The signature sound, pulse, and versatility of Roy Haynes, who turns 96 today, run as deep as the musicians who treasure him express here. For his birthday, I spoke with more than 20 musicians, each invoking a story that anchors Haynes in the pantheon of postwar jazz.

What emerges is not just reverence but a reflection of American rhythm over the 20th and 21st centuries. Haynes swung with Lester Young, Louis Armstrong, Sarah Vaughan, Charlie Parker, and John Coltrane, opening a new path by creating a language within a language. He expanded time instead of just marking it, freeing his hands to play above, around, and across the beat. He has become, as Wayne Shorter says, “a champion”—or, in the words of Mary Lou Williams, “the greatest drummer in the world.”

The interviews, conducted this week, have been edited and condensed. Hit the arrow at the right to return to the top.

Roy Haynes at 96

Brian Blade

Dee Dee Bridgewater

Terri Lyne Carrington

Marilyn Crispell

Andrew Cyrille

Billy Drummond

Tia Fuller

Marcus Gilmore

Tammy Hall

Billy Hart

Louis Hayes

Harmony Holiday

Jon Jang

Jerome Jennings

Oliver Lake

Branford Marsalis

Tiger Okoshi

Danilo Pérez

Reggie Quinerly

Wayne Shorter

Marcus Strickland

Nasheet Waits

Howard Wiley

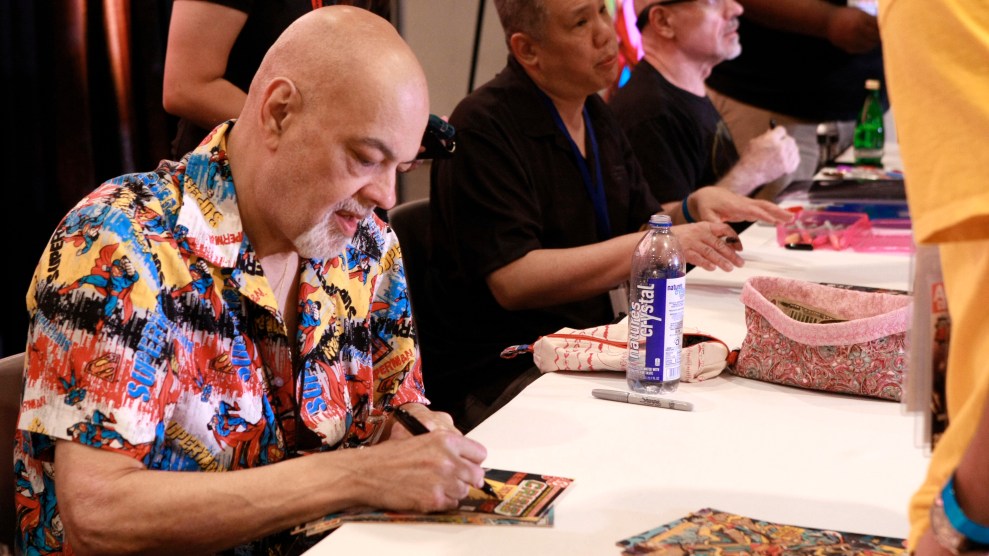

Roy Haynes in 2013

Anthony Barboza/Getty

Brian Blade, drummer:

Roy! Haynes! Drumming has always existed—someone’s always hit something and made a sound—but then comes Roy Haynes to spark imagination and wonder beyond rhythm and dancing and the pulse of life. Thank God for Roy in his 96th year. I’ve seen him several times, and when you do, you’re changed, your life is enriched. That’s what the music is about, and certainly what he’s been a vessel of his entire life. When you think of Thelonious Monk or Charlie Parker or Trane or Chick, you think Roy Haynes. He plays with levity and depth and so much joy. He’d have his left foot on the leg of the hi-hat stand, not even playing it. Like a dancer. Off the ground.

Dee Dee Bridgewater, vocalist:

There was one time Roy and McCoy were playing on a program, and Roy took a solo. I’ll never forget, he just stood up and started tapping. Oh my lord. I had never seen him tap. I knew he did, but what a moment. He taps like he plays drums. I love everything about Roy Haynes, and we both love cowboys. In the ’90s he was always wearing cowboy boots, so my idea was to get him to do a country-western album [laughs]. I remember we were honoring Max Roach at a tribute up in Harlem, and we were in the green room, and Roy had on some mean cowboy boots. I said, “We gotta do this album,” and he started singing, “You gotta know when to hold ’em, know when to fold ’em!”

When he turned 90, I went to see him at the Blue Note, and whenever I see him it feels like he’s just dancing behind the drums. If he insists on getting to the bandstand at 96, baby I’mma try and be there.

Terri Lyne Carrington, drummer and founder of the Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice:

I’m indebted to Roy. Words can’t express my gratitude for the inspiration he’s given me since I was a kid. I met Roy when I was very young—he would let me sit in on his kit and encourage me as a young girl who wanted to play the drums and had potential. The most important thing is people actually mentoring—mentoring moments. Roy is the hippest, the one I gravitated to when I started teaching, making sure my students check him out. My generation may cite Tony Williams and Jack DeJohnette, but I know for a fact that Jack’s biggest influences were Roy Haynes and Elvin Jones. I keep telling my students to go back to Roy, that they’re missing the whole boat if they don’t go to Roy and take a deep dive.

Roy has so much magic. I’d just humbly say thank you—and people bullshit and say stuff like this all the time, but I truly mean it—for providing so much inspiration. He knows I love him dearly. Roy’s way of making the drum set more fluid is unparalleled. He had and has the freedom to move away from 2 and 4, and make the drum set one sound. But you never miss the element of oomph. His playing makes me see other possibilities for myself.

Roy Haynes in 1999

Jack Vartoogian/Getty

Marilyn Crispell, pianist:

Everything that exists vibrates.

It’s been said that we live in a universe

Composed of music

Recurrent beats from our own heartbeats

To seemingly random or chaotic beats

Part of a pattern too large to see

Waves of a universal pulse.

Happy birthday, Roy.I played with Anthony Braxton for many years, and I was thinking of his concept of a pulse, like a wave and the phrases that fit it, with a crest and a valley. That larger picture has its own beat, and Roy plays that larger pattern.

Andrew Cyrille, drummer:

When you hear Roy and he’s playing with Thelonious Monk, you know it’s not Frankie Dunlop. You know it’s not Art Blakey. You know it’s not Ben Riley. You know it’s Roy Haynes. There’s a name given to Roy’s playing called Snap, Crackle, Pop. He has a way of assigning rhythm that’s different from other drummers, approaching those beats and the fractions within a bar that gives you a signature, and Roy’s always had a distinct one.

I remember talking to Max when I was a youngster—he was playing at Smalls Paradise—and after he played, I walked over and said, “Max, you played everything,” and he said, “No, I didn’t play everything. There’s a whole universe out there. If you want to find something for yourself, go out there.” That opened the door for me. Roy does too.

Billy Drummond, drummer:

One time I’m playing the Charlie Parker Festival. Max Roach is there, playing solo drums, and he sees Roy in the audience and pulls him onstage and the two of them are telling stories about their time with Charlie Parker. Which was already cool. Roy had just come from a car show where he’d won a trophy for his vintage Bricklin SV-1, which has gull wing doors, like the DeLorean from Back to the Future. After the festival, I’m on my way home and I come across Roy just sitting alone in his car, with the wings up, chilling with his trophy in the back and a cooler with ice and champagne. I say, “Hey, Mr. Haynes!” And he says, “Man, you want some champagne?” And we just hang out. I’m asking all these questions about Trane and Newk and Bud Powell. Just me and Roy on a side street in New York, drinking champagne. In his Bricklin! I got somebody walking by to take a picture of us. I have a few Roy Haynes stories, but encounters like that I’ll cherish for the rest of my life.

Every time I see Roy play, it’s a lesson in the mastery of what I’m trying to do. I make a beeline to see him at every opportunity. There’s a clip of him in the ’40s with Lester Young really breaking up time, playing syncopated rhythms that set the template for what came decades later. That’s why he’s the freshest, the hippest no matter what setting. And still is.

Tia Fuller, saxophonist:

Two years ago I got the chance to play with Roy for the Pixar film Soul, and he was an embodiment of history and extraordinary energy. He had more energy than all of us put together. Just to see him not only behind the drums, but I got video of him playing on piano—90-something years old. Here he is having played with all the greats, a legend, and still jumping into this music as optimistic as when he first picked up an instrument. That’s worth volumes.

Roy Haynes in 2008

Richard Ecclestone/Redferns/Getty

Marcus Gilmore, drummer:

He’s my grandfather first, but he’s also my hero in a lot of ways on the instrument. Just a blessing every day. He’s one of the most important musicians of the 20th and 21st centuries, that degree of wisdom and information, a learning experience. Not literally “How do you do this?” but being around him, his energy. We’ve always had a special connection. And it’s good you’re talking to Terri. She’s known him a very long time, coming up in Massachusetts together. My grandfather knew her grandfather, and Terri’s been in the community forever, came up in that community between grandpops and Jack DeJohnette.

Tammy Hall, pianist:

Mary Lou Williams comes to mind. She recorded an album with Roy Haynes in 1976 called A Grand Night for Swinging. She said, “He is the greatest drummer in the world.”

I used to be a little skeptical of that—not necessarily his ability, because he is great and one of the most innovative—but I remember first hearing her say that. I thought, “Really? The greatest?” But yes! I agree! Yes, he is the greatest drummer in the world.

I’m working on a piece right now about Mary Lou Williams called Convergence, where she and Nina Simone and Hazel Scott and Dorothy Donegan all meet up in Paris. It’s an oral tradition, an experiential one, and Roy is a mentor to many. I know one of his mentees, a young drummer who’s brilliant, Darrell Green. He’s learned a lot from Roy.

Billy Hart, drummer:

The last time I saw Roy was a year ago, and he still sounds fantastic in his 90s. I remember him at the Vanguard. When I was a teenager, a guy came up to me and said, “Have you checked out Roy? No? Well, you better get on it right away.” When I heard Roy’s recordings, there was my dream played out for me. I went up to Roy and said, “How you doing, Haynes?” And he looked at me and said, “How you doin’, Haynes?” [laughs] I mean, we’ve had Louis Armstrong, Baby Dodds, Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, and Roy Haynes. It just keeps going and it’s made an impact. God bless Roy.

Louis Hayes, drummer:

I’d like to give my regards to Roy’s family, such a magnificent family, especially his daughter and two sons and his grandson, Marcus. My respect and regards to all of them, a big part of Roy’s life. Family and community are very important to me, and Roy has been part of this history of what they call bebop. He was there with Charlie Parker, Monk, Dizzy. Happy birthday, Roy.

Harmony Holiday, poet, choreographer:

The first thing I think of is Roy’s Western style. I love how he brought this Black cowboy energy into jazz because no one else really did. That’s a big deal. He still rocks the Black cowboy, and I saw him perform with Jason Moran. I was a big Tony Williams fan, and I got to see Roy live at a festival in Harlem. Roy seemed super young—you couldn’t tell he was the oldest person onstage. I didn’t think about age at all. I just thought about him being this amazing drummer, and he’s backed up Sarah Vaughan.

Roy Haynes in 1993

Jack Vartoogian/Getty

Jon Jang, pianist:

When I was 17 and getting my feet wet in the music, in 1971, there were two inspirational recordings with Roy Haynes that turned my life around: The live recording of My Favorite Things with John Coltrane, McCoy Tyner, Roy Haynes, and Jimmy Garrison, and Chick Corea’s Now He Sings, Now He Sobs, with Roy and Miroslav Vitouš. 96-year-old Roy Haynes joins an unbelievable small group of musicians who keep on keepin’ on creating music at the highest level. Cellist Pablo Casals recorded the Bach Cello Suites in his early 90s. Verdi composed his last opera when he was 80 years old. Eubie Blake was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in his 90s.

Jerome Jennings, drummer:

First time I met Roy, I used to hang with Clark Terry. I used to take CT to hospital visits because a friend of mine asked me, and one night we went to hear Roy at the Vanguard. The fact that I was with CT, Roy was very nice and cool to me, and when I heard Roy play the snare, it felt good. Lot of people when you think Roy Haynes, you think his complexity, but just hearing him lay it down, put it right down the pipe, right down the pocket, that was amazing. He was in his 80s and just jumps up.

One of the first things Roy said to me was, “Do you know my grandson, Marcus Gilmore?” He was singing Marcus’ praises, rightfully so. Marcus is bad. Roy helped create the language for jazz drums, man—him and Max, Art Blakey, Roy Porter, stretching the possibilities. I wish Roy a happy 96th.

Oliver Lake, saxophonist:

I had the pleasure of seeing Roy at the Blue Note and was totally blown away. I was just in awe at how present he was, how he swung the band, lifted the band off the bandstand. He doesn’t age. That he’s 96 is incredible. I’ve performed with his son, Graham Haynes, and throughout my career I’ve been associated with very strong drummers. I just go with the feeling of the drums, the drummers who play from the heart and want to make a complete communication.

Branford Marsalis, saxophonist:

Roy is one of the greatest jazz drummers ever. Pretty much the greatest. I’d say the greatest, yes. I mean, Elvin’s a close second. They’re basically tied, but—in this bizarre quest we have for individuality and innovation, pedagogical competence goes right out the window. When you think about the fact that Roy played with Sarah Vaughan’s trio, which is a specific kind of discipline, and then with Charlie Parker, which is another, then Coltrane, then Monk! And Roy sounds totally different in all four settings.

Roy grew up in that dance era where intensity and the beat were major requirements, and because he did, the shit will always have exuberance, intensity, energy, joyousness. And if the conversation is the usual boring-ass jazz conversation about “singular imprint”—which to me is, you find the five things you do well and play the same shit on everybody else’s records—then no, but if you’re thinking about the level of versatility he has, the shit’s just astounding. It’s something to admire. With a lot of my colleagues, the understanding of jazz comes through harmonic understanding, not basic tap-your-foot impulse. The music has to reflect all of that—and Roy’s does.

Roy Haynes in 2012

Jack Vartoogian/Getty

Tiger Okoshi, trumpeter:

Happy, happy birthday to Roy. We recorded together with Gary Burton, and I first met Roy at the rehearsal. I thought I was just there to watch. After a few songs, Gary asks me to bring my trumpet and join Roy. I was so nervous, but I tried my best and then I wasn’t nervous. After that, Roy, Steve, and Gary hired me for the gig. Gary says, “We want you to play.” Roy’s snare stuff was unbelievably swinging.

The sound of Roy’s drums: If you know the Japanese taiko drummers, they’re feeling the vibration of the skin—they don’t hit it, they bounce it. That’s how I felt. Roy doesn’t need the cymbals like other drummers. His drums are like boom. Swinging so bad.

Like a Rolls-Royce. I felt I could play anything on top of it. Thank you so much, Roy.

Danilo Pérez, pianist:

How I met Roy: I was in Barbados playing a festival, and a friend of mine and friend of Roy’s went to this club to jam, and I was drinking my glass of wine, so I went over my limit and I was on the happy side. Three hours went by and all of a sudden this hi-hat from heaven joins us. I look and there’s this man with a huge hat and nice boots. I didn’t recognize him, so I’m thinking, “My God, this guy’s incredible, I gotta get him to New York, get him a gig!” I said to him, “Sir, can you give me your phone number? You’ll take New York by storm. What’s your name?” He goes, “My name is Roy Haynes.” I almost fell off my chair.

That night, he took me around Barbados to eat fried fish, and that’s the first time he asked me to play with his quartet. We had that mentorship. One time we’re on a bus listening to Dear Old Stockholm he did with Trane. I’ll never forget how emotional Roy got listening to it. I carry that moment in my heart deeply. He’s cooking with some beautiful colors. And Roy was crucial for connecting me with my history of jazz in Panama. The first person who hired Roy was Luis Russell. Panama has a long history of jazz greats, and Roy was the first to hip me to that.

Reggie Quinerly, drummer:

One time I was at Port Authority at 4 in the morning, taking a train, and who do I see? There’s a short diminutive man in a cowboy hat. I walked up to him and said, “I know who you are” [laughs]. He was nice and cordial, told me he’d been partying all night and was taking the train back to Queens. Just the giddiness I had seeing Roy Haynes. It cannot be overstated how much he means to the music. First time I remember seeing him, he was playing in my hometown of Houston. What struck me was his life force and energy radiating from the drums, hitting me in my chest. That’s the vibe, and that stuff goes on the recordings. To me he plays life.

Wayne Shorter, saxophonist:

Hey Roy, happy birthday man. I’ll never forget the time we had at Slugs. Yeah man you were a champion and still are. You’re always gonna be a champion to me. You know? We love you man.

Roy Haynes in 2005

Schellekens/Redferns/Getty

Marcus Strickland, saxophonist:

A story I love to tell: We’re at a festival in Boston, and after we played we got into a limo, and the limo driver was blasting a Missy Elliott song. Roy knew all the lyrics—every single lyric. I didn’t know the lyrics. That shows me, man, this cat has never ceased to absorb what’s around him. He’s a force, always bringing fire. The first time I saw Roy was at the Vanguard. Russell Malone put out word that Roy was looking for a new saxophonist, and the first thing I notice is Roy’s boots. I’m used to drummers being all up in the hi-hat, but his foot was just chilling on the hi-hat stand donning those boots. And his ride cymbal was so strong he didn’t need the crutch of the hi-hat. Right then and there, it dawned on me how he changed the music.

Nasheet Waits, drummer:

My first introduction to Roy was through my father, Freddie Waits, who had a good relationship with Roy, the way you see old friends interact with jokes and hugs and admiration. I grew up in Greenwich Village and I’d tag along. Mr. Haynes, thank you for blessing us with your presence. You’ve been an inspiration for me and my father. I remember the first time I consciously “stole” something from Roy as a drummer. [laughs] I was in my 20s at the Vanguard. I was studying Roy, and for a week after, I was trying to sound like him, and people were like, “You sound like Roy—you sound like you were listening to Roy all week.” That’s exactly what I was doing. That’s the highest compliment—for a minute. I was like, “You’re right, I did see him last week, and this is All. His. Shit. Right. Here.” [laughs]

Howard Wiley, saxophonist:

First of all, anybody who’s in the lineage of the music so long and playing at a high level, everybody talks about Tony and Elvin and Philly Jo, but when you talk about their associations, you’re talking Roy Haynes. He’s on Dear Old Stockholm with Coltrane. What Roy is playing is so thick. It’s a thing he has and he makes whatever band he’s in. Roy Haynes all day. You talk about the Bud Powell tribute band? Roy. Haynes. All. Day. What I like about these cats, man, the OGs, they’d play the same equipment and sound so different. Roy put out this album that nobody messes with: Praise.

I was playing this gig with Amiri and Amina Baraka at the Malcolm X Jazz Festival with Marcus Shelby, and Amina was like, “Play this song,” and I’m like, “I’m shaky on the bridge,” and when you tell an old-school sister you don’t know something right before you go onstage, you get that look: It’s a very particular Motherfucker, are you serious? You done got me out here? I know that look, but I’m like, “Here’s this Roy Haynes song I really like and I think you’re gonna dig it too. It’s called ‘After Sunrise.’” And we play that. When I tell you I got the biggest hug and kiss from Amina after, and she’s tough, my man. Roy’s music has such a universal love.

First time I met Roy was at a conference. I introduce myself, we start talking. I’mma wear the OGs out, so I’m talking to him for an hour, and how you play all that shit in some cowboy boots? He’s wearing snakeskin pants and cowboy boots killing the drums. The joy he embodies. All praise is due, and happy birthday. This time last year he was scheduled to play Blue Note at 95 and I’m like, this motherfucker is 95 and playing the Blue Note. That’s the dude you wanna be—the drums and the spirit.

Send birthday notes to recharge@motherjones.com.