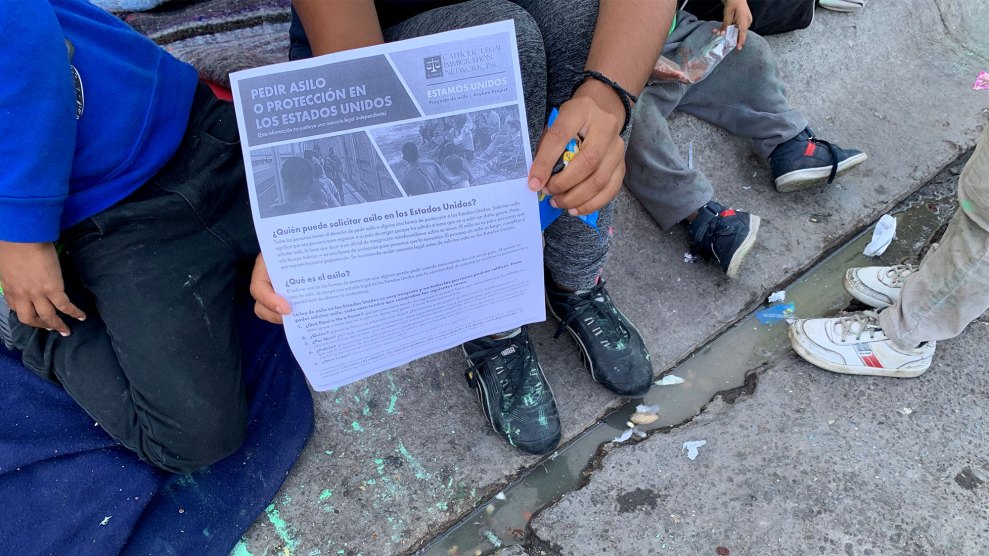

A woman and her sons sit in a makeshift refugee camp for asylum seekers near the border in Ciudad Juarez Mexico in late October 2019. Fernanda Echavarri / Mother Jones

President Joe Biden signed an executive order Tuesday that directs the Department of Homeland Security to “promptly review” one of the most impactful asylum policies of the Trump administration: the Migrant Protection Protocols, or Remain in Mexico, a program that has kept more than 60,000 vulnerable asylum seekers stuck in Mexican border towns for the better part of the last two years.

The executive order does not offer specifics on what to do with the tens of thousands of asylum seekers already in MPP, nor with those who didn’t get a fair shot at the process because of MPP in the past. But it does direct DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas to determine whether to “terminate or modify” MPP and consider rescinding the memo that set the policy in motion in January 2019. It also directs DHS to work with other departments and “promptly consider a phased strategy for the safe and orderly entry into the United States” for “those individuals who have been subjected to MPP for further processing of their asylum claims.”

Before signing this and two other executive orders on immigration Tuesday, Biden told reporters that he was aware there was “a lot of talk” about the number of executive orders he has signed since taking office two weeks ago. “I’m not making new law,” he said, “I’m eliminating bad policy.” He noted that he’s taking on issues the last president issued via executive order or memorandums that were “counterproductive to our national security, and counterproductive to who we are as a country, particularly in the area of immigration.”

The executive order on Creating a Comprehensive Regional Framework to Address the Causes of Migration also says the administration will work with its regional partners in Central America to address the root causes of migration and prevent more people from having to make the dangerous trek north and instead provide “protection and opportunities” to asylum seekers closer to home and provide refugees access to legal avenues to the United States.

The language in the executive order is a clear departure from how immigration was treated in the last four years: “Securing our borders does not require us to ignore the humanity of those who seek to cross them,” the executive order says. “The opposite is true.” On his first week in office, Biden directed DHS to stop all new enrollments in the program, though it didn’t make much of a difference to the current situation at the border: Since last March, the Trump administration had shut down the border to anyone seeking asylum, citing concerns with the spread of coronavirus. Biden has made no changes to that order yet but used this executive order to call for the CDC and DHS to review it.

“While these announcements are welcome and transformative news, the humanitarian crisis has not changed at the border, there is a tremendous amount of urgent work to fix a long failed immigration system,” said Alida Garcia, vice president of FWD, an immigrant rights group. “Fixing the Trump-manufactured humanitarian crisis begins with urgently providing clarity to the children and adults in MPP.”

MPP was first implemented on a small scale in late January 2019 in San Diego and then expanded across the the US-Mexico border. Attorneys with Human Rights First, represented one of the first cases to appear in court in March 2019 and have seen countless of cases of asylum seekers go through this process.

“We urge that any review of MPP be conducted quickly and focused on steps to swiftly transfer asylum seekers into safety in the United States,” said Eleanor Acer, senior director of refugee protection at Human Rights First. “Every day that this illegal policy remains in effect, families, children and adults seeking asylum are left stranded in places where they are at risk of kidnappings, assaults, and other violence.”

Human Rights First has tracked at more than 1,300 public reports of violent attacks against migrants subject to MPP. Immigrant rights groups have highlighted how this policy put already vulnerable migrant families in even riskier situations by sending them back to Mexican border cities to wait for months, often in makeshift camps that made them targets of the criminal organizations that control the region.

Human Rights First worked on a list of recommendations for the Biden administration, and in a document posted this month, they called for an end to MPP and a swift parole out of the program so migrants can live with family and friends in the United States while their asylum cases are pending. Human Rights First estimates there are about 20,000 people currently awaiting court under MPP—Cubans, Hondurans, Guatemalans, Venezuelans, and Nicaraguans among them. Many of them are families with young children, and many remain in danger.

The group also called on Biden to provide redress for people who were not provided a fair shot at presenting their claim for humanitarian protection. According to government data obtained by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, a research center at Syracuse University, more than 95 percent of the MPP cases that went through the immigration court system didn’t have legal representation, making it almost impossible to navigate a complicated process that required them to show up at the border, often in the middle of the night, so they could be bused to the nearest US immigration court for the day.

MPP has worn people down by dragging on the asylum seeking process to the point many give up. Salvadoran immigrant Juan Carlos Perla, his wife, and three young sons have been in MPP since they presented themselves at the port of entry in San Diego in early 2019, and today continue to struggle to survive in Tijuana waiting for their cases to be finalized. Almost two years later, Perla is now collecting trash in Tijuana and selling what he can to feed his family for the day.

Perla and his family went to court multiple times in 2019 and had their court dates pushed back for almost a year now because of the pandemic. The process has been so tough on them physically and emotionally, that at times he has wanted to give up his asylum case altogether. But he told me Tuesday that he’s glad to see that Biden is considering their dire circumstances so soon after taking office. “There is hope in seeing that they’ll start working on something for those of us who have been returned to Mexico,” he said. “And since we didn’t break any law, we knocked on the door legally, we followed every step in this for almost two years, so God willing, something good is headed our way.”

Like Perla, a Honduran man I met in a shelter in Ciudad Juarez in late 2019 was put in MPP with his wife and two children. He told me he was a police officer in Honduras who, after being extorted by a local gang, had to flee to the United States to apply for asylum. More than a year later, he says the family’s case went nowhere, so they left Juarez and moved to Tijuana to try to seek asylum again there. He messaged me last week desperately seeking answers on what Biden would do to allow them to go through the asylum process again, this time more fairly.

But Tuesday’s executive order offered little clarity regarding the next steps. Meanwhile, Perla and thousands of families will have to continue to wait and see exactly what Biden will do to fulfill his promise of a more “humane asylum system.”