When Albert Diaz, then 41, took his seat in the Social Security Administration’s hearing room in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, in October 2011, he had to lower himself onto his left buttock to avoid stabbing pain in his right leg. His dominant arm, the right one, was locked in a brace to keep it from curling in toward his body. He shook uncontrollably, a side effect of an electrical stimulation device implanted in his spinal cord to manage relentless pain. Three years earlier, Diaz had fallen backward three stories down an elevator shaft while working as a maintenance director in a luxury apartment building. Since the accident, his family of nine had relied largely on his wife’s teaching salary. His application for federal disability benefits was denied, and after waiting a year for a hearing, he’d come to appeal that decision before an administrative law judge (ALJ).

During the half-hour hearing, the judge asked him whether he attended church or belonged to any clubs, what TV shows he liked, and if he had any hobbies. They talked about his pain and how his family has to help him bathe, get dressed, and shave. Following his testimony, a vocational expert spent a few minutes testifying about what someone in Diaz’s condition could do for work. The conversation went like this: First, the judge asked the expert to imagine a hypothetical person of Diaz’s age, education, and work experience. Now, she said, imagine that this person can do light work, but the light work is limited. “There would be a bilateral lower extremity push/pull limitation,” she clarified, “occasional climbing, balancing and stooping but never on ladders, never kneeling, crouching or crawling. There would be a bilateral, overhead reach limitation, a need to avoid vibration and hazards.”

The judge then asked the vocational expert whether there were any jobs, anywhere in the economy, suited to such a person. Considering only the factors the judge had described, the expert answered that the person could be a “greeter/host,” and indicated that there were about two or three hundred such jobs in northeastern Pennsylvania. Or maybe a “price marker”—who attaches price labels to merchandise—1,100 to 1,200 jobs.

Two months later, the judge denied the claim, citing her belief that Diaz was able to do things like “perform occasional climbing, balancing, and stooping”—which is to say, she thought he could still work. In the nearly eight years it would take him to successfully appeal that denial, Diaz lost his house.

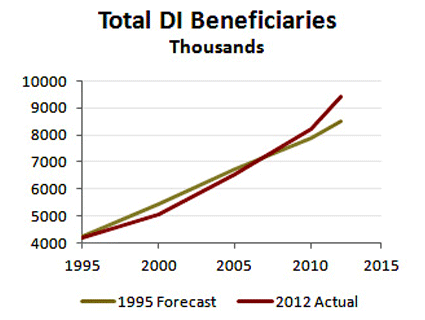

With a bite out of every paycheck, workers pay into the federal system of Social Security Disability Insurance just in case something happens that makes them unemployable. (A parallel program, Supplemental Security Income, or SSI, provides payments to low-income people with disabilities). Of the roughly two million disability claims the SSA receives each year, two-thirds are initially denied. Those who appeal get their claims reconsidered, and if they’re denied again, which most are, they go before an ALJ. It’s the claimant’s best chance for a reversal—last year, slightly more than half of such claims were approved.

A disability appeal hearing can seem surreal to an outsider. Unlike a court proceeding, it involves little storytelling or persuasion. And it’s only glancingly related to a claimant’s experience of impairment. “Disabled is a legal term, not really a medical term,” says Amy Vercillo, a vocational counselor and long-time SSA vocational expert. The government’s definition of a disability requiring compensation is agonizingly specific, focusing on the minutiae of how an impairment changes a person’s capacity to, say, reach forward, bend over, or lift 10 pounds. ALJs are tasked only with determining whether the claimant fits that definition. The objective fairness of the outcome depends entirely on how well the judge, vocational expert, and claimant’s representative—if they have one; it needn’t be a lawyer—can describe the claimant’s disability in bureaucratic doublespeak.

David Chermol, Diaz’s lawyer, introduced me to Diaz because his disability is so obvious, as was the system’s failure in his case. But Chermol says it’s common for the objective reality of a claim to get so chewed up by the hearing process that it becomes unrecognizable. “The only unusual things about Albert’s case are that the injustice was fought and the right thing eventually happened,” he says. “Other than that, absolute bullshit like this is routine.”

It’s not hard to see how the process can go off the rails. ALJs have to absorb hundreds of pages of medical records and testimony per claim, yet the SSA expects them to issue 500 to 700 decisions every year. The vocational experts, most of whom have day jobs in rehabilitation, not statistical analysis, have mere minutes to identify jobs and extrapolate from broad Department of Labor statistics and census data how many positions exist.

In identifying jobs, they must reference the grandiosely named Dictionary of Occupational Titles. First published by the U.S. Department of Labor in 1939 as a tool for job placement during the Great Depression, it describes in detail how nearly 13,000 jobs, from tire mold engraver to coyote hunter, are done. That granularity has made the DOT the central resource for SSA disability adjudication since the program’s inception in the 1950s, but it’s also made the book increasingly difficult to adapt to the changing economy. Most of its job descriptions haven’t been updated since 1977 (and none since 1991). In one entry last updated during the Carter Administration, the book describes an addresser as someone who uses a typewriter to print addresses on envelopes. Ten years ago, the SSA contracted with the Bureau of Labor Statistics to begin the process of replacing the DOT with a database that can be kept up to date, but it’s still not operational.

A competent vocational expert can make up for the DOT’s limitations using other data and their own experience to bridge the gaps between the book and reality (addressers now check rejected labels on Amazon packages). But Vercillo told me many are not trained for that. “You have to speak the language and address the issue of how disability is defined within that system,” she says. But at the paltry SSA pay rate of $107 per hearing, it’s hard to find competent experts willing to put in the time.

As a result, vocational expert testimony can be wildly inconsistent from case to case. In one hearing that was challenged in the Federal 9th Circuit in 2017, a vocational expert testified that there were 5,000 jobs tying tobacco leaves in California, a state not known for its tobacco farms.

“I don’t think it’s fair for a system to have one vocational expert telling me that there are 2,000 surveillance systems monitor jobs in the national economy and the next vocational expert in another hearing telling me, well, there really aren’t any surveillance system monitors, or there are 50,000,” says Judge David Hatfield, who has held several positions in the SSA adjudication system, including as chief administrative law judge. He now consults for Chermol’s firm writing briefs and helping with federal appeals.

Some federal circuit court judges have attempted to impose a rule that would nullify vocational experts’ testimony unless they show their work, but in the 2019 case Biestek vs. Berryhill, the U.S. Supreme Court effectively ruled that the expertise of vocational experts can be taken as a given, even if they don’t.

Compounding the problem, few claimant representatives know how to properly challenge expert testimony or the judge’s interpretation of it. (During Diaz’s 2011 hearing, his previous lawyer got confused by the judge’s hypothetical, mumbled an apology, and then asked the judge for help submitting his travel voucher.)

It’s difficult to say how often all of this results in a fair decision. An internal SSA review performed in 2015 found that ALJs correctly denied claims 98% of the time, but that was a “paper audit” that only took into account the information gathered by the ALJs, not whether they gathered all the information available.

“In particular for denied applicants, the determination process is really a disservice,” says Jack Smalligan, a senior policy fellow at the Urban Institute and former deputy associate director at the Office of Management and Budget, where he oversaw the SSA’s programs through four administrations. Smalligan cites evidence that claimants who spend years appealing have trouble reentering the workforce if they are ultimately denied. He thinks the SSA should shorten the wait by beefing up its pre-hearing reconsideration of claims—spending more time assessing applicants’ conditions and making the process more consistent across the country. “I would just as soon have as few people go before an ALJ as possible.”

By 2014 the financial strain had become too much for Diaz’s family, and he and his wife filed for bankruptcy. It’s not an uncommon outcome—from 2014 to 2019, 48,000 applicants waiting for an appeal decision had to do the same. The bank foreclosed on the Diazs’ home and they moved into an apartment with their three youngest children. “I had no choice,” he told me.

In the meantime, he appealed his disability denial in federal court, where a judge remanded his case to the same ALJ who’d rejected him three years earlier. Diaz’s new hearing took place one year later. The judge described her hypothetical person and asked for jobs. The vocational expert suggested information clerk, credit authorizer/checker, or surveillance video monitor. The hearing lasted exactly half an hour. And the result, which came nearly six months later, was no different. The judge denied him again.

Again Diaz appealed, waiting two years more while the system churned through its backlog. (A recent GAO report found that the appeals process can take dangerously long for the most vulnerable applicants—from 2008 to 2019, over 100,000 people died waiting for a decision). This time, a different federal judge remanded his case to a different ALJ, who questioned the same vocational expert more carefully this time. Chermol’s co-counselor Ashish Agrawal sussed out the hypothetical a bit more, clarifying that reaching, especially with the dominant arm, would be a problem. The vocational expert concluded that the jobs she’d listed in the previous hearing—including the video monitor job, which hasn’t been updated in the DOT since 1986 and these days requires keyboarding—might be hard for the hypothetical claimant to do.

The new ALJ approved him for benefits but misread his medical records as showing that his condition had improved, so the back pay he received only covered some of the time since his accident. He appealed yet again. A third federal judge, clearly frustrated with the handling of the claim, ordered the SSA to approve it in full one year later.

Chermol’s clients, who he says include workers like Diaz, a 9/11 firefighter, and a veteran whose disability led to homelessness—represent a tiny fraction of the tens of thousands of Americans who are denied disability benefits at the hearing level each year. (There were more than 125,000 in 2021.) Chermol is a former SSA insider—he spent 12 years defending the agency against challenges like Diaz’s. He believes in the SSA and that by and large its people are devoted to helping those who need it most. But he saw a lot of genuinely disabled people with either no or bad representation losing out on benefits, and eventually got “grossed out” enough that he decided to switch sides.

His specialty is not in humanizing the appeals process as much as gaming it. Instead of challenging what he calls the system’s “fictitious” framework, he focuses on establishing that the judge or vocational expert has made a technical mistake. “Even though the current system is a lie and a fantasy and based on nothing,” he says, “you can force your client to win if you know what you’re doing.”

Reversing a denial of benefits can take years, even for an experienced lawyer. A 2014 study found that more than 60 percent of claimants denied at the hearing level were eventually awarded benefits. That’s partly because people’s disabilities often get worse over time, but also because the government is so hard to convince—that skepticism is predicated on assuring that taxpayer money goes where it’s deserved, with the expectation that well-intentioned experts, fluent in the language of bureaucracy, will make the decision. When that ideal breaks down, people like Diaz end up lost in an interminable nightmare of what looks an awful lot like bureaucratic evasion and nonsense.

Diaz only started getting his full monthly disability checks in 2020, 12 years after his accident. By then, he and his wife were divorced. He says the stress of his battles with the SSA, even more than the couple’s financial troubles, drove them apart. And the fight is still not over. The agency miscalculated his payments, gave him too much, and has now stopped his monthly checks until the difference is made up in early 2023. Diaz wouldn’t wish the disability program on anyone. “You think that when you become disabled, it’s there for you,” he told me. “And it’s not. It’s all a game.”