that might never work. “The risk is not to the patients,” said Fauci. “The risk is to the investment.” He means that massive sunk costs in the past have deterred pharmaceutical companies from manufacturing vaccines.

After a vaccine passes through the stringent clinical trials and the US Food and Drug Administration’s licensing process, it is up to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to give federal recommendations about how the vaccine should be administered. Dr. José Romero, the current chair of ACIP, is concerned about the challenges of producing enough vaccine for the entire US population, and the disparities that might result in its distribution. “A single vaccine manufacturer, up until this point, would not be able to produce enough vaccine for the entire population,” he said. “Will there be enough syringes, will there be enough vials to administer vaccine to millions of people in our country?”

Moreover, he notes, “It’s well known that the ravages of this infection have struck hard in minority groups. It’s shone a light on healthcare disparities in this country.”

Lacking any direction that could come from a coherent national policy, states have largely had to improvise their response throughout the pandemic. In much the same way that states have taken varying approaches to following the CDC’s recommendations on re-opening the economy, state health departments could adopt a variety of approaches in contracting with vaccine manufacturers and implementing a campaign. ACIP can only give recommendations. They have no authority to enforce them.

Producing mass quantities of whatever vaccine crosses the finish line first will also require producing mass quantities of needles, vials, disposal units, and protective equipment for health workers performing the inoculations. Abramson, who used to chair ACIP and is currently on multiple vaccine working groups, noted, “There will be supply issues, but they are already thinking about that. We learned our lesson the hard way with PPE.”

On April 2, Bill Gates, who has invested $300 million into fighting the coronavirus, went on The Daily Show. After making a fortune as the creator of Microsoft, Gates and his wife, Melinda, have invested billions of dollars into public health efforts through the Gates Foundation. The Foundation has led a global effort that has helped immunize more than 700 million kids and saved an estimated 6 million lives. He explained that the US government’s response to the coronavirus should be analogous to how the government prepares for war. “Every state is being forced to figure things out on their own. It’s very ad hoc,” said Gates. “It’s not like when a war comes, and we’ve done 20 simulations of various types of threats, and we’ve made sure that the training, communications, logistics, all those pieces fall into place very rapidly.”

He also shared his plan to prepare simulations for various types of vaccine manufacturing. With its previous success fighting diseases through vaccine alliances, his foundation is starting to build factories for seven of the potential vaccines in development. “Even though we’ll end up picking at most two of them, we’re going to fund factories for all seven,” he said. “It’ll be a few billion dollars we’ll waste on manufacturing for the constructs that don’t get picked.” Gates’ high visibility in the development of a coronavirus vaccine has made him the target of right-wing conspiracy theorists, despite the fact that his funding will likely be critical to getting massive amounts of the vaccine manufactured quickly—or maybe because of it.

Manufacturing sufficient amounts of the vaccine will do nothing until it gets to everyone across geographical and economic boundaries, in all ages and stages of life. Andrew Schadegg is president of Unitrans, a subsidiary of AIT Worldwide Logistics, a company that distributes products globally by air, land, and sea. Schadegg’s company is responsible for transporting vaccines and biologic drugs from factories to distribution centers, and then from distribution centers to administration sites, like pharmacies, hospitals, and doctors’ offices. “I’m not familiar with ever having a situation where that amount of product was needed to be manufactured and then shipped to all these different sites,” he said. “So that’s going to be a challenging one.”

Schadegg says that rolling out a coronavirus vaccine is logistically possible because the infrastructure is already in place. “You have distribution centers, you have temperature-controlled trucking. The technology is there to support this,” he said. “The global pharmaceutical companies have already been able to vaccinate large parts of the world in much more challenging environments.”

In normal times, about half of global air cargo is moved on passenger flights. But with most passenger flights canceled due to the pandemic, the entire global air freight system is under stress. Vaccine development is part of a global supply chain system. A turbulent trade environment makes it difficult to plan for vaccine deployment. “We’ve had a quasi-trade war with China for a long period of time and that’s been very disruptive to global supply chains,” said Schadegg. “Vaccines or pharmaceuticals are definitely involved in the global supply chain, so it’s key to not have a massive trade war break out.”

Matthew Watson, a senior analyst at Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Health Security and his colleagues have been paying particular attention to the vaccine’s distribution and administration. How will it be possible to administer a traditional injectable product to people who are not yet infected, who do not have immunity, and for whom waiting in long lines or congregating in doctors’ offices would be dangerous? With health care work forces already depleted, there might be a shortage of workers who can actually give the shot. That’s why Watson has been looking into alternative methods, like microneedle patches or tablets, that people might be able to receive in the mail and administer without the assistance of a health care professional. Plus, innovating how vaccines are administered could speed up the process during a future pandemic.

“It is notable that the two most successful eradication campaigns that we have on record are smallpox and polio,” Watson noted, “and they were administered not using a needle and syringe but using sort of an alternative route of administration.”

The poliovirus was a highly infectious disease that devastated populations around the world since the early 1910s, with especially bad outbreaks in cities like New York. It particularly afflicted children, killing and paralyzing tens of thousands. Finally, the polio vaccine, discovered and developed by Jonas Salk, was licensed in 1955, and a mass program began to vaccinate children and teenagers. This was the era before the Federal Vaccination Assistance Act of 1962 and no nationwide immunization program yet existed. The NYC Department of Health relied on massive publicity campaigns to convince its population to voluntarily get the vaccine.

And that’s why, on October 28, 1956, Elvis Presley appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show, a staple of Sunday night television from 1948 to 1971. Elvis played his guitar. He warbled his upbeat bluesy music and made eyes at the live audience. He swiveled his hips so seductively that the cameras only shot him from the waist up during future appearances because it was a “family show.” After he stopped singing, he was joined onstage by New York City Health Commissioner Leona Baumgartner and Assistant Commissioner Dr. Harold Fuerst. Baumgartner cupped the King’s left elbow as Fuerst plunged a needle into the same arm. And, with that, Elvis Presley was injected with the polio vaccine.

Photos of Elvis getting inoculated ran in all the major newspapers. Commissioner Baumgartner sent Elvis a letter after the event, thanking him “for letting us publicize your polio shot and for appealing to teenagers to get vaccinated.” Children and teenagers lined up and were vaccinated, first from a shot and later from a droplet of vaccine on a sugar cube. Today, polio is almost entirely eradicated worldwide. But the time when a straight-forward public awareness campaign could work in America is over. The climate of suspicion around vaccines has grown so thick, the distrust of authority runs so deep, the power of social media to amplify conspiracy theories is so potent, that it will require more than a simple celebrity photo to inspire the necessary confidence for vaccinating millions.

When it is finally created, it is likely there won’t be enough vaccine available, so epidemiologists and public health professionals are concerned about massive inequities between the inoculated haves and have-nots. If certain populations don’t have access to the vaccine, the global population remains at risk. On April 24, the WHO organized a virtual meeting in which leaders from around the world agreed to cooperate on a coronavirus vaccine and distribute it around the world. The United States notably was absent. So was India, a major manufacturer of vaccines, especially for developing countries. Public health officials worry that this could replicate what happened during the 2009 H1N1 flu pandemic, when developing countries only got small quantities of the vaccine after wealthy countries got the amount they wanted.

The coronavirus vaccine might shift resources away from other vaccines and biologic drugs. Last year, twice as many people in the Democratic Republic of Congo died of measles than Ebola, which demonstrates that as sophisticated as global pharmaceutical supply chains have become, we are still operating in a world of finite resources. Measles has not received the same attention or investment as Ebola, so the resources have been uneven. These disparities are especially stark in countries where it’s nearly impossible to keep vast amounts of biologic drugs in temperature-controlled facilities.

Challenges notwithstanding, we are likely to see the fastest, most sophisticated rollout of a vaccine campaign in human history. “From a scientific point of view, it’s incredible to think that from November until now, we’ve moved from identifying this virus to now developing a vaccine,” Romero said. “This is unheard of. In my lifetime I’ve seen the acceleration in the development of drugs and vaccines due to molecular virology and molecular biology. This is the fruit of that. It’s just phenomenal.”

Yet, even as the science of vaccine development has advanced at “warp speed,” the social climate around vaccination seems to have moved backward. Anti-vaccine groups on Facebook have already exploded with conspiracy-laden coronavirus content, like theories that the coronavirus does not exist and claims that social distancing protocols are tactics of the “police state.” Once a fringe group, the anti-vaccination movement has amassed real power—enough to potentially derail the success of a new vaccine campaign. Dr. Myron Levine, associate dean for Global Health, Vaccinology, and Infectious Diseases at the University of Maryland, has seen the impact of the anti-vaccine movement on vaccinology, a discipline he helped establish. “We have a big problem of folks saying they have a right to determine whether their child should receive vaccine,” he said. “A highly infectious virus like measles can come back.”

On a morning walk through Brooklyn, as I wandered past the shuttered shops and restaurants in a city where more than 16,737 people have died from COVID-19, I was thinking about how a vaccine could not come quickly enough. In an effort to learn even more, I typed “vaccine” into the search bar in Apple Podcasts and clicked on the first podcast that popped up—something called “The Vaccine Conversation.” After about 10 minutes of chitchat between Melissa and Dr. Bob, and numerous references to “data” and “the World Health Organization,” I realized that that they were calmly making the case that the dangers of the coronavirus had been grossly exaggerated. In my earbuds, Melissa explained that the economic shutdown is an overreaction and wondered why the government wasn’t describing “things you can do to boost your immune system” like increasing vitamin D or “reducing sugar.”

“The Vaccine Conversation” has been downloaded almost 400,000 times in over 90 countries, and it’s but one podcast within a vast media ecosystem of vaccine skepticism that is slowly shifting Americans’ attitudes. The antivaxx movement has already resulted in increasing cases of measles where they were once thought to have been eradicated. Two-fifths of adult Americans now express anti-vaccination policy attitudes due to perceived links to autism, and anti-vaxxers have been a vocal presence at protests to reopen the economy in states like California and Colorado. A recent Pew study shows that 27 percent of American adults would not get a coronavirus vaccine even though mass inoculation from an effective vaccine would be the surest way to end the crisis—for schools and businesses to reopen, and for people to be able to congregate and resume their normal lives without fear. As Watson had told me, “I do think that vaccine is ultimately the way that this gets resolved.”

During my walk, I came to realize that even in a best-case scenario, the rollout of a mass vaccine campaign will face unique challenges. Even if the logistics of manufacturing enough vaccine to curb a global pandemic are somehow resolved, a mature anti-vaccination movement can undermine its deployment and therefore its effectiveness. Whenever it finally appears, the coronavirus vaccine will test the limits of modern science in a post-truth world.