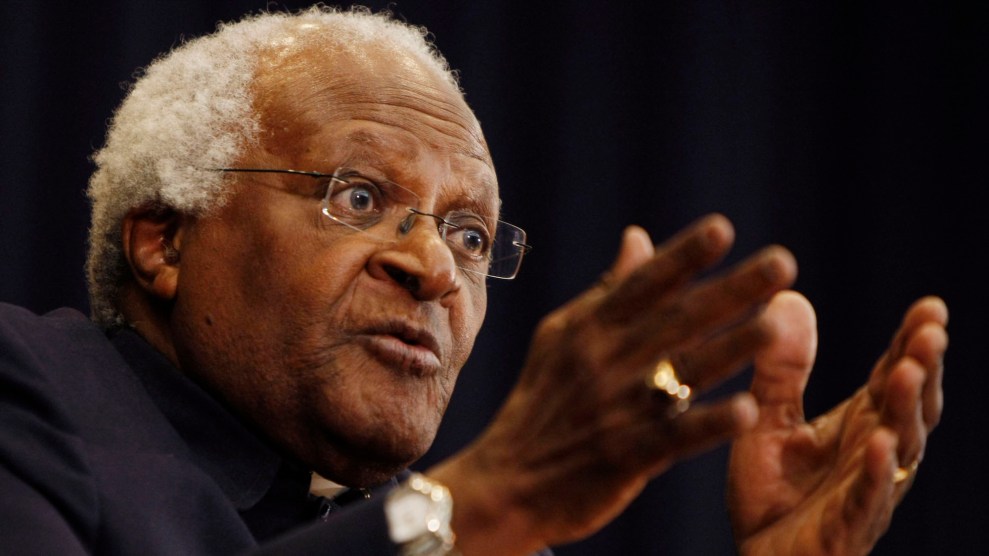

Desmond Tutu in Washington, 2008. Gerald Herbert/AP Photo

Nearly a half-century ago, when apartheid, a racial caste system rooted in colonialism, ruled South Africa, a middle-aged cleric became the first Black dean of Johannesburg, which is an important position in the Anglican church. He could have wrangled a special permit to live in the city’s prosperous white quarter where the church was located, and emerged as a de facto token of phony progress for the racist regime.

Instead, he chose to live in the township of Soweto, home of the impoverished Black working class that made the South African economy hum. Rather than serve as window dressing for the white elite, Desmond Tutu—who died at 90 on Sunday after a 24-year bout with cancer—became its worst nightmare, challenging the system and ultimately helping hasten its demise.

“At a time when the African National Congress’s leadership was either in jail or in exile, there was Tutu—cassock flowing, crucifix swaying front and side, as he strode through the brutality of the townships and the mendacity of apartheid,” the UK journalist Gary Younge wrote in an excellent 2008 profile in the Guardian well worth reading today.

Unsparing in his critiques of the regime, Tutu also preached non-violence and unity among its victims as they sought to overthrow the tyrants. In those years, his routine involved “delivering blistering attacks on the regime one minute,” Younge wrote, and “diving into a crowd to save a suspected ‘informer’ from being necklaced [by anti-Apartheid activist] the next.” He was jailed at least once for his activism; but only for a few hours, possibly because the apartheid regime was wary of turning another political prisoner into a global cause celebre, as it has done with Nelson Mandela.

Even so, using the power of his pulpit and his position on the ground in South Africa’s segregated townships, Tutu emerged as a global celebrity anyway, winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984. When apartheid crumbled a decade later, the clergyman’s agitations for justice—no matter the popularity of the cause—had only just begun.

He chaired South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which took on the monumental task of delivering justice for apartheid’s crimes without tearing up a racially divided society. The strategy was to give the regime’s victims the chance to formally testify and document the wrongs done to them and receive reparations, and allow the perpetrators the opportunity to seek amnesty after admitting their crimes.

Formally concluding in 2001, the TRC left behind a complex legacy. For Black South Africans, the televised hearings provided “an acknowledgment of the daily horrors that they were subject to during apartheid,” Ereshnee Naidu-Silverman, senior director for the Global Transitional Justice Initiative, wrote in a 2019 Washington Post op-ed. “With testimony from 21,000 victims, the 2,000 public hearings and 7,112 amnesty applications made it difficult to cling to denialism because a collective narrative of a racist past began to emerge.”

Yet the TRC’s call for broad-based reparations for Black South Africans ended up being ignored by the government, while few perpetrators admitted to crimes or were punished for them, she writes. Still, the commission remains a model for societies trying to peacefully move beyond systemic wrongs in a just way—imagine if the United States had held public hearings, say, on the horrors of the Iraq War or those of the Jim Crow era.

In the 2000s, Tutu remained an outspoken crusader for justice, repeatedly clashing with the ruling African National Congress, which ruled South Africa after apartheid, over various corruption scandals. Tutu also used his platform to speak out on a range of global affairs, from the Israeli occupation of Palestine to the Iraq War, which he opposed from the start; from toothless international climate policy to homophobia within religious institutions.

When courageous fighters for justice die, mainstream figures seek to sanitise them and strip them of their radicalism.

So let's remember Desmond Tutu as the implacable champion of the oppressed – and the fervent opponent of tyranny – that he actually was.

RIP. pic.twitter.com/iQXdsKoG8Y

— Owen Jones 🌳🌹 (@OwenJones84) December 26, 2021

Younge’s 2008 profile paints him as a playful, introverted man who really just wanted to be loved. “They call him Father, but as he sits at the breakfast table eating Cheerios with fruit and yogurt, giggling as he teases and is in turn teased, Archbishop Desmond Tutu looks more like a mischievous little boy,” Younge wrote. “He has been known to bust out a dance move whether or not there is a dancefloor in sight.”

He remained active well into his 80s. “Ever the rebel, he came out in support of assisted suicide in 2014, stating that life should not be preserved ‘at any cost,'” reports the BBC in its obituary. “In 2017, Tutu sharply criticised Myanmar’s leader and fellow Nobel Peace laureate, Aung San Suu Kyi, saying it was ‘incongruous for a symbol of righteousness’ to lead a country where the Muslim minority was facing ‘ethnic cleansing.'”

Tutu is gone, but his memory—and if we’re lucky, his example—will live on. For him, using his voice to defend marginalized people against oppression was a kind of vocation, a life’s work. And so was maintaining a sense of humor.

President Joe Biden has not yet released a statement, but former President Barack Obama wrote:

Archbishop Desmond Tutu was a mentor, a friend, and a moral compass for me and so many others. A universal spirit, Archbishop Tutu was grounded in the struggle for liberation and justice in his own country, but also concerned with injustice everywhere. pic.twitter.com/qiiwtw8a5B

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) December 26, 2021