butenkow/iStock/Getty Images Plus

To fill the post of chief agricultural negotiator at the United States Trade Representative’s office, the Biden administration dipped into California’s hot, dusty, drought-plagued San Joaquin Valley and plucked out an almond-industry lobbyist. According to the job’s official description, the negotiator’s main function is to “conduct trade negotiations and enforce trade agreements relating to United States agricultural interests and products.”

Tapping Elaine Trevino, president of the Almond Alliance of California, doesn’t mark a break from past administrations in terms of placing this particular post in the hands of a powerful, export-dependent agriculture sector. President George W. Bush gave the job first to an Iowa soybean flack, then to a GMO seed exec. President Barack Obama turned to a lobbyist for the seed/pesticide industry; while President Donald Trump bestowed the position to a guy who had served as chief economist for the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association.

But Biden is favoring the $6 billion almond industry at a particularly fraught time in its history. The ever-expanding groves of California’s Central Valley churn out nearly 80 percent of the globe’s almonds. The industry’s dramatic expansion over the past 30 years means that to stay profitable, almond farmers and processors require a fast-growing market for the delicious nut.

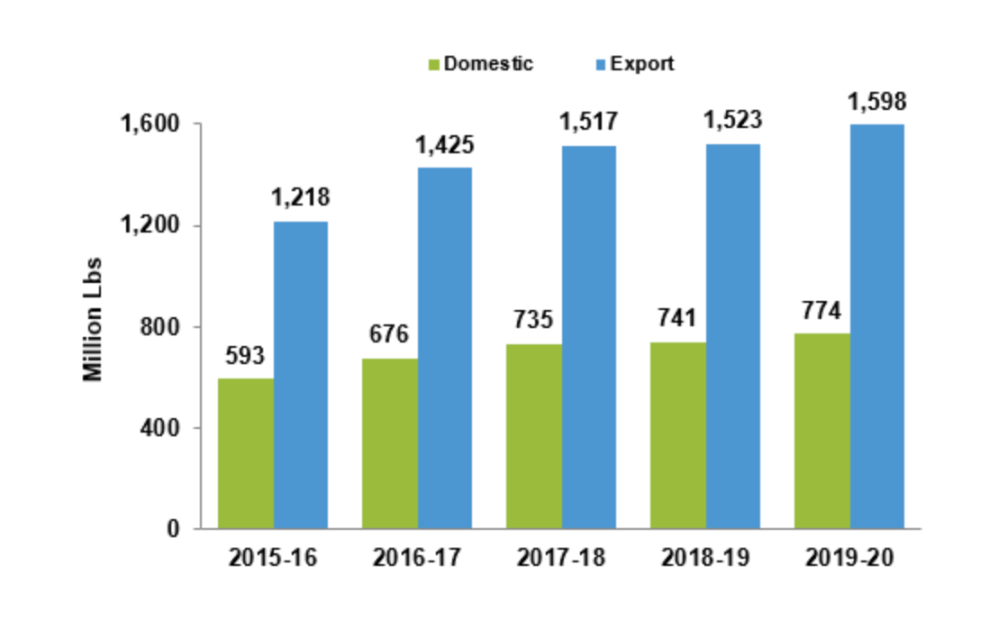

That’s where foreign markets come in. “As California almond growers consistently produce yields at record or near-record levels year after year, it is important that those nuts find a home,” the California Almond Board recently stated. “Increasingly, that means expanding existing export markets and continuing to grow demand in those regions, while always keeping an eye on new opportunities globally.” About two-thirds of US-grown almonds flow out of the country, and if that trend slows down, the industry will face a glut, which would bring prices down and wipe out profitability.

This chart, tracing annual US almond output moving to domestic and export markets, tells the story of an industry heavily reliant on exactly what Trevino is tasked with doing in her new job: finding a foreign home for lots and lots of almonds.

For decades, the situation has worked out splendidly. People in Europe and Asia happily buy up US almonds, keeping their price up; and farmers keep taking advantage of the rising demand by planting more almond groves. Similar dynamics hold for pistachios and walnuts, and those nut crops have taken over the valley, pushing pretty much everything else to the margins, as this chart by UC Davis researchers shows. Note how the expansion continued during “dry or critically dry” years, i.e., droughts.

The problem, as I showed in this 2015 feature article and in my 2020 book Perilous Bounty, is that the industry has expanded beyond the limits of the region’s climate-change-haunted water resources. The current drought, the second historically severe one to grip the region in the past decade alone, is yet again exposing the folly of devoting so much land to such water-sucking crops in what is essentially a desert. The San Joaquin Valley’s 4 million residents are already seeing wells go dry as nut farmers dig ever deeper wells to capture water from ever-sinking aquifers.

Rather than empowering an almond flack to peddle more product overseas under the seal of the US government, the Biden administration should be helping California figure out how to rein the industry in—before all the water’s gone.