Nicolas Tucat/Getty

Dr. Seema Yasmin grew up, as she describes it, in a “family of conspiracy theorists.” As the daughter of immigrants living in England, the doctor-turned-journalist recalls, for instance, entertaining some outlandish beliefs about the British Royal Family. One book she and her cousins read and reread “told us that the Queen of England was a reptile in human form,” Yasmin writes in her 2021 book, Viral BS: Medical Myths and Why We Fall for Them. “A cassette tape we played over and over said Prince Charles was a shapeshifter who feasted on newborn babies. We lapped it up, our eyes wide with fear and wonder.”

While these tales may sound absurd, there’s a good reason they stuck. As her own family was deeply aware, the truth about the British Empire is equally absurd: England, an island country the size of Wyoming, has invaded an estimated 90 percent of the world’s countries (the United States, meanwhile, has invaded 80 percent). It gained its power by enslaving, killing, and starving people elsewhere, including India, her parents’ birthplace. “That in itself was a conspiracy,” she tells me. “But it’s very much true, right?”

On top of that, her family endured racism and xenophobia while in England. So when she heard unsavory narratives about the Royal Family, it was easy to listen; the tales provided her community with a sense of collective belief and belonging.

Yasmin would go on to become a doctor, and in 2011 took a position as a “disease detective” for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Epidemic Intelligence Service. Now she’s an author and professor at Stanford University who has written extensively about how false information goes viral and how to combat it, which she calls “the problem of our time.” And while she doesn’t believe in baby-eating reptilian shapeshifters, her upbringing has given her a refreshingly empathetic view of people who do believe in falsehoods. “It’s not hard for me to do that because I was that kid,” she says.

Now, with her latest book, What the Fact? (on sale September 20), Yasmin aims to equip young people to be better defenders against the spread of lies. Society has done teens a disservice, she says, by telling them to be cautious of fake news—without “arming them with the tools to be critical thinkers, spot the lies a mile away, and immunize themselves against falsehoods.”

I called Yasmin last week to discuss how fighting disinformation is like fighting Covid (or any viral disease, for that matter), what drives people on the internet to create “copypasta,” and whether the pandemic has made people more (or less) immunized against false information on the internet. An edited and condensed version of our discussion is below:

At the beginning of the book, you address the reader as a “free thinker.” The opening line states, “This book is not going to tell you what to think.” Why was it important to say that?

I’ve been working and doing research in the misinformation and disinformation space for over a decade. And it feels like everyone outside of the space thinks they’re not the people that will be fooled. But all of us inside that research space recognize that at any moment, we could fall for a lie. I wrote the book with that in mind. Like, “Hey 12 year old. Hey, 16 year old. I know you’re super smart. And I know you think you’re a free thinker. But I don’t know if you’re as much of a free thinker as you might want to believe.” So it’s kind of like ribbing people a little bit and poking fun at our pride and our wanting to believe that, Well, everyone else has biases. I don’t really think I have that many or any at all. It’s a reality check.

Aside from filling the need to have a book like this out there, are there other reasons why you decided to focus on young audiences?

What the Fact? is very much written in a way that’s accessible for everyone. But I thought it was especially important to have a resource for young people so that perhaps this book is a tool for, say, not having another January 6 insurrection. Maybe this book is the tool we need to make us all more resilient and protected against viral lies. I think young people are super smart and super aware. And when they have those tools that equip them with knowledge of why lies go viral while the truth sits lonely and quiet in the corner, then they’re actually one of our best defenses against information warfare, propaganda, and dangerous disinformation.

You write that fighting disinformation is a lot like fighting a virus. Can you talk more about that?

My mind was blown when I went from being an epidemiologist who tracked the spread of infection, to being a communications researcher, tracking the spread of lies about vaccines. I had been trained on how to use these mathematical models to predict in one month’s time, for example, where will infection X have spread to? How many people might have been infected or killed? Then when I went into studying how tweets and rumors and conspiracy theories spread, I learned that my colleagues in the communications field were using the exact same mathematical model that I had used to study the spread of a virus. There are so many parallels, including super-spreaders of infection—and super-spreaders of a viral tweet.

I think [the virus metaphor] is also a way also of helping our brains grapple with something that’s so broad and so big. Belief is a bit more abstract than “Oh, Covid spread from here to here. Now, this many people are sick.” I’m trying to get readers to think about how many people might be infected with a lie and how that might impact their behavior. How might that lie that spread from person to person to person? And unlike an infection, a lie can spread across a continent without one person even stepping foot out of their house.

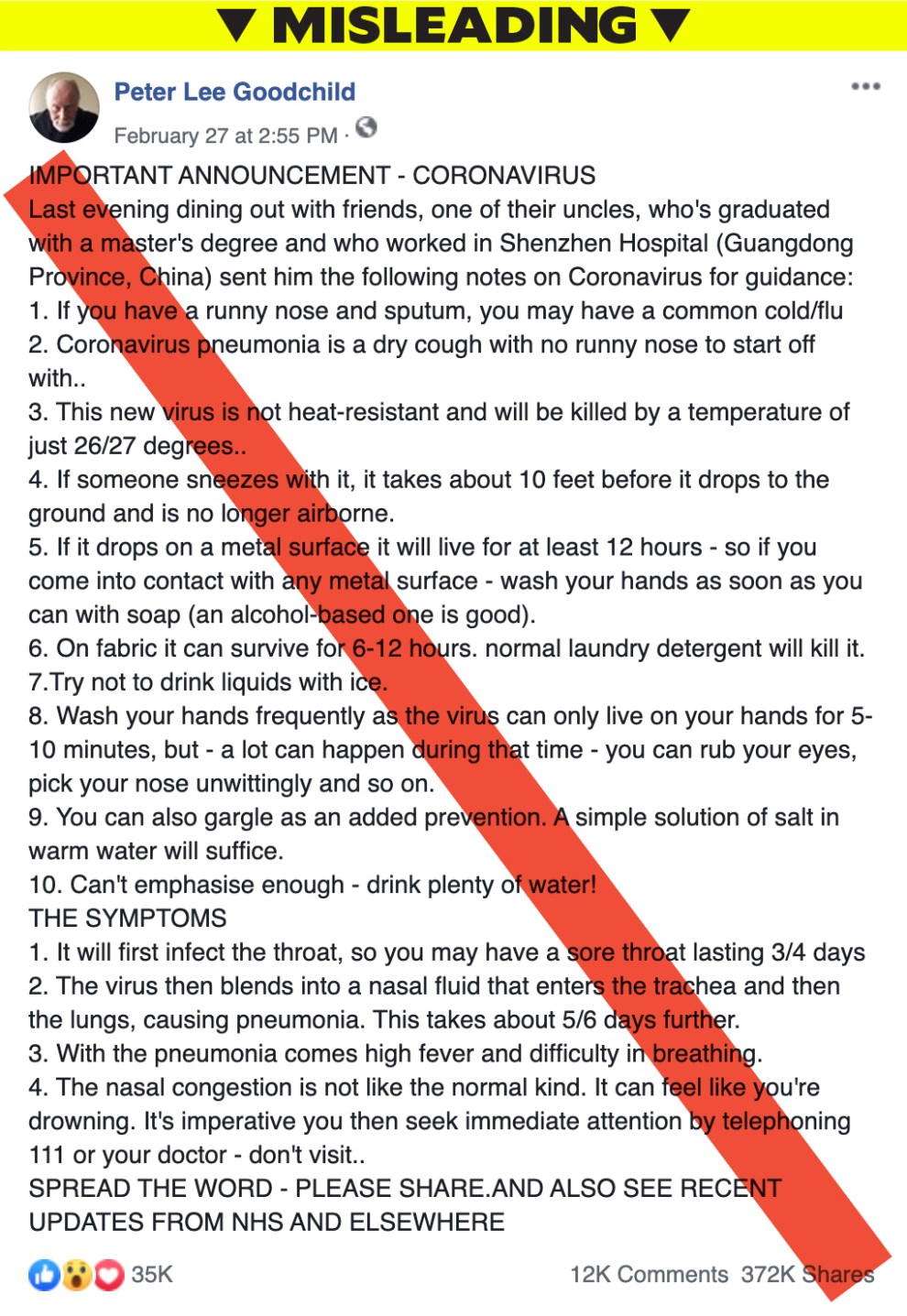

There is one example of this that you give in the book: a Facebook post about the coronavirus from Peter Lee Goodchild in February of 2020. Why did you choose that example?

I was spoilt for choice when it comes to examples of viral lies or things that started off with a hint of truth and then snowballed into complete bunk. And with that particular example, it was helpful that the BBC had done some really great reporting on him and that post. They track him down. And he was like, “Oh, I didn’t mean to do any harm. I was just trying to help people.” And that’s really realistic. That’s often how a lot of these things start out.

“Copypasta”: It’s this idea that you copy and paste, but you’re adding your own twist to a thing that you’ve seen. So it comes across as more credible. But you’re tweaking it—it’s mutating the message in the same way that viruses mutate and make them maybe more easy to transmit and quicker to infect people. And so that message that started off with Peter then took on different Facebook users’ names. It looked like they had typed it for themselves. Eventually, they added a different attribution and said all this information came from doctors at Stanford. And so it was making the point for me of how these things spread and how they change over time. That’s why they become so believable.

This post contains false and misleading information about the then-novel coronavirus. It was shared thousands of times, eventually morphing into a message that appeared to be coming from “Stanford University.”

Do you have any sense of why people on the internet would do that? Copy and paste the exact words, but just change a few details to make it look like it’s coming directly from them or someone more credible?

Psychologists have studied this extensively. There’s this idea that I want to be helpful, there’s a new infection spreading, and I want to put something in my Facebook post, I want you to think it came from me. There are status points, or social points, associated with being the first to—or seemingly one of the earliest—to share information.

And often, things go viral during times of uncertainty and crisis. In the early days of Covid, we didn’t know exactly what could protect against infection. We didn’t know how long the virus would last on certain surfaces. Then you come across a post where someone’s convinced that they do know the answer, and you want to believe them because you want some of that certainty.

Do you think the pandemic has changed people’s ability to identify good and bad information on the internet? Are we more aware now than we were two years ago or less?

I think there’s more conversation about the presence of fake news. I think people are more familiar with terms like “misinformation” and “disinformation.” But I don’t think we’ve done a good job of telling people how to protect themselves or why things go viral, or how they can stop a lie from spreading. So I think there’s more familiarity with the problem and the concept, but not so much around solutions. It’s just frustrating because there are solutions.

If you had to give two or three tips, how can people identify misinformation and disinformation online?

There are definitely some red flags to look out for. One is the information feels brand spanking new. That should set off your alarm bells, because why haven’t you seen it somewhere else? And it might be that it’s legit. And it’s just breaking news. But you want to check that what you’re seeing is brand new. Is it being reported elsewhere? Is it being reported in credible outlets? Or is it just exploiting our interest in things that are new and that no one else has seen?

And, second, if you come across something that triggers deep emotions in you, that’s a warning sign. Because lies are often packaged to be emotionally triggering. And sure, sometimes the real news is heartbreaking. It’s disgusting. But very often, bad actors trying to spread disinformation will do it by ceding panic and fear.

Third is, be extra cautious during times of crisis. And that could just be breaking news about a mass shooting. There’s so much uncertainty in that time. You’ll be seeing conflicting news reports, so be extra wary about hitting “retweet” or hitting “repost.” I remember even covering a mass shooting in Dallas when I worked at the Dallas Morning News. And we had to print corrections because the intel we were getting from the police was wrong. Because you know what a breaking news situation is like—they were getting their numbers wrong. We would report what the Dallas Police Department said, they would correct it, and we’d have to correct it. It’s just a whole whirlwind of information circulating at times like that and you have to be wary.

And if I could add one more point, I’d say it’s not just text being used to spread lies; viral images are often used to push harmful narratives. We need to be more diligent about fact-checking video and pictures.

One photo you point to in What the Fact? is the famous, “Muslim Woman on Westminster Bridge.” That example was interesting because it’s not a fake image, it was just taken extremely out of context.

Yes—that photo is based on a vicious attack that took place on Westminster Bridge in Central London, where people were stabbed. And very soon after the attack, there was a photo taken of a visibly Muslim woman. She’s wearing a headscarf. She’s on her phone. She’s on the bridge. And I think she looks distraught in that picture, but for many, the way it was framed was, “Here’s a woman who’s Muslim and she’s just walking past the body of someone who’s just been attacked.”

And actually, that wasn’t true. She helped somebody get out of the situation. She was on the phone with her family who was really worried about her because they’d heard about the attack. There’s all this context and information behind the picture. But this one snapshot was being used to support a narrative that Muslims are terrorists or that Muslim support terrorism.

So in a situation like that, there are a couple of things you want to do. One, if you’re seeing this Islamophobic narrative being pushed, you want to see who’s pushing it. What was the origin of the story that this woman is heartless? And then you also want to check if that image is accurate, and look for other images that were captured at that time. And once you find those, you’ll get a fuller picture of what was really happening.

The "Muslim woman on Westminster bridge" has spoken out regarding reaction to her photo https://t.co/GUynNzH0fb pic.twitter.com/NbblAwRjrQ

— BuzzFeed News (@BuzzFeedNews) March 24, 2017

You’ve said that countering false information is “the problem of our time.” Are there any big misinformation battlegrounds that you see in the near future? Vaccines? Ukraine? Are there other areas that are charged right now?

We can list topics like climate change, anti-science sentiments, democracy and elections. Abortion misinformation is rife right now. Disease-specific misinformation. However, I would say it’s even broader and bigger than that: Our very notion of, What is a fact? What is the truth? is being shaken up.