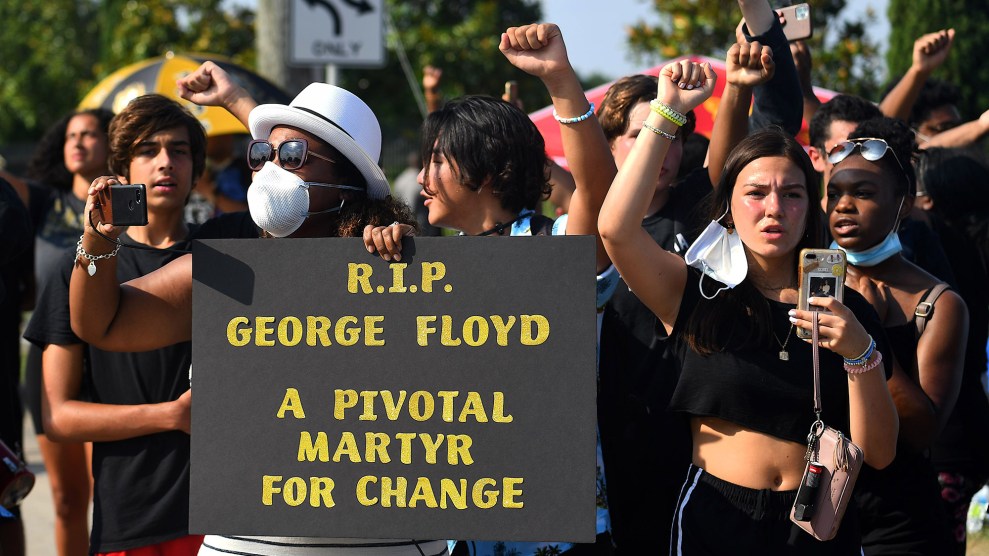

A memorial to Sean Monterrosa, George Floyd, and other victims of police violence is seen in Oakland, California, on June 8 ane Tyska/Digital First Media/East Bay Times via Getty Images

In 2009, shortly after police officers shot and killed her 16-year-old brother in San Pablo, California, Geoffrea Morris drove to a cemetery to look for a plot of land. On top of everything else, she was stressed about money: Burial and funeral expenses would cost tens of thousands of dollars, and she was strapped for cash after graduating from social work school. A man who worked at the cemetery asked whether her brother had been the victim of a violent crime—a designation that would allow him to give her a discount. She started to cry.

“They’re not seeing him as a victim,” she recalls telling him.

In California and many other states, crime victims and their family members can apply to the government to help pay for funeral costs, counseling, medical fees, or other crime-related expenses. But there’s a significant catch: Across the country, victims of police violence don’t qualify. Police departments won’t issue them reports certifying their victimhood, documentation that’s required by most states’ victim compensation boards. Plus, no state’s board will provide compensation to anyone whom officers suspected of being involved in a crime when they were injured or killed, which is often the case for people harmed by police. Morris’ brother, Leonard Bradley Jr., had been suspected of a carjacking when he was shot. Two officers chased him up a grassy hill to a fence, where they fired their weapons after he allegedly reached for his waist. He was unarmed. “Once the police is involved in a shooting, especially like in my brother’s case, you’re just seen as the perp, and there are no services for the family,” says Morris.

Just recently, though, it looked as if Morris might get some relief. The question of compensation for victims of police violence became an issue earlier this summer amid an urgent and sweeping debate about police reform following George Floyd’s killing by a police officer in Minneapolis. Morris, along with other victims’ families and criminal justice activists, hoped California would be the first state to overhaul the status quo with a bill that would have allowed victims of police violence and their family members to qualify for damages from a victim compensation board. But just last week, their hopes were dashed, as the proposal died in a Senate committee. “I’m devastated,” Morris told me upon hearing the news of the failed legislation.

“There’s nothing out here to help us families,” adds Michelle Monterrosa, 24, whose brother Sean Monterrosa, 22, was killed by a Vallejo police officer in June outside a Walgreens. The officer, responding to reports of looting during the protests sparked by Floyd’s death, fired five rounds through the window of an unmarked pickup truck at Sean, who had been kneeling on the ground outside the store; the officer said he mistook the hammer in Sean’s pocket for a gun.

After Sean died, the Monterrosas faced about $100,000 in funeral and burial expenses, far beyond what they could afford. The family lives together in a one-bedroom home in San Francisco, and Sean, a carpenter, had contributed a sizeable portion of their income. His mom works seven days a week as a caregiver for an elderly woman, and his dad runs a cafe. After his death, Michelle postponed a semester of school to handle the phone calls from journalists and work on police reform advocacy, and her sister Ashley, 20, quit her retail job to do the same. They both lobbied for the bill to make families like theirs eligible for compensation.

Under the proposed legislation, California’s victim compensation board would no longer have required people to file a police report to receive funds. Instead, families and survivors of police violence could have submitted to the board a note from a doctor or social worker certifying that the incident occurred. Crucially, the legislation stipulated they would still be eligible for funding even if their loved one was suspected of a crime. The bill, a version of which had passed the Assembly, was “California’s opportunity to demonstrate that we value the lives and experiences of all victims, and particularly Black and brown victims of police violence,” Assembly member Tim Grayson, one of the co-authors, said in early August. “Victims and their families should not be forced to turn to GoFundMe accounts to cover funeral, burial, and medical expenses,” added San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin, who supported the proposal.

“Everybody should be able to lay their family properly to rest,” says Morris. Whether the courts determine a police shooting was justified or not, she says, “the system took your loved one away—their grief is caused by government. The government should be held to a higher standard, even when it’s warranted, to support families of police violence.”

To pay for her brother’s funeral, Morris had to dig into her savings; she also asked friends and neighbors for donations. But there were other costs. The family still couldn’t afford therapy for her and some of her siblings, which would have been helpful not just immediately after the shooting, but for the months and years of ongoing trauma—like when their pro bono attorney dropped their wrongful death case a year later. And it was exhausting dealing with all the press inquiries. “You can’t even grieve because you’re on the news every second,” she says.

This is just one reason why family members and advocacy groups also want lawmakers to pass additional legislation that would allow more victims of violent crime, along with their family members, to take time off work or break their leases. Right now, these benefits are only afforded to survivors of sexual assault, human trafficking, and domestic violence. “Most of the statutes on record for crime victims in California are centered around the experiences of only certain types of crime victims,” says Tinisch Hollins, who leads the state chapter of Crime Survivors for Safety and Justice, a nonprofit that co-sponsored the compensation bill. “A lot of the advocacy has been led by organizations that are led by white women, people who do not reflect the voices of people in communities who experience crime and violence on a more consistent basis,” including gun violence and excessive police force.

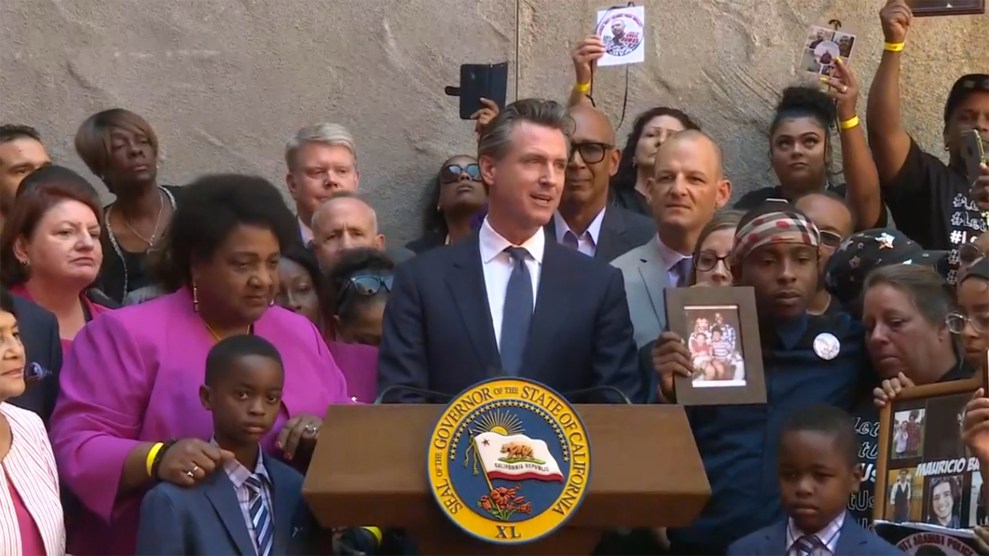

California state lawmakers, currently in the middle of a pandemic-shortened legislative session, are deciding the fate of more than a dozen police reform bills, including legislation that would ban the use of tear gas on crowds and require the state attorney general to review officer killings of unarmed people. Police reform advocates hope these proposals have better luck than the compensation bill, which died in the Senate appropriations committee on Thursday after the state’s victim compensation board warned lawmakers that broadening its payouts to police brutality victims could strain already-tight state budgets. (Some police chiefs also opposed the legislation.) The board estimated it could cost hundreds of millions of dollars each year to expand the pool of people making claims—a price tag based on the maximum payouts allowed, $70,000 per claim.

But Hollins suggests that tab may be vastly overinflated. The board is a payer of last resort, which means it only pays for expenses that aren’t already covered by other means, like health insurance, workers compensation insurance, and automobile insurance. In the 2019 fiscal year, 50,000-plus crime victims and family members filed for compensation. Over that period, the board’s average payout to eligible people was just $1,200 per claim, and the total payout to all crime victims was about $62 million. A recent agency analysis estimates that broadening the law to include victims of police violence might add about 1,000 claims annually. “We’re not talking about millions of folks—we’re talking about a smaller number of severely disenfranchised survivors,” Hollins says. “Someone was harmed, and how do we remove all the barriers to make sure that harm is addressed and the sanction is not passed on to their family members?” The compensation board declined a request for comment.

“We can defund the police to afford it,” counters Ashley Monterrosa. Without state help, she and her sister launched a GoFundMe for their brother’s funeral. But they feel the toll of his death in other ways. They say their mom is exhausted and has only gotten a few days off work to grieve. “It hits her hardest when she gets home at 4 p.m.—that’s when I see her cry every day,” says Michelle Monterrosa. “That’s around the time when Sean would come home from his job.” If the legislation had passed and they’d gotten compensation, maybe their parents could have stopped worrying about financial bills for long enough to try to process their son’s death. And maybe they could have paid for therapy; one of Ashley’s high school teachers is currently helping them crowd-source funds from the community so they can afford it.

Sean had recently finished carpentry school and dreamed of building the family a house so they could move out of the one-bedroom home. The last text message he sent to his sisters was at 11:49 p.m. on June 1, asking them to sign a petition to get justice for George Floyd. The sisters replied right away to say they’d signed, and each sent him a heart emoji. He was killed less than an hour later.