Gozargah school in Kabul in 2008. Courtesy of Adriana Carranca

In the days before the Taliban seized control of Kabul and President Ashraf Ghani left Afghanistan, veteran Brazilian journalist and writer Adriana Carranca received a message from an 18-year-old Afghan girl.

Carranca, the author of several books including Afghanistan After the Taliban (2011) and Malala, the Girl Who Wanted to go to School (2015), had met Laila (a pseudonym to protect her identity) during her second trip to the country in 2011. At the time, Laila was eight years old. She was a promising cellist who attended the Afghanistan National Institute of Music—an academy founded in 2010 by Dr. Ahmad Sarmast, an Afghan who had returned to the country after seeking refuge in Australia during the years of Soviet occupation—and participated in the nation’s first all-female orchestra.

Laila’s message to Carranca was cheerful. The young musician had received a scholarship to study classical performance at a prestigious arts institution in Michigan and had started a fundraising campaign to cover expenses for the trip. But the next time they spoke, on August 16, she told Carranca that she hasn’t been able to leave Afghanistan and is terrified of stepping outside the house. The music school, which had shut down because of the coronavirus pandemic, is likely not resuming activities, since during the first period of Taliban ruling music was outlawed, as was women’s education. Her dream has been cut short by the Taliban takeover that ensued the US withdrawal from the country 20 years after 9/11.

“I cried while talking to her,” Carranca says. “What will happen to these girls?”

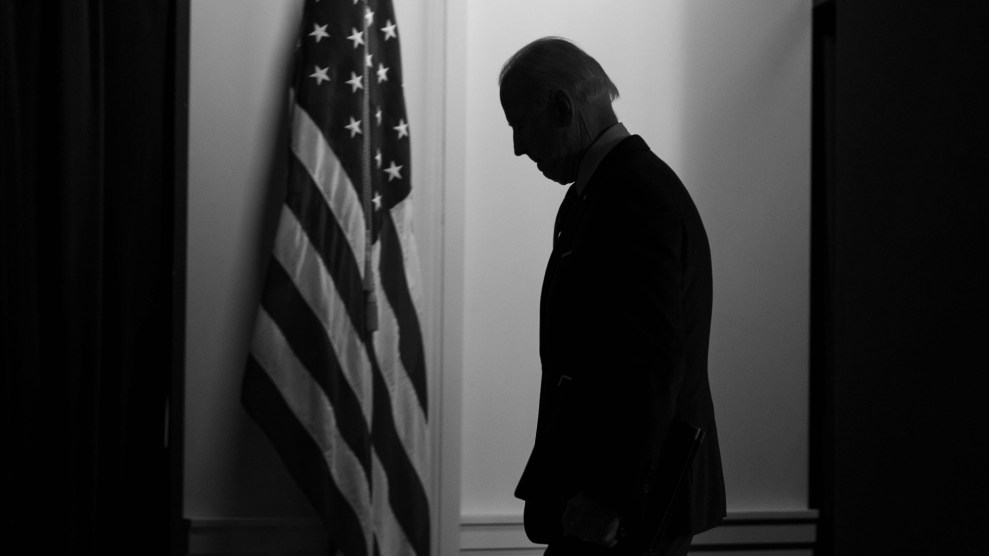

Between 2008 and 2012, Carranca traveled to Afghanistan four times and made several more trips to the border with Pakistan. This past week, as the world watched a monumental humanitarian crisis unfold, Carranca has been using her social media channels and giving interviews to Brazilian outlets highlighting stories of Afghan people whose lives have been upended by decades of war and foreign invasion.

She described a 36-year-old illiterate woman who lost both of her arms in a car bomb attack. She has posted about an Italian-born physiotherapist with the Red Cross who has lived in Kabul for three decades and has become known as the “Afghan angel” for his work rehabilitating victims of land mines and armed conflict.

Carranca and I both attended Columbia Journalism School in 2017 and 2018 and were fellows at the Global Migration Project. I called her at her home in Brazil and we spoke about her experiences reporting from Afghanistan, how Afghans’ sentiment about the US presence changed over time—from hope to resentment and desolation and now despair—and what the future holds for those who stand to lose the most—the young and the women.

When did you begin reporting in Afghanistan?

I first went to Afghanistan as a reporter in 2008 right after the election of Barack Obama. At the time, we thought that would be Obama’s big war since military actions in Iraq were in decline. We also knew that the Taliban wouldn’t hand Afghanistan over to the Americans so easily. If you look at the history of the Pasthun people, the Taliban’s ethnic group, their strategy has always been to retreat and then when least expected they descend from the mountains and take it all over again. Because Osama Bin Laden still hadn’t been found, Obama needed to give 9/11 a closure or the war would never end. It was already the longest American war. The war in Afghanistan was an attempt to respond to the pain and drama of the attacks, even though none of the terrorists were Afghans.

But the reason for the war goes way back. After the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the United States started funding, arming, and training Afghan militias to fight communism. These militias recruited children among families who had sought refuge in Pakistan during the Soviet regime. Ten years later when the Soviet occupation ended, the United States left Afghanistan in the hands of these militias and the country fell into a civil war. That’s how the Taliban was created.

Do you think it’s a surprise, then, that the Taliban has retaken the country?

People have been talking about a comeback of the Taliban, but the reality is they never went anywhere. They strategically retreated from the government but as soon as the United States entered the country in 2001, they started mounting the insurgency and gaining territory in 2003 when the United States turned to Iraq. In 2008, a large part of the country, mainly the rural provinces with less presence of the US military, were already controlled by the Taliban. They had offices in Pakistan and the international community knew about it. They have always been there. I don’t understand what the surprise is. What’s surprising is the fact that the international community abandoned and lost interest in Afghanistan and suddenly are finding out that the insurgence was alive.

Was there ever hope that you saw?

Back in 2008, it was very clear that there was still hope, mainly among the young people in urban areas. You had this generation that was born and raised with the internet, access to information, and foreign presence. That didn’t happen before with the Taliban or the Soviets. It’s a generation that wanted more from the world and they benefited a lot from US occupation. Many youth moved to Kabul because the whole world disembarked there and that’s where the jobs were. People needed drivers, translators, local reporters. I met a girls boxing team who, as a form of resistance, practiced in a stadium where the Taliban used to stone women and Kabul’s first female graffiti artist who covered the walls destroyed by the war with art.

But elsewhere, little changed. When I visited for the first time, 80 percent of the country didn’t have electricity. I interviewed a 36-year-old woman who lived outside of Kabul and she had never seen a fridge. The milk in the morning came from a girl with a goat and there was no water to shower at home so women went to bath houses. That was the real Afghanistan.

Did anything change after the United States killed Osama Bin Laden?

After 2011 and the death of Bin Laden, Obama announced a gradual withdrawal plan from Afghanistan. The Arab Spring also happened around that time and humanitarian aid started going towards Egypt and Syria. Once the United States and other countries leave, so does the money. I heard about several schools and projects that closed. In Kabul, where foreigners were circulating in armored cars, there were miserable camps for the internally displaced. People froze to death in the winter. They grabbed my arm asking for a visa to leave the country. Afghanistan was essentially abandoned. From then on, they became the second largest group of refugees. I met a young man who tried to cross into Turkey with his family and lost almost all of his relatives, including his five-month pregnant wife. He looked for her for a year but her body was never found. He couldn’t get asylum anywhere so he returned to Afghanistan. He recently contacted me to say he and his mother are desperate.

The United States could have left Afghanistan in the hands’ of a new generation, not the Taliban. But they didn’t invest enough in strengthening institutions and empowering new generations in urban areas who really wanted to rebuild the country and take over the reins. In 20 years, you could have transformed Afghanistan and that generation.

How has the Taliban itself changed over the last 20 years?

The Taliban, which means “student,” never had international aspirations like ISIS. They were trying to implement a government in accordance with their millenary, tribal traditions. Their agenda was domestic. But during the occupation, they became international. Now they have Twitter, Facebook, a digital magazine, a spokesperson. I was a little hopeful that by going global they would realize the benefits they could have by being more moderate, but now China and Russia have already declared support for the Taliban. If money comes in from these countries, they won’t need the Western democracies and we know that China and Russia aren’t exactly human rights defenders.

The new leadership has also talked about moderation and preserving women’s rights, but it’s almost impossible to believe it. The new commander is a religious leader from the old guard and the vices are one of the founders of the Taliban and a leader of the Haqqani network, one of the most radical and violent terrorist groups. Change will depend on how much the “new old” Taliban wants to have relationships with the world.

What do you think happens next?

Most Afghans are just trying to get out. I was inundated with messages from Kabul. People asking for help to leave, asking about visas. They are desperate to cross the border and then think about what to do next. The Taliban regime was bad for everyone. But the generation that managed to go to school and grew up in contact with the Americans will now be the ones most harmed by the return of the Taliban. There’s a lot of fear and the sentiment among this youth is that of the end of a dream. It’s a feeling of not knowing if they’ll ever pick up a book again or if, as a women, they’ll be able to leave the house.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.