The Monument

After the Civil War, Edward Virginius Valentine returned from Europe to his hometown of Richmond, Virginia—the former Confederate capital—and began using his training in classical sculpture to enshrine the myth of the Lost Cause. Over the next few decades Valentine made a career of sculpting monuments to defenders of slavery, building tributes to Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, among others. And he made the statue of Confederate President Jefferson Davis in Richmond—unveiled on Monument Avenue in June 1907 by Davis’ last remaining child and toppled in June 2020 by protesters against systemic racism after the death of George Floyd.

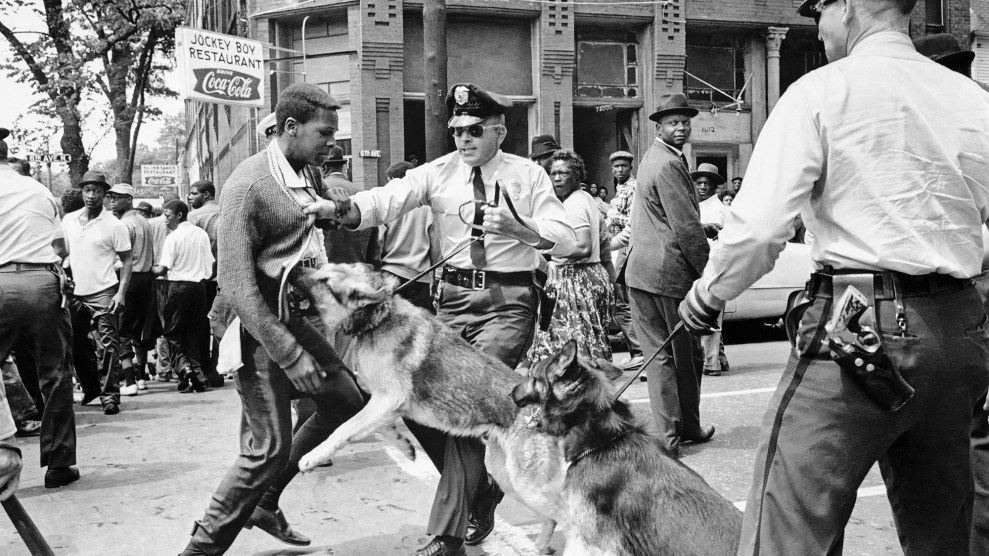

Over the past few months, protesters have spray-painted, damaged, torched, and toppled symbols of white supremacy around the country. Critics have decried the acts as shameful attempts to erase the country’s history. The president demanded that protesters who took down a Confederate monument in Washington, DC, be “immediately arrested.” But the destruction of our cultural legacies is itself part of our cultural legacy, reaching back to ancient history. It is as old as the act of honoring false gods.

The Symbolism

Valentine, working with an architect, made the monument “overwhelmingly tall” and depicted Davis in a “heroic” pose, delivering his famous 1861 speech about quitting the US Senate to the join the Confederacy. Like all the Confederate statues on Monument Avenue, it was erected during an era when white Southerners were rewriting the story of the Civil War. According to the propaganda of the Lost Cause, the Confederates hadn’t betrayed their country; they’d fought gallantly for the principle of states’ rights. And Davis wasn’t the treacherous leader of a failed state that had rebelled to protect slavery; he was a hero fighting a tyrant in vain to protect a “way of life.” But how to show all that? Valentine, and other artists, looked to a previous empire: Rome.

Behind Davis is semicircle of Doric columns, like those used in the Colosseum and the Parthenon. An angelic female figure hovers above him, intended to be an allegorical figure of the South, harkening back to the classical images of gods. This is purposeful. As public historian Lyra Monteiro explains in her forthcoming book on the invention of “white heritage” in the early United States, the white landowners of this time saw the Greeks and Romans as their racial ancestors. W.E.B. Du Bois notes in Black Reconstruction that planters “threw Latin phrases” into their speech to cultivate an air of gentility, an affectation that reached a grim pinnacle with John Wilkes Booth supposedly yelling “sic semper tyrannis” after shooting President Lincoln.

More importantly, Rome’s own history of slavery was central to the defense of American chattel slavery. In his famed Notes on the State of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson is at pains to distinguish between the “white” slaves of antiquity and the enslaved Africans in the Americas. The ancient slaves went on to become great artists and scientists due to the inherent characteristics of their race, Jefferson argues. The inferior Black souls that built and toiled on his Monticello—including, presumably, his own progeny—would never reach such heights. “The past,” Monteiro writes, “becomes an important proving ground to verify the immutability of racial categories, and the inevitability of the hierarchical structure of contemporary society.”

Art was joined to the effort to create a racial and cultural identity out of some imagined classical patrimony. American sculptors traveled to Europe to study the ancient Greek statuary that scientists like Johann Friedrich Blumenbach were using to define the normative white body in their “empirical” racial hierarchical system. Valentine’s own masterpiece was the sculpture Andromache and Astyanax, depicting an incident in The Iliad. This was the heyday of Neoclassicism. An elegant vision of history was summoned to prettify a brutish present. “The ‘classical’ generally is what gets created to explain what whiteness is, and that’s why it happens at the same time as colonization,” Monteiro says. “It’s to justify why they are who they are.”

Inscribed in the very design of the Jefferson Davis monument was the project of rationalizing the racial order.

Library of Congress

Chip Somodevilla/Getty

The Iconoclasm

The ritualistic destruction of statues that some find sacred isn’t new, nor was it always considered barbaric. In antiquity, most of the great Mesopotamian, Persian, and Greek civilizations routinely destroyed the art and architecture of their enemies during war, a symbolic act of regime change. “Castrating a statue of a king showed that he will no longer have heirs,” explains Bailey Barnard, a doctoral student in ancient Greek art at Columbia University, who specializes in the history of iconoclasm. “Hacking out the eyes and ears of a king meant that he couldn’t see his people.” In 612 BCE, conquering Babylonians rubbed away the faces of Assyrian kings depicted on stone reliefs.

In 480 BCE, when the Persians ransacked the Acropolis, the Athenians coped with their defeat by turning ritualistic iconoclasm into a way of demarcating the civilized from the savage. “[S]uch iconoclastic activity came to be seen as a paradigmatic example of ‘Oriental’ impiety and violence,” writes art historian Rachel Kousser. The stereotype was cemented in the art of the Parthenon, where images of ransacking Persians sat atop the columns. Says Barnard: “This set up the East-West dichotomy of civilized, not-iconoclastic people against Eastern barbaric, iconoclastic people.” Looters, you might say. Thugs.

The Anglo-Western “descendants” of classical antiquity inherited the values around the preservation and destruction of art. In the so-called Age of Enlightenment, museums, populated with collections from ancient Greece and Rome, sprouted up as slavery spread throughout the New World. These were sites of preservation and celebration, redoubts of “civilization” built to contrast with the “savagery” without.

The masses weren’t always pleased with the public art in their cities. In July 1776, a group of radical agitators—sorry, revolutionaries—called the Sons of Freedom pulled down a statue of King George III in New York, beheaded it, and melted down the body for bullets. The outcry in Europe was swift. One scandalized British officer sent the statue’s head to back to England as proof of the “infamous disposition of the ungrateful people of this distressed country.” According to a political cartoon of the event drawn by a German artist, the ungrateful and distressed people ripping down King George were none other than enslaved Africans. It was an early instance of homegrown iconoclasm, then as now decried by the ruling class.

Parker Michels-Boyce / AFP /Getty

The System

In Belgium, people are forcing down statues of King Leopold II, acknowledging the atrocities he committed in the colonial Congo. In California, statues of Saint Junipero Serra, who founded the mission system there that led to the enslavement and displacement of Indigenous peoples, are being toppled. Monuments to Christopher Columbus, that harbinger of New World colonialism, are coming down, too. Blows are being struck against tokens of white supremacy around the world.

But iconoclasm can be a tricky thing in a country still grounded in the principles of the Enlightenment. In San Francisco, a statue of Ulysses S. Grant was torn down, as was a statue of abolitionist Hans Christian Heg in Madison, Wisconsin. Sympathetic liberals thought this was going too far, but they were missing the larger reckoning underway. “We’re basically populating our landscapes with able-bodied white men on pedestals. It almost doesn’t even matter who they are,” Monteiro points out. “It’s a message of ‘I am in power, and you are not.’” It is white supremacy, too, to center the heroism of Grant and Heg at the expense of the enslaved people who were the principal agents of their own liberation. Pulling down monuments throws open the question not just of who gets celebrated but of who gets to decide, and how, and on whose behalf.

The plinths left behind by these felled monuments are a negative space daring us to fill them with something new. In some places, this is already beginning to happen. Just this week, in Bristol, England, a statue of Black Lives Matter activist Jen Reid went up where a statue of slaver Edward Colston had once stood. Importantly, it was a guerrilla installation, unapproved by the city. The aesthetics of the piece were still beholden to some of the old cultural frameworks—a heroic individual, towering over the group—but the transgression of putting it up at all sent its own message: The time has come for the unauthorized story. A day later city officials removed the statue.

The iconoclasm of the past few months is a war on the inevitability and immutability embodied by the monuments. The ease with which they have come down reminds us that whiteness itself is artificial and impermanent. Something made by humans can be brought down by humans, too. “Dismantling the statues is not erasing history,” Barnard says. “It’s an act that shows how we can dismantle a system.”