As I was watching the new Hulu adaptation of Sally Rooney’s 2017 novel, Conversations With Friends, I kept waiting for something to happen that was never going to happen. The show follows two young women in Dublin, Frances and Bobbi, who become romantically entangled with an older married couple. As the series progressed, I was waiting for Bobbi—the lesbian secondary character to the bisexual main character, Frances—to have her own storyline, one that doesn’t revolve around Frances or Frances’ troubled relationship with a man. I knew this would not happen because I’d read the book. But that didn’t keep me from hoping.

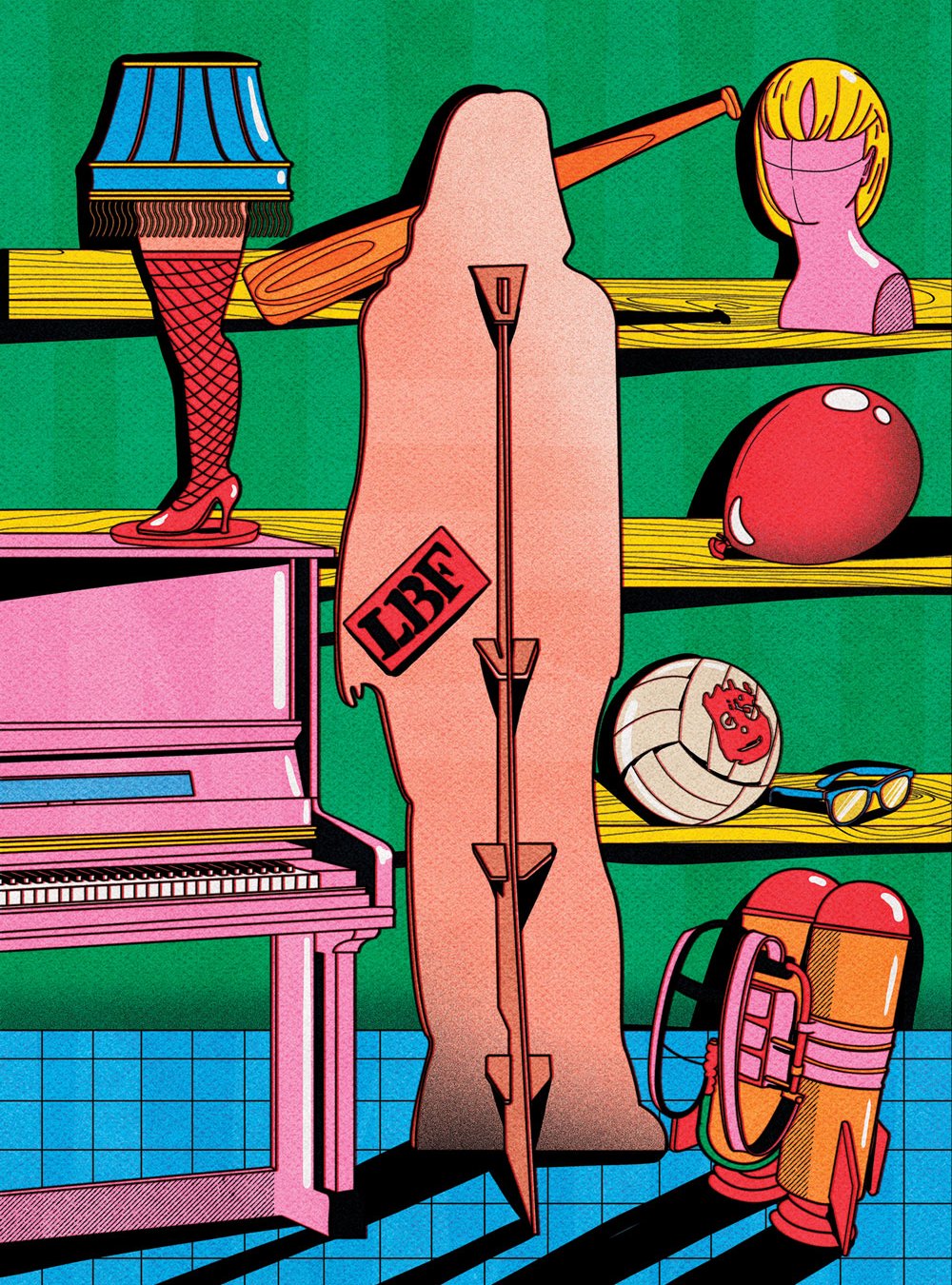

Bobbi is just the latest iteration of a burgeoning trope in film, TV, and contemporary literature: the Lesbian Best Friend. The LBF is always the sidekick of a straight (or occasionally bisexual) female protagonist. Though these characters began cropping up in the early 2000s, we have seen an explosion of them in the past 10 years. It’s a trend that, on the surface, might seem like progress. But ultimately, the trope does more harm than good, reinforcing the idea that queer storylines are only legitimate when they’re in close proximity to straight ones.

The typical LBF is a fun, adventurous, and somewhat larger-than-life caricature. If her queerness is mentioned explicitly, it’s of little or no significance to the central drama. For instance, in Younger, a Darren Star TV series about the publishing industry, Lesbian Best Friend Maggie mostly appears to offer unhinged advice to protagonist Liza about her various professional dilemmas. Sometimes the LBF is clearly queer-coded in appearance and mannerisms, but the story is strangely evasive on this point, denying the character a love life, as in the case of butch suspender-wearing Susie in the Amazon Prime comedy-drama The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel and boardshorts-clad Eden in the 2002 surf film Blue Crush.

Even when these stories allow some scenes of the LBF absent her straight counterpart, the defining aspect of the LBF’s character is always her relationship to a straight woman. The story is never about the LBF; it is never hers to tell.

So how did we get all these flattened, second-fiddle renditions of queer women in our popular culture? The Lesbian Best Friend is, to some extent, a variation on the well-documented Gay Best Friend trope, a harmful stereotype of a gay man who exists in a narrative for heterosexual amusement without any real agency, nuance, or development. “The Gay Best Friend character serves the function of being titillating, being a little raunchy, saying all the things that the main character wants to say but doesn’t get to,” says Hollis Griffin, an associate professor of communications and media at the University of Michigan specializing in queer media studies. “These characters are for comic relief, or they are a way to outsource all sexual references, to make sexuality safe by putting it on ‘the Other.’ The gay character functions as the Id, becoming the repository for all the main character’s deepest wants.”

It perhaps makes sense that in recent years, when Hollywood has finally begun to respond to our hunger for women-led stories, especially those exploring relationships with other women, we’d see the Gay Best Friend trope morph into its female analog.

Arguably the most high-profile example of the LBF character in the past year has been Bobbi in Conversations With Friends. In both Rooney’s novel and the TV series, Bobbi and Frances are best friends, ex-lovers, and roommates who perform spoken-word poems together. But after Frances begins an affair with a married man, the focus of the series shifts toward Frances’ relationship with him. Bobbi and Frances’ friendship ruptures and repairs, and they briefly start sleeping together again. But mostly, Conversations With Friends treats Bobbi as a device to more fully explore Frances. “She’s the writer,” Bobbi says at one point when introducing Frances. “I’m like, her muse.”

Bobbi is a vital artistic and social collaborator without whom Frances’ artistic achievement and emotional breakthroughs would not be possible. (This is true in other LBF media too; in Younger, The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, and Blue Crush, the LBF encourages the main character’s career dream to be a book editor, a stand-up comedian, and a professional surfer, respectively, and calls the protagonist out on behavior that distracts her from her dream.) When Frances writes a short story about Bobbi without her consent, it is Bobbi who compels Frances to confront her self-absorption, precipitating Frances’ breakdown and eventual redemption. “I don’t think you think anyone else is real, Frances,” Bobbi says, forcing Frances to confront essential truths about herself. But Bobbi’s own artistic aspirations, relationships, and family troubles are left mostly unexplored.

In Conversations With Friends, Bobbi (right) plays the role of Lesbian Best Friend to Frances (left).

Enda Bowe/Hulu

Frances is ostensibly bisexual, but as Natalie Adler wrote for Lux Magazine, for Rooney’s characters, “bisexuality operates as a hypothetical, rather than an actual desire: one that might complicate her character’s dilemmas or provoke tension but never materializes as a valid choice for living.”

Frances and Bobbi’s arc is fairly typical of LBF stories: In many, the main character prioritizes love with a man over the connection she has with the LBF—and if the LBF objects, she’s painted as immature and unreasonable. In the 2014 romantic comedy film Life Partners, type-A lawyer Paige and her precariously employed LBF, Sasha, sleep in each other’s beds, go out and get drunk together, and engage in absurd pre-choreographed public fights. But the friendship between the two women becomes less important in the second half of the narrative, when Paige meets a handsome doctor named Tim, and eventually gets engaged. After Sasha protests the loss of their friendship, Paige accuses her of being unwilling to grow up: “You’re going to wake up one day, and you’re going to be 35, and you’re going to have no relationship, you’re going to have no savings,” she says. “All your friends are going to be married with kids and be miles ahead of you.” The film’s message is clear: Friendships between women belong in childhood, while marriage with a man is the inevitable, superior future.

It’s not just Sasha who is depicted as a poor slacker, living outside of capitalism, or just kind of a mess; many LBFs are drawn this way. While the Gay Best Friend is frequently portrayed as affluent, socially stable, and popular, the Lesbian Best Friend is often professionally unstable or unemployed.

“There’s a history of representing queerness in conventional film and television as gender inversion, the idea that if a character is given characteristics of the ‘opposite gender’ the audience will read them as queer,” Griffin says, drawing on the seminal 1981 queer media text, The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies, by Vito Russo. “So this appears as class association too. Queer men get coded as rich because there’s a way in which financial luxury dovetails with notions of excess, which is seen as feminine. Making queer women sort of rough and tumble is supposed to read as masculine. ‘Oh, she’s unemployed, living out of her car?’ It’s because she’s sort of a bro.” The LBF’s role is to show the straight main character a kind of crazy, scary womanhood that she does not want, one that ultimately pushes her back onto the proper path.

The LBF story may not be all bad, in that it depicts a real tension that can happen between straight women and queer women. But we never get to see these feelings from the queer woman’s perspective, to understand what it might feel like to fear you are losing your most primary and significant relationship. A queer life that does not center a man is never considered a valid place for a woman to end up. Why is the lens of our story still so often trained on straightness when the queer character’s story can be so much richer and more innovative?

Griffin has a straightforward answer: “Viewers still aren’t imagined to be queer,” he says. “Most media is just not made for that audience. Things are changing, but by and large, they are still made for a straight viewership.” In 1975, the film theorist Laura Mulvey famously coined the term “the male gaze” to describe the way films often assume a male vantage point. The persistence of the LBF trope today might be described as a result of the straight gaze.

In the past few years, the sheer number of LGBTQ characters onscreen has increased substantially. But there’s little evidence that these characters are getting greater depth and complexity. A recent GLAAD report found that while 18.2 percent of major studio films included characters that were LGBTQ, only 9 percent included a queer character who had more than 10 minutes of screen time. The majority of LGBTQ characters were onscreen for less than three minutes.

Despite these dispiriting numbers, the audience for complex stories about queer women and gender nonconforming characters is only growing. The world is getting queerer, and young women are getting much queerer. According to a Gallup poll, one in five Gen Z adults identify as queer, and the vast majority of this group are not men. And according to a Nielsen report, queer people tend to watch more television than straight people and are much more likely to be actively talking about it on social media. A 2019 report from the Protein Agency, a global brand consultancy, also shows that Gen Zers “are seeking intimacy in their friendships” more than other generations.

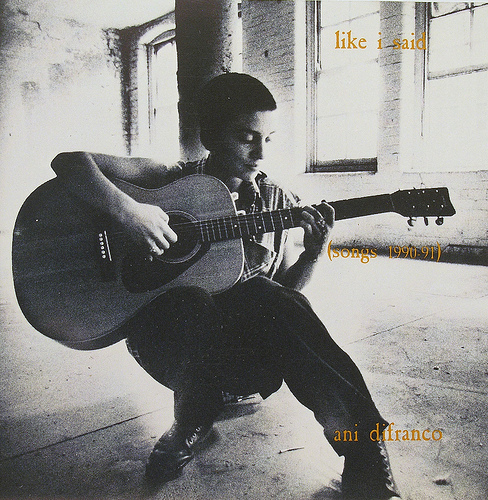

Thankfully, some new projects are exploring cross-sexuality female friendships from the queer side. In literature, A Song for You, a 2019 memoir by Whitney Houston’s longtime best friend and ex-lover Robyn Crawford, and So Happy for You, a 2022 novel by Celia Laskey, dive deeply into the psychology of queer women.

The recent television reboot of A League of Their Own features Max, a queer Black lesbian who is best friends with a straight married woman named Clance. We watch as Max pursues her dream of playing baseball in the professional women’s league, finds queer romance, reconnects with her trans uncle, Bertie, and struggles, fails, then finally succeeds in coming out to Clance, who accepts her. Rather than centering Clance’s story, the show subverts the LBF trope by positioning Clance as Max’s cheerleader and supporter.

“I’ll be back in the spring,” Max says before she boards a bus to start touring with her new baseball team. “As soon as I’m done.”

“No, you won’t, Max,” Clance says. “This is going to lead you somewhere, and that’s going to lead you somewhere else. This is the start of everything, and I’m so happy for you.”

“We really wanted…to focus on the stories that weren’t told in the [original 1992 A League of Their Own] film,” Abbi Jacobson, one of the show’s co-creators, and herself a queer woman, told Them. “A lot of those were queer stories.”

Identity-based representation is important, but it’s just the first step. We need more stories approached from a queer gaze, rather than a straight one, to allow viewers and readers the truly transformational experience that good art featuring queer characters can supply.

“The queer gaze is a combination of a queer perspective and a powerful kind of fantasy that exposes how little queer culture has existed historically in popular culture,” says University of Southern California professor and cultural critic Karen Tongson. “We never ask straight people how they know a piece of media is for them. It’s a presumptive sense that takes their way of being and existing for granted. That’s what the queer gaze does for queer people.”