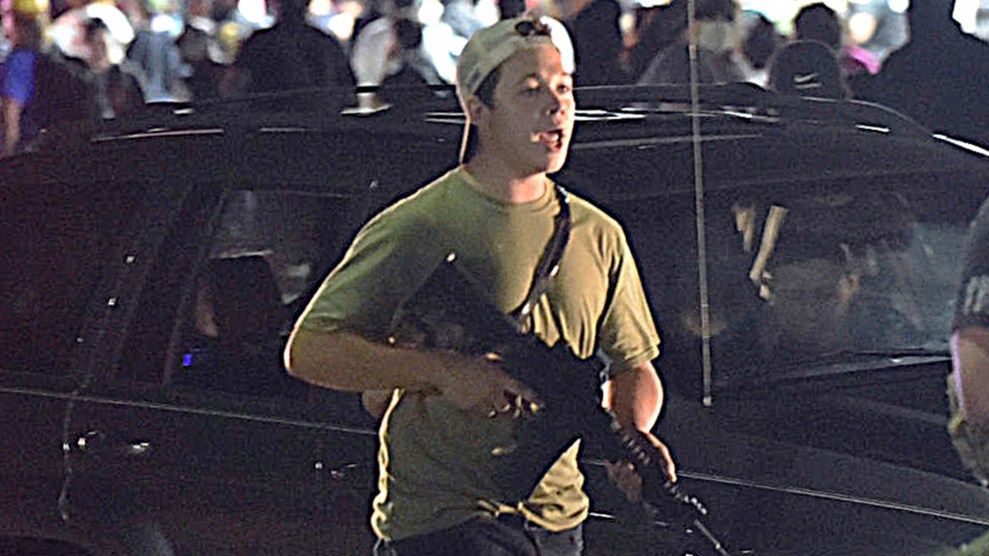

Kyle Rittenhouse speaks with his attorneys.Sean Krajacic/Pool/Getty

Two days before a nearly all-white jury bought Kyle Rittenhouse’s claim he was acting in self-defense when he shot three men, killing two, at a Black Lives Matter protest, Maddesyn George, a 27-year-old Native mother, was sitting in a courtroom in Eastern Washington, waiting to learn how many years she would have to spend in federal prison for a shooting a white man she said had raped her.

George, a member of the Colville Confederated Tribes, admits she killed Kristopher Graber in July 2020. The two had been friends; in a police interview, she said was at Graber’s house doing scratch-off tickets when he got on top of her and raped her with a vibrator. When she protested, he pulled out a gun, George told the tribal detective. Graber eventually fell asleep, and George took the gun from him, along with cash and drugs, according to prosecutors. Then she left. The next day, Graber went out looking for her, found her sitting in a locked car, and confronted her. In the altercation, she shot him once through the window, killing him.

“I was like panicking cause I was like, ‘Oh, fuck, the window’s open this much, like he’s going to fucking, he is going to get me,” George told the tribal detective shortly after the shooting. “So then I got the gun off the floor.”

Yet unlike Rittenhouse, George never got a chance to argue that the shooting was done in self-defense. Last summer, federal prosecutors filed a motion trying to block her from making that argument at trial, arguing that she was the “initial aggressor” in the shooting, and arguing the “purported assault” wouldn’t be enough to justify a self-defense claim.

A couple weeks later, staring down the possibility of a 35-year sentence, George decided to take a plea deal for voluntary manslaughter and drug possession, according to Steve Graham, her lawyer. On Wednesday, US District Judge Rosanna Malouf Peterson sentenced George to six and a half years in federal prison, lower than the expected range, and far less than the 17 years prosecutors had asked for. “Everybody outside the courthouse was just delighted,” Graham says. “Because the sentence was a third of what the prosecutors asked for, and then also because the judge said she believed Maddesyn. And she articulated that she fully understood.”

Yet George’s sentence is a stark contrast to Rittenhouse’s not guilty verdict, delivered by a jury on Friday. “Here we have Rittenhouse gas up his car, cross state lines, claiming to defend himself, when Maddesyn George was in her own reservation, hiding out from this white man who crossed reservation lines to try to come after her,” Graham says. The two cases played out in separate jurisdictions, with very different sets of facts. But their outcomes—Rittenhouse goes free, while George is going to prison—illustrate larger disparities in whose claim to self-defense is seen as legitimate, according to Caroline Light, director of undergraduate studies in the Program in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Harvard University. An Urban Institute study, for instance, found that homicides with a white perpetrator and a Black victim are 281 percent more likely to be ruled justified than cases with a white perpetrator and white victim. Meanwhile, according to a survey of 608 women imprisoned for murder or manslaughter convictions, 30 percent said they were convicted after trying to protect themselves or loved ones from physical or sexual violence.

After the Rittenhouse verdict came down, I called up Light, the author of Stand Your Ground: A History of America’s Love Affair with Lethal Self-Defense, to talk about the connections between his case and George’s, and these larger trends.

We just got news that Kyle Rittenhouse’s self-defense claim was successful, and the jury acquitted him of all charges. What do you make of the verdict?

It’s devastating. What happens in these courtrooms affects our lives and our culture and our behaviors. It sends a message to certain people that if they want to take a deadly weapon into spaces where it could get volatile, and then claim—after they kill people—to have been in fear for their life, a court is likely to exonerate them. When we see demonstrations against anti-Black violence, against hate crimes, against police violence, does this decision then license people who feel like those demonstrations themselves are an act of aggression, to go in with their firearms and start shooting? That, to me, is the torturous logic at the heart of this decision.

In a way, this expands the idea of self-defense, right? If Kyle Rittenhouse put himself in this situation, and yet he could successfully claim self-defense, that’s sort of expanding the notion of what qualifies. Might that be good for other people whose self-defense claims typically aren’t believed—like women who kill abusive partners in self-defense?

It might affect, say, a white woman who wants to take a firearm into a Black Lives Matter protests and threaten demonstrators. But it will not expand the terrain of self-defensive capacity for a woman who uses a firearm to defend herself from an angry or violent boyfriend.

Why not?

For women, for sexual minorities, gender minorities, and people of color, and low income people and people with drug addiction, and houseless people—the various, layered social vulnerabilities that put people in a position where they may need to use lethal self defense—those are the very people who are not going to be able to claim the same kinds of immunities as someone like Kyle Rittenhouse or George Zimmerman.

The law is written to appear neutral. It doesn’t have any reference to different races, or different genders, or class, or anything like that. But the way it plays out in the courtroom is always already stacked against people who are occupying different social vulnerabilities, especially multiple social vulnerabilities. So someone like Maddesyn George is not going to benefit from the self-defense expansion that we will see in the wake of Kyle Rittenhouse’s trial.

Because she’s not a white man.

It’s about both actors. Part of what happens in the courtroom, with a Kyle Rittenhouse or George Zimmerman, is that they succeed in magically reversing the roles of victim and perpetrator. [Rittenhouse’s] defense was successfully able to position him as a victim of violence rather than a perpetrator of violence. Framing it as, “he had no choice, and had to defend himself”—a rational response to a reasonable threat.

During slavery, and at the very beginning of the settler colonial state, there were people who justified colonial violence based on a need to protect themselves from “dangerous savages” or other offensive terminologies for Indigenous people. And so armed white masculine violence could easily be justified as protective and as virtuous violence rather than aggressive and hostile.

If we look at someone like Kyle Rittenhouse, he looks very much like the average mass shooter. What we had were people trying to disarm a potential threat. It turned out, he was indeed a real threat. And yet, the court exonerates him—and treats the people who tried to disarm him as the perpetrators. That, to me, is devastating.

You’ve spoken before about how important it is which events get included of the chronology of a self-defense case—which events the jury looks at when they’re deciding whether it’s provocation, self-defense, or something else. Because Maddesyn George took a plea deal, her attorney Steve Graham never got a chance to make this argument at trial, but I asked him where he would start the clock if he were presenting this case to a jury. I’d love to read you his response. He said:

During colonialism. That’s when we would talk about the clock starting. And the fact that she was on her lands. That she was here first, her ancestors were here first. She hid out there. We would start with the fact that she was sexually harassed by a white cop—and we documented that, and the judge believed her about that. It would start with the fact that not much was really done when she was a victim of prior crimes. It would start with Mr. Graber, essentially being allowed to run amok up there, and sell drugs, and hurt women with impunity. And then it would kind of come around to the culmination of the real unspeakable indignity that she suffered at his hands.

That’s fantastic. However, the prevailing legal system doesn’t do it that way. We tend to interpret especially female perpetrators of violence through a very particularly curated chronological lens. Are you familiar with the case of Brittany Smith? This was a woman who killed the perpetrator in her own home, and she was defending her brother. In the trial, they were throwing out the evidence—horrible evidence of physical violence, all kinds of evidence that this man had brutalized her—and they spliced it out. It was like they did this curation of chronology that completely excluded all the evidence of sexual violence and harm that had preceded the deadly encounter.

Is that because she didn’t shoot him right in the middle of him raping her? Like, what does it take?

That’s the issue.

What happens in the trials around women who use self-defense against partners or acquaintances is what we believe about gender and race and class and drug addiction, these things are stacked against them when they try to claim the status of “victim.” The law is always skeptical of any woman’s claim that she was sexually assaulted. And the law, and our dominant culture, is always skeptical of a person of color who takes the life of a white person. There’s just so many preconceptions and biases baked into our culture that were stacked against Ms. George from the get-go.

There really are very few cases you can point to where a woman who kills or maims the man who sexually assaults her, is exonerated. She’s probably going to go to prison. And if she doesn’t go to prison, she’s going to plea to something so that she can avoid prison time. But she will be criminalized for taking that life.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

This article has been updated and corrected. A previous version of this article misstated how people are taught to respond to active shooter situations. In fact, the FBI instructs people to first run from an attacker, to hide if fleeing is impossible, and to fight back as a last resort.