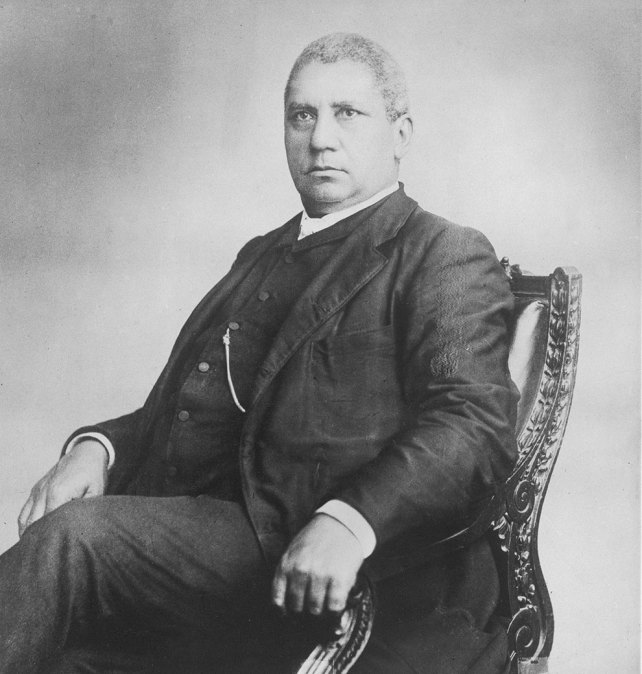

On September 3, 1868, Henry McNeal Turner rose to speak in the Georgia House of Representatives to fight for his political survival. He was one of 33 new Black state legislators elected that year in Georgia, a revolutionary change in the South after 250 years of slavery. Eight hundred thousand new Black voters had been registered across the region, and the share of Black male Southerners who were eligible to vote skyrocketed from 0.5 percent in 1866 to 80.5 percent two years later.

These Black legislators had helped to write a new state constitution guaranteeing voting rights for former slaves and leading Georgia back into the Union. Yet just two months after the 14th Amendment granted full citizenship rights to Black Americans, Georgia’s white-dominated legislature introduced a bill to expel the Black lawmakers, arguing that the state’s constitution protected their right to vote but not to hold office. “You bring both Congress and the Republican Party into odium in this state,” said Joseph E. Brown, who had served as governor during the Confederacy years, when “you confer upon the Negroes the right to hold office…in their present condition.”

Turner was shocked. Born free in South Carolina, he’d been appointed by Abraham Lincoln as the first Black chaplain in the Union Army. After the war, he settled in Macon, Georgia’s fifth-largest city, where he was elected to the legislature. As a gesture of goodwill, he’d pushed to restore voting rights to ex-Confederates. But now white members of the legislature—both Democrats and Republicans—were turning on their Black colleagues.

Turner’s passionate speech would become a rallying cry for the civil rights movement 100 years later. “Am I a man?” he asked. “If I am such, I claim the rights of a man. Am I not a man because I happen to be of a darker hue than honorable gentlemen around me?”

Henry McNeal Turner’s “I Claim the Rights of a Man” speech became a rallying cry of the civil rights era.

Time Life/Getty

But his pleas went unheeded. The legislature voted to expel the Black lawmakers, who weren’t even allowed to participate in the vote. “The sacred rights of my race,” said Turner, were “destroyed at one blow.” Soon he was getting death threats from the Ku Klux Klan. “We should neither be seized with astonishment or regret” if he were to be lynched, editorialized the Weekly Sun of Columbus, Georgia. Two weeks later, one of the ousted Black legislators, Philip Joiner, led a march to the small town of Camilla in southwest Georgia, where white residents opened fire, killing a dozen or more of the mostly Black marchers.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

And so Reconstruction all but ended in Georgia almost as soon as it began. Outraged Republicans in Washington attempted to reinstate it, putting the state back under military rule, purging ex-Confederates from the legislature, and giving Black members their seats back. But in the 1870 election, Georgia’s white majority united to reclaim the state and vote out the Black members, backed up by KKK violence that kept many Black people from the polls. “There is not language in the vocabulary of hell strong enough to portray the outrages that have been perpetrated,” Turner wrote to Massachusetts Sen. Charles Sumner. Five years after the war ended, ex-Confederates had retaken Georgia. “The Southern whites will never consent to the government of the Negro,” said Democratic US Sen. Benjamin Hill. “Never!” Georgia became a blueprint for how white supremacy would be restored throughout the South.

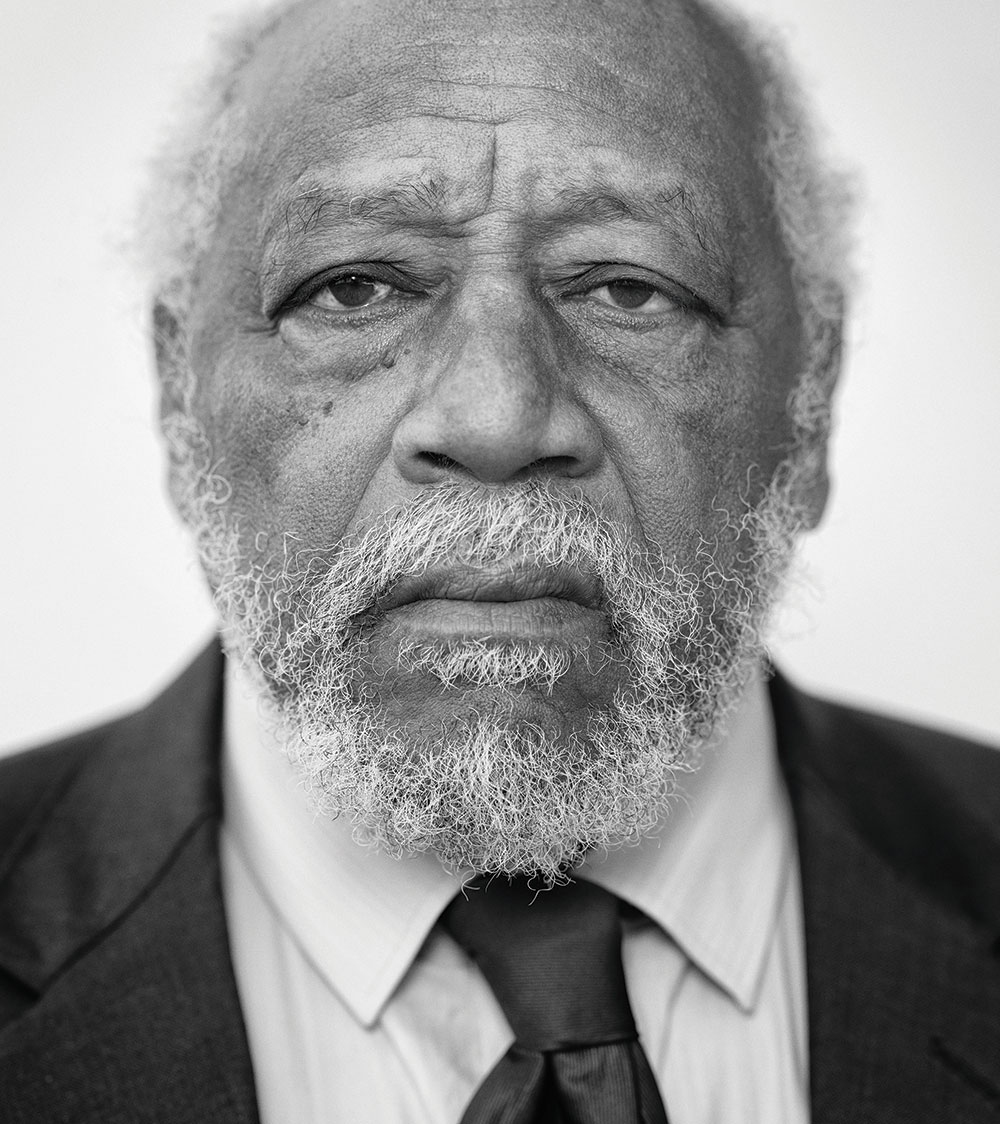

One hundred and fifty years later, another Georgia legislator representing Macon rose to defend the rights Turner had fought for. Like Turner, Democratic state Sen. David Lucas is an African Methodist Episcopal minister. In 1974, at just 24, he became the first Black member of the legislature to represent Macon since Reconstruction—a product of the second Reconstruction, of the 1960s, when the country passed civil rights laws, including the Voting Rights Act, to restore the squandered promise of the first. With his Super Fly suit and Honda 750 motorcycle, he stood out among the good ol’ boys in the state Capitol.

On February 23, 2021, Lucas, now 71, took to the Senate podium to oppose a new voter-ID requirement for mail-in ballots introduced by Georgia Republicans. In 2005, Republicans had specifically exempted mail-in ballots from the state’s voter-ID law, believing that more rural and elderly voters would be the ones casting them. But now they were changing the rules after the Black share of mail-in voters increased by 8 points in 2020 and the white share fell by 13 points. The measure was one of 50 anti-voting bills they’d introduced after the state went blue in November and Donald Trump tried to overturn the election results by falsely alleging a massive conspiracy to rig the vote.

Lucas, the in-house historian of Georgia’s Legislative Black Caucus, said the bill “reminds me of the election of 1876.” He told the story of the disputed presidential contest that put Rutherford B. Hayes in the White House on the condition that he would withdraw federal troops from the South, officially ending Reconstruction. “When they pulled out the federal troops,” said Lucas, “that’s when we had Jim Crow and folks got lynched.”

This history was personal for Lucas. When he was 13 and playing four square with friends, the police picked him up and falsely accused him of throwing a rock through a white driver’s windshield. They took him to a convenience store, where the driver got in the back of the police car, placed a gun to his head, “and told me he’d kill me,” Lucas said. Later, as a student at Tuskegee University, he worked on the campaigns of the first Black legislators elected in Alabama since Reconstruction, and worked with a Black professor of political science to register Black voters in the area. As he canvassed small-town dusty roads, white men in pickup trucks would drive by with shotguns and ask him, “Why are you registering folks to vote?”

After 45 years in office, he told his colleagues emotionally, he couldn’t believe he still had to defend his right to vote. What should have been the country’s most fundamental principle remained the most contested. “I will not go home and tell those folks who voted that I took away the right for you to vote,” Lucas vowed on the Senate floor.

A month later, Georgia Republicans passed a sweeping rewrite of the state’s election laws—rolling back access to mail-in ballots, limiting drop boxes, making it possible for right-wing groups to challenge voter eligibility, and boosting the heavily gerrymandered legislature’s power over election administration. Across the country, nearly 400 bills were introduced in the first five months of 2021 to limit voting access, the largest number of voting restrictions proposed at one time since the end of Reconstruction.

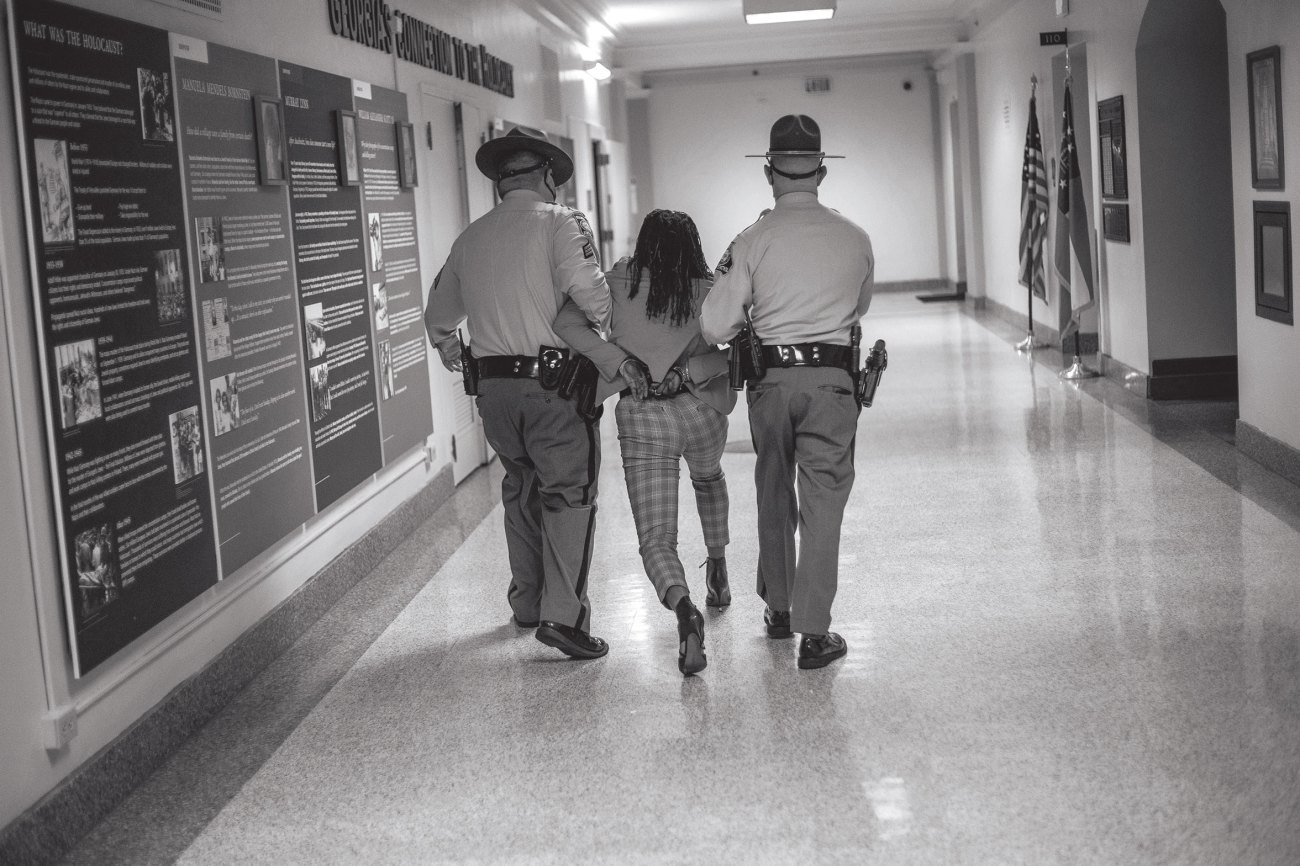

Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp signed the state’s voting bill alongside six white male Republicans, under a painting of a slave plantation. When Park Cannon, a young Black Democratic state representative from Atlanta, knocked on the governor’s door demanding to see the signing, Georgia state police arrested her and dragged her from the Capitol, charging her with two felonies (soon dropped)—a scene that harked back to the brutal crackdowns against 20th-century civil rights activists. “If you don’t like being called a racist or Jim Crow, then stop acting like one,” Democratic state Sen. Nikki Merritt told her white Republican colleagues following the arrest. Former Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams, founder of the voting rights group Fair Fair Action, called the law “Jim Crow in a suit and tie.”

During Reconstruction, racial equality was written into the US Constitution for the first time. It was nothing less than a “second founding,” Columbia University historian Eric Foner wrote in his 2019 book of the same name. Trailblazing Black lawmakers like Turner were elected, and the party that was aligned with Black voting rights made inroads in a region dominated for a century by the party of white supremacy. Multiracial government became a fact of life where white minority rule had been the norm.

The overthrow of Reconstruction was a stark reminder of the fragility of progress on voting rights. The second Reconstruction that began in the 1960s was marked by long, slow advancement that culminated in 2020, when Black voters turned out in record numbers to elect the state’s first Black and Jewish US senators. “After I finished crying, I was just so elated, that Georgia stands alone in the South,” said State Rep. Al Williams, who marched from Selma to Montgomery with John Lewis and was arrested 17 times during the civil rights movement. “A Jewish guy and a Black Baptist preacher—who would have ever thought it?”

But the vicious white backlash that has followed those victories—an attempt to overturn the election, an insurrection at the US Capitol, a record number of bills to restrict voting rights—has all the makings of a concerted attempt to end the second Reconstruction.

The means have changed and grown less violent, but the basic idea is the same: to couch voting restrictions in race-blind language to disenfranchise new voters and communities of color. Once again, the party of white grievance is rewriting the rules of American democracy to protect conservative white political power from the rising influence of new demographic groups. “Nobody’s putting in a literacy test, nobody’s putting in a poll tax,” says Yale historian David Blight. “But there are all kinds of ways for how to just restrict voting this time. Rather than utter disfranchisement, they are obviously going for: Knock off 5 percent of the Black vote, and you can once again win Georgia.”

Rep. Park Cannon is arrested in the Georgia Capitol after knocking on Gov. Brian Kemp’s office door while Kemp signed a sweeping voting law.

Alyssa Pointer/Atlanta Journal-Constitution/AP

In August 1890, ex-Confederate leaders in Mississippi convened to draft a new state constitution that would disenfranchise Black voters once and for all. “Let us tell the truth if it bursts the bottom of the Universe,” said Mississippi Supreme Court Justice Solomon S. Calhoon. “We came here to exclude the Negro. Nothing short of this will answer.”

Reconstruction had brought even bigger changes to Mississippi than to Georgia because Mississippi had a Black majority. More than 225 Black officeholders were elected, including two US senators, a congressman, speaker of the house, lieutenant governor, secretary of state, and superintendent of education. It was the very success of Reconstruction that made white Mississippians so determined to overthrow it.

In 1875, ex-Confederates had retaken the state following the Georgia model: White Democrats formed paramilitary groups and attacked Republican meetings, threatened economic reprisals against Black farmers, and stuffed ballot boxes.

“If a colored man said he was going to register, they advised him not to,” said Aurelius Parker, a member of the legislature. “If he was still determined in his statement that he was going to register, they would tell him that if he did register, he could not vote.” Those who ignored such threats were told, “You had better spend Monday digging a grave for yourself if you intend to vote, for you will not be allowed to live.”

White Democrats weren’t always proud of the methods they used to keep Black people from the polls. “It is no secret that there has not been a fair count in Mississippi since 1875, that we have been preserving the ascendancy of the white people by revolutionary methods,” Judge J.B. Chrisman said during an unusually candid speech at the state constitutional convention in 1890. “In other words, we have been stuffing ballot boxes, committing perjury, and here and there in the state carrying the elections by fraud and violence…No man can be in favor of perpetuating the election methods which have prevailed in Mississippi since 1875 who is not a moral idiot.”

They soon shifted tactics to achieve the same goal. The Reconstruction laws were technically still on the books, and if Republicans, who had taken unified control of the federal government in 1888 for the first time since the Grant administration, passed new legislation to enforce the 15th Amendment, which guaranteed men the right to vote regardless of race, Black people could regain their influence in the state. So Mississippi Democrats attempted something historic, drafting a new state constitution “to effect an electorate under which there could be white supremacy through honest elections,” wrote J.S. McNeily of the Vicksburg Herald.

The constitutional convention established a dizzying array of devices to eliminate Black suffrage, including a poll tax and the disqualification of prospective voters who committed minor crimes like “obtaining goods under false pretenses”—offenses for which Black people were disproportionately charged. The centerpiece of the plan was a requirement that any voter “be able to read any section of the Constitution of this State; or he shall be able to understand the same when read to him, or give a reasonable interpretation thereof.” This “understanding clause” gave local white election officials tremendous discretion to turn away Black people, while permitting local whites who might fail such a test to vote regardless.

There are striking similarities between the Mississippi plan of 1890 and the Georgia plan of 2021. The same pattern that existed during Reconstruction—the enfranchisement of Black voters, followed by the manipulation of election laws to throw out Black votes, culminating in laws passed to legally disenfranchise Black voters—is repeating itself today.

Trump told Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to “find 11,780 votes” to nullify Joe Biden’s victory, and Trump’s lawyer Rudy Giuliani asked the state legislature to appoint its own presidential electors to overturn the will of the voters. When these efforts failed, Georgia Republicans rushed to change their voting laws to make it much easier for Republican candidates to find those votes in future elections—replacing extralegal attempts to rig the election with ostensibly legal ones.

The proponents of these laws have defended them in eerily similar ways. White Mississippians of the 1890s claimed there was nothing racist about their new constitution because it was intended “to correct the evil, not of Negro suffrage per se, but of ignorant and debased suffrage,” said Mississippi Democratic Sen. James Z. George. The “understanding clause” was “an enlargement of the right to vote and not a restriction upon it,” George argued, since it did not disenfranchise voters if they could sufficiently interpret the Constitution—a loophole that, in practice, existed for white people, not Black people.

Similarly, in 2021, Kemp said “there is nothing Jim Crow” about the Georgia law and argued that it “expands access to the ballot box,” pointing to a provision that requires more days of weekend voting. That won’t affect large counties in the Atlanta area that already offered multiple days of weekend voting but will create more voting opportunities for rural counties that lean Republican. Nor did Kemp mention the 16 different provisions that make it harder to vote and that target metro Atlanta counties with large Black populations.

And both plans had built-in backstops in case they didn’t succeed in manipulating the electorate. In post-Reconstruction Mississippi, the lieutenant governor and secretary of state would appoint all the local election officials, who could ensure the results favored white Democrats. This consolidation of election authority was replicated by Democrats across the South. In Maryland, South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana, the governor appointed the county commissioners who selected the election judges. In Alabama and Arkansas, election officials were chosen by a state board led by the governor; in Virginia and North Carolina, the legislature appointed them.

This year, after Raffensperger rebuffed Trump’s demand to overturn the election, the Georgia legislature stripped the secretary of state of his chairmanship and voting rights on the state election board; and lawmakers instead gave the legislature the power to appoint a majority of board members. The board, in turn, has the authority to take over up to four county election boards it deems underperforming. And since November, at least nine GOP-controlled counties have dissolved their bipartisan election boards to create all-Republican panels. Combined with a provision allowing right-wing groups to mount an unlimited number of challenges to voter eligibility, these changes will make it easier for Republicans to contest close elections and possibly overturn the results.

Above: People wait to register to vote in Macon, Georgia, in 1962. Below: Voters in Cobb County, Georgia, wait in line for up to three hours during the 2018 midterms.

United States Information Agency/Getty; Jessica McGowan/Getty

Then, as now, Congress had the power to stop the disenfranchisement of Black voters.

One month before the Mississippi convention of 1890, the House of Representatives passed a bill sponsored by Massachusetts Rep. Henry Cabot Lodge empowering federal supervisors to oversee registration, voting, and ballot counting in the South, and giving federal judges the power to invalidate fraudulent election results. “The Government which made the Black man a citizen of the United States is bound to protect him in his rights as a citizen of the United States, and it is a cowardly Government if it does not do it!” Lodge said.

Senate Republicans also greeted the Mississippi convention with outrage, vowing to approve the Lodge bill when they returned to the chamber that fall. But Democrats staged a dramatic filibuster—the first of many Southern-led filibusters to kill civil rights legislation—giving exhaustive speeches and using a variety of endless procedural delays to derail the bill. Sen. George of Mississippi alone gave three marathon speeches in opposition. “It will never come to pass in Mississippi, in Florida, in South Carolina, or any other State in the South, in any State in the American Union, that the neck of the white race shall be under the foot of the Negro,” he vowed.

With the support of a group of Western Republicans from sparsely populated mining states who feared the expansion of suffrage to Chinese immigrants, Senate Democrats mounted a sneak attack on January 5, 1891. Democrats were quietly told to hastily assemble in the chamber. Democrat Isham G. Harris of Tennessee controlled the gavel while Vice President Levi Morton, a Republican who usually presided over the business of the Senate, was taking a leisurely lunch. As Republicans angrily protested, the assembled senators voted 34 to 29 to scrap the Lodge bill.

Today, the parties have flipped, but the situation is similar. Aided by national dark money groups like Heritage Action for America, Republican-controlled states are rushing to pass new voting restrictions while Democrats in Congress are pushing two sweeping bills to protect voting rights and stop many of these efforts. Once again, these bills are likely to be blocked by a Senate filibuster. Republicans have denounced one of the bills, HR 1, in the same apocalyptic terms that Democrats once used to criticize the Lodge bill. Ted Cruz of Texas called it “the single most dangerous piece of legislation before Congress.”

The failure of the Lodge bill is a stark reminder of the costs of inaction, both for democracy and for the party that supports Black voting rights. Following its defeat, Democrats suppressed the Black vote so efficiently that they gained unified control of the federal government in 1893 for the first time since before the Civil War. They promptly repealed the laws that had been used to enforce Reconstruction and protect Black suffrage.

“Let every trace of the reconstruction measures be wiped from the statute books; let the States of this great Union understand that the elections are in their own hands,” House Democrats wrote in an 1893 report. “Responding to a universal sentiment throughout the country for greater purity in elections many of our States have enacted laws to protect the voter and to purify the ballot.” A similar phrase—“preserve the purity of the ballot box”—was inserted by Texas Republicans in a sweeping anti-voting bill this year and stricken only after Democrats pointed out that it dated back to Jim Crow. (The final version of the Texas bill, which would have curtailed voting methods disproportionately used by Black and Brown voters and made it easier to overturn election results, was blocked in the state House after Democrats staged a dramatic walkout before a midnight deadline, denying Republicans the necessary quorum to pass it.)

Following the adoption of the Mississippi plan and failure of the Lodge bill, by 1907 every Southern state had changed its constitution to disenfranchise Black voters, through poll taxes, literacy tests, property requirements, and complex registration and residency laws. The number of Black registered voters in Mississippi fell from 130,483 in 1876 to 1,264 by 1900; in Louisiana from roughly 130,000 in 1896 to 1,342 in 1904; in Alabama’s Black Belt counties from 79,311 in 1900 to 1,081 in 1901.

By the early 1900s, only 7 percent of Black residents were registered to vote in seven Southern states, according to data compiled by the historian Morgan Kousser, and Black turnout fell from 61 percent of the voting-age population in 1880 to just 2 percent in 1912.

“The failure of the Lodge bill was taken by the white South as a go-ahead,” says Foner. “‘The Republican Party has given up, and therefore we can go forward.’”

Once voting rights are taken away, the history of Reconstruction shows how difficult it is to get them back. If Congress fails to act, don’t expect the courts to step in.

In 1898, the US Supreme Court upheld the Mississippi plan, despite clear evidence of Black disenfranchisement and the racial motivations behind it. The law’s provisions “do not on their face discriminate between the races, and it has not been shown that their actual administration was evil, only that evil was possible under them,” Justice Joseph McKenna wrote.

Five years later, Jackson Giles, president of the Colored Men’s Suffrage Association of Alabama, challenged Alabama’s literacy test on behalf of 5,000 Black citizens in Montgomery. Giles had voted in Montgomery for 30 years before the new constitution disenfranchised him. Yet the Supreme Court said there was nothing it could do to help him. “Relief from a great political wrong, if done, as alleged, by the people of a state and the state itself, must be given by them or by the legislative and political department of the government of the United States,” wrote Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1903.

The states’ rights jurisprudence of the post-Reconstruction court has been resurrected by today’s court, which under Chief Justice John Roberts has gutted the Voting Rights Act, refused to overturn partisan gerrymandering, and almost completely turned its back on efforts to protect voting rights for communities of color. The 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder—when the court’s conservative majority ruled that states like Georgia and Mississippi, with a history of discrimination, no longer needed to clear their voting changes with the federal government—had an impact similar to Hayes’ decision to withdraw federal troops from the South in 1877. The federal government, it was clear, had abandoned its commitment to enforce the Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution.

“The only thing that protects people’s access to the vote is federal protection, federal intervention,” says Northwestern University historian Kate Masur. “If nothing else, that pattern is clear in US history.”

On March 17, 2021, a week before Georgia passed its voter suppression law, Raphael Warnock gave his maiden speech on the floor of the US Senate. Like Henry McNeal Turner, Warnock was a preacher before he became a politician, and his election was followed by a horrific act of violence.

“We elected Georgia’s first African American and Jewish senator, and, hours later, the Capitol was assaulted,” Warnock told his colleagues. “We see in just a few precious hours the tension very much alive in the soul of America.”

When he was born in 1969, Warnock said, Georgia still had two arch-segregationist senators, Richard B. Russell and Herman E. Talmadge. After the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, Talmadge predicted that “blood will run in the streets of Atlanta” if schools were desegregated. When Talmadge’s father, Eugene, the state’s longtime segregationist governor, was asked in 1946 how he would keep Blacks away from the polls after the federal courts invalidated the state’s whites-only primary, he picked up a scrap of paper and wrote a single word: “pistols.”

Warnock noted that he now held the Senate seat “where Herman E. Talmadge sat.” That was progress, but the immediate backlash showed just how entrenched the reactionary forces in American politics had become. At the time, 250 bills had been introduced at the state level to restrict voting rights. One month later, when Warnock testified at a Senate hearing on “Jim Crow 2021,” the number of proposed restrictions had increased by more than 100, and Georgia was at the center of a heated national debate over voter suppression. “I come here today to stress the critical need for the federal government to act urgently to protect the sacred right to vote,” he said.

The last time that happened, when Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, he compared it to the last battle over slavery, to redress not just the country’s original sin, but the failed hope of Reconstruction. The Union victory at Appomattox was “an American victory but also a Negro victory,” Johnson said. “Yet for almost a century, the promise of that day was not fulfilled.”

Warnock said he thought often about what would have happened if the Voting Rights Act had not passed in 1965, if the country had not intervened to enforce the 15th Amendment after it had been ignored for so many years. “If we had not acted in 1965, what would our country look like?” he asked his fellow senators. “Surely, I would not be sitting here. Only the 11th Black senator in the history of our country. And the first Black senator in Georgia. And maybe that’s the point.”