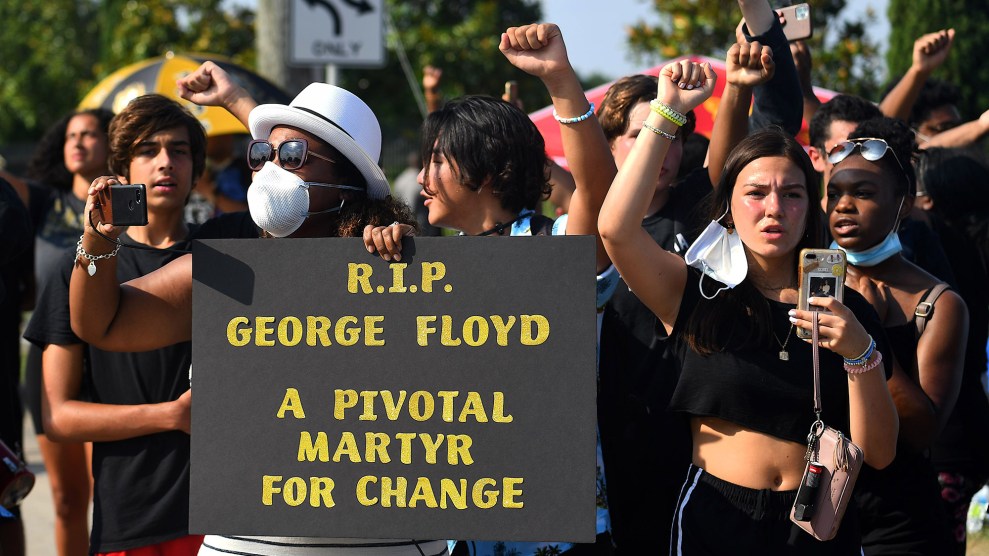

Mourners watch the funeral procession of George Floyd in Houston on June 9.Johannes Eisele/Getty

Michael Brown’s death at the hands of a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014 sparked nationwide protests and jumpstarted the Black Lives Matter movement. His death also opened a conversation about the startling lack of good data on how often police use force and on whom. Nearly six years later, amid a massive new wave of activism, it’s become apparent that we have a long way to go toward fully quantifying the human toll of police violence. More bluntly: Does George Floyd’s death count?

In 2015, then FBI-Director James Comey noted that there was better data on movie ticket sales than the use of force by cops. “It’s embarrassing and ridiculous—that we can’t talk about crime in the same way, especially in the high-stakes incidents when your officers have to use force,” he said. While there is more data now than there was then, it remains incomplete and uncentralized. At a US Commission on Civil Rights hearing in 2018, Geoffrey Alpert, a criminologist and professor at the University of South Carolina, called the lack of federal data on the use of force by police a “national embarrassment.”

The practical challenge is undeniable: With 18,000 police departments across the country, collecting meaningful data from all them is a gargantuan task that requires immense human resources to obtain, verify, analyze, and visualize data, and hardware infrastructure to host and maintain the data.

The Center for Disease Control’s National Vital Statistics System and the Federal Bureau of Investigations’ Uniform Crime Reporting program and both log police killings, but their data are known to be incomplete. CDC’s database reported 539 deaths from “legal intervention” involving a firearm discharge in 2018. This is an undercount, since other sources have recorded many more deaths by police shootings. And this count does not include people who were not killed by gunshots, such as Floyd, who died after a police officer restrained him with a knee on his neck.

The FBI’s database records “justifiable homicides” of “felons” by police, a flawed metric since what counts as justifiable is defined by police departments and the definition of a felon in this case isn’t someone who has been convicted of a felony, but rather someone who is perceived to be committing felony act at the time of their death. The FBI recorded 410 “justifiable homicides” by police officers in 2018. It is possible that Floyd, who was killed after officers suspected him of committing forgery by passing a $20 counterfeit bill, could counted as a “felon” in this database?

In the absence of reliable, complete federal data on the use of force, the task has been picked up by journalists, advocates, academics, and citizens. One of the most comprehensive, easy to use, and well-maintained data sources on police shootings the Washington Post‘s database, which its reporters built after Brown was killed. It has documented twice as many killings as the FBI or CDC databases. According to its count, since 2014, nearly 5,000 people have been fatally shot by police officers; a third of them were Black. Black people are killed at more than twice the rate as white Americans, according to the Post. But since this database only counts shootings by officers, Floyd or Eric Garner, who were both killed by chokeholds, would not be included in its data.

The Guardian published comprehensive data on fatalities caused by police use of force (including shootings) for 2015 and 2016 but has stopped since then. At a Department of Justice’s summit on violent crime reduction in 2015, Comey said, “It is unacceptable that the Washington Post and the Guardian newspaper from the UK are becoming the lead source of information about violent encounters between police and civilians. That is not good for anybody.”

Another detailed data source is Mapping Police Violence, created by data scientist Samuel Siyangwe and activist Deray McKesson. It tracks data based on news reports and three crowdsourced databases: FatalEncounters.org, the US Police Shootings Database, and KilledbyPolice.net. It counts the deaths of people who die by any means used by police and also describes the circumstances that lead to the deadly use of force against them. But it still may not be a complete count since it doesn’t pick up deaths that aren’t mentioned in the media.

These databases only count people who are killed by police. There remains little data on instances where police use force and the victims are hurt or otherwise harmed but do not die. New Jersey Advance Media collected every instance of use of force by police officers from every police department in the state over five years. It’s a rare dataset that not only collects deaths by use of force, but also injuries. Moreover, the oldest data from all of these databases only goes back to 2013. For researchers to meaningfully analyze trends in police violence, they say they need data that goes back further and has more detail.

“I want to know the decision to shoot. That’s what’s most important. Why did the officer decide to use deadly force?” says Alpert. “We know there’s some issues with racial disparities, but there are a lot of things about the situation we don’t know. And that’s where we’ve got to get good data. We’ve got to understand when force is used, how force is used and then we can start to go about fixing it. “

Last year, the FBI finally announced that it would start collecting comprehensive data on police violence. This new database would not only count police shootings but also “serious bodily injury” caused by the use of force. It would also count and the number of shots fired by a police officer in the direction of a civilian, even if the shots miss. But only 40 percent of the police departments nationwide are reported to have volunteered to share data and contribute to the initiative. In contrast, 18,000 local law enforcement agencies (nearly all of them), contribute to FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting system, which collects detailed crime statistics.

Researchers say this initiative should have come much sooner. In 1994, in the aftermath of the Rodney King protests in Los Angeles, Congress gave the Department of Justice the authority to sue police departments for unconstitutional practices. It also gave the attorney general’s office authority to collect data on police misconduct and use of force from law enforcement agencies from all over the country.

Joanna Schwartz, a professor of law at the University of California Los Angeles, says the department never fully exercised its authority to compel police to turn over this data. “They essentially asked local law enforcement to produce information and there was never any consequence for agencies that that didn’t work with the attorney general’s office on these efforts,” she says. “The attorney general’s office had this power for 25 years and not used it.” She says that Congress should take matters into its own hands and fix this problem.

Local police agencies collect detailed use of force data, but many resist sharing it, Alpert says. Both Alpert and Schwartz say the only way to get them to be more transparent by mandating data collection and sharing as a condition for receiving federal funding. For example, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has excellent data because state transportation departments have to agree to collect data in return for federal funding.

“The notion that you can’t manage what you don’t measure has been something that has been a foundational concept in law enforcement,” Schwartz says. Police departments already use COMPSTAT, software that tracks crime hotspots and arrest rates. Similarly, there should be data to “track hotspots in police accountability,” she said.

Of course, whether or not it appears in any of the existing databases, George Floyd’s death will count. As his memory fuels the campaign to change American policing, it should also help change the way we record and remember all those who have died or been injured under similar circumstances.