John Minchillo/AP

As Minneapolis burns and President Trump fans the flames with tweets so incendiary that Twitter slapped warning labels on them, reporters and editors have rightly called out his racist rhetoric, all the while using coded language of another kind.

From “rioters” to “looters,” newsrooms across the country are turning to headlines and tropes historically used to single out and vilify communities of color protesting police brutality. A CBS affiliate ran “Riots” in a headline about Minneapolis, as did Yahoo News and Reuters: “Rioters.” These words scarcely get used to describe largely white groups that destroy private and public property to make a point, as the Boston Tea Party did (a riot if ever there were), or to celebrate sports victories in the streets, as San Franciscans did when the Giants won in 2014.

What triggers the word “riot”: the nature and impact of the violence or the people behind it?

“Riot vs. rebellion/uprising is all in the eye of the beholder. This country was founded on acts of vandalism and property destruction,” Genetta Adams, The Root’s managing editor, tells me. “See the Boston Tea Party. This was a fight for ‘liberty’ and ‘freedom.’ Who decides what these acts are called? Unfortunately, today, all too often it’s all-white or majority-white newsrooms.”

A few years ago, on the 50th anniversary of the Detroit rebellion—set off by a brutal police raid on an after-hours drinking spot and the shooting death of Black men as the city burned for nearly a week—I wrote a Splinter piece arguing against defaulting to “riot” and for naming certain clashes what they are—uprising or rebellion:

“Riot” is a violent disturbance of the peace by a crowd, and “rebellion” [is] resistance to authority or control, with some conditions: If no peace was in place to begin with, the disturbance-of-peace requirement for riot isn’t met and the action may be a rebellion instead—if it’s aimed at demanding rights. “Riot” tells you next to nothing about cause, context, or goals. “Rebellion” hints at each: A rebellion is against something, for something, with emphasis on both subject and object.

“Riot” implies meaningless eruption, an isolated flare-up that ends when the violence stops, or a gust of empty destruction by “punks” or “thugs”—name your villain.

President Trump has named his: “THUGS.”

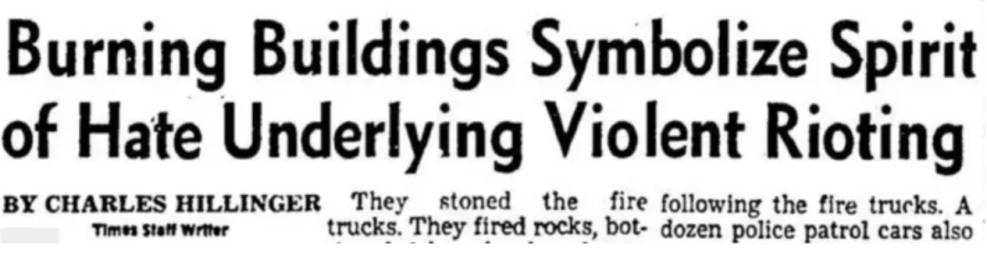

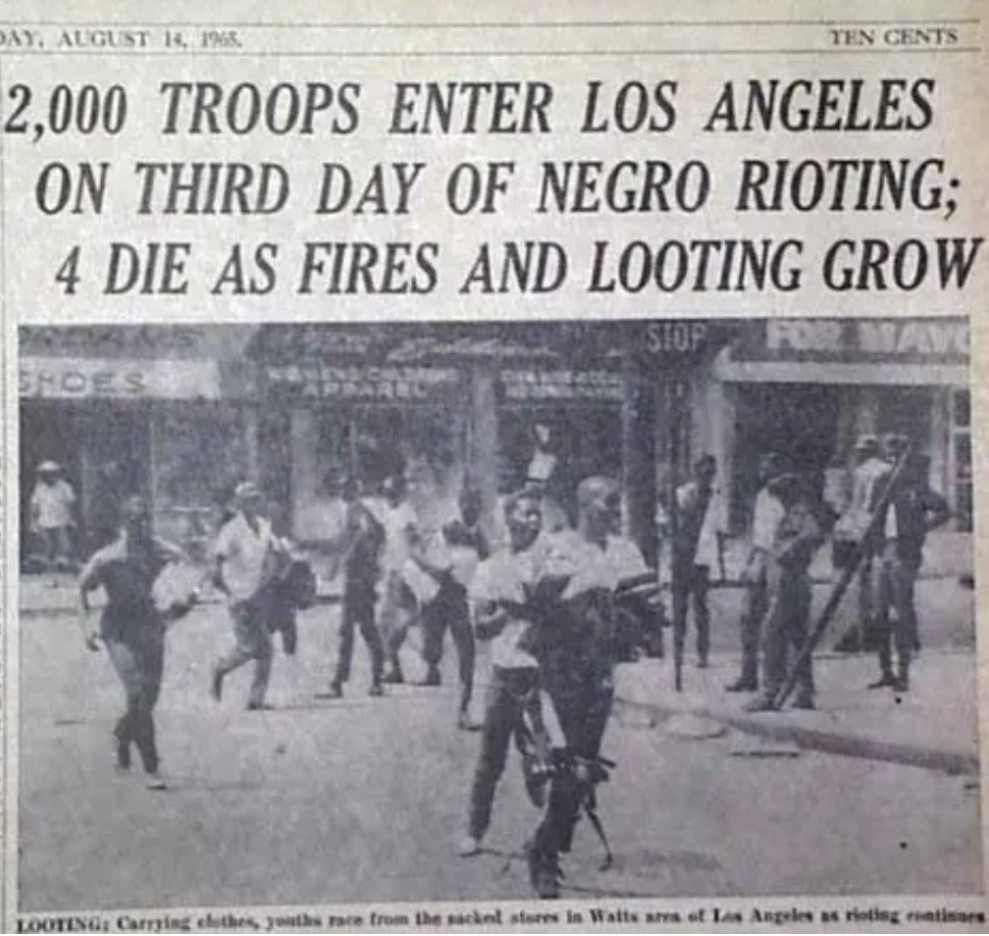

Take a tour of the “riot” archives:

July 29, 1964, Associated Press/La Crosse Tribune

August 13, 1965

August 14, 1965

August 14, 1965

November 25, 2014

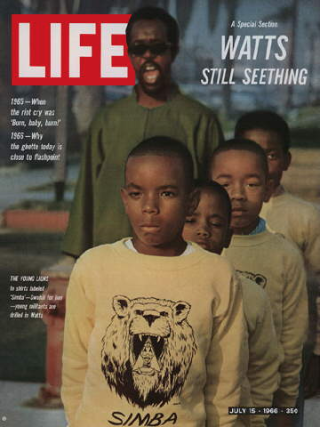

“Riot” isn’t the only word doing coded work in headlines. Labels like it are never far behind: “seething,” “simmering,” “boiling,” adjectives aimed at protesters of color under the surveillance, suspicion, and kneecaps of law enforcement:

July 15, 1966

Did Nat Turner “riot”? Did the enslaved Americans at Stono “riot”? I asked the same questions then and I’m still waiting for historians’ or linguists’ “yes,” but haven’t heard it. The sharpest objection to the distinction between “riot” and “violent protest” or “rebellion” readers made is that comparing Stono to Ferguson and Detroit is a historical anachronism, and that smashing storefronts itself doesn’t get you Turnerlike history. That’s definitionally and historically true. One reader wrote in: “The Stono Rebellion actually took the fight to slaveholders, burnt plantations, attempted an escape. Burning up stores in your own neighborhood is not a rebellion, it’s a riot.”

While the stage and setting are different, are the stakes, structures, and institutional impact so different? In many ways, very. But today’s overturned car signals a demand for an overturned system. Denounce or endorse it, but describe it right. All you get from “riot” is violence—the bottle thrown, window smashed, flame ignited. “Riot” takes any political project or purpose and reduces it to directionless rage. In Minneapolis, the fire this time is directed: at racist white police charged with murder, and entrenched power that authorizes it.

“Riot” doesn’t need a ban, which would be an overcorrection—there are riots, and some of what’s going on around the country includes pockets of them—but the word’s uneven and inaccurate use tells us how the media has headlined this history. And writing better headlines alone won’t solve it; yes, “violent protests” is a better fit, but just mouthing leftist language to sound liberal gets us nowhere. It makes us Amy Cooper, telling 911 there’s a threatening “African American” man and thinking that polite language absolves us of racism in 2020. Linguist John McWhorter and writer Coleman Hughes are exactly right about this aspect of language. Bayard Rustin was right about this too. If a style guide is all we look at, and not a collective mirror, all our work is still ahead.

The media’s project now is not only to use terms purposefully and precisely, but understand why.

What are your thoughts on the media coverage of Minneapolis? Weigh in below: