Residents at the Shore Towers Condominium in Astoria, New York, sing on the balcony to promote unity amid isolation measures.Ron Adar/Zuma

In late January, China’s president Xi Jinping ordered several cities to shut down in an attempt to quell the spread of a quickly moving respiratory infection we now know as the novel coronavirus. The quarantine soon included more than 50 million people. And the restrictions were stringent. The epicenter of the epidemic was in the large industrial city of Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province. In what essentially became one of history’s largest examples of a cordon sanitaire, a French term that refers to restricting people’s movement in and out of geographical areas, provincial authorities soon banned travel in private vehicles, foot police patrolled apartment complexes to keep residents indoors, and tech giants created live maps of cases using government-collected health data, prompting outcry from human rights experts.

Hubei province appears to have gotten a handle on the spread of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, in recent weeks, and some of the travel and work restrictions have eased up accordingly. And yet, as Yanzhong Huang, a senior fellow at the US Council on Foreign Relations, wrote, “China’s harsh, restrictive containment measures are not only non-replicable in most places. They probably should not be replicated.” The draconian measures have taken a heavy toll on the society and economy there, Huang and others have argued.

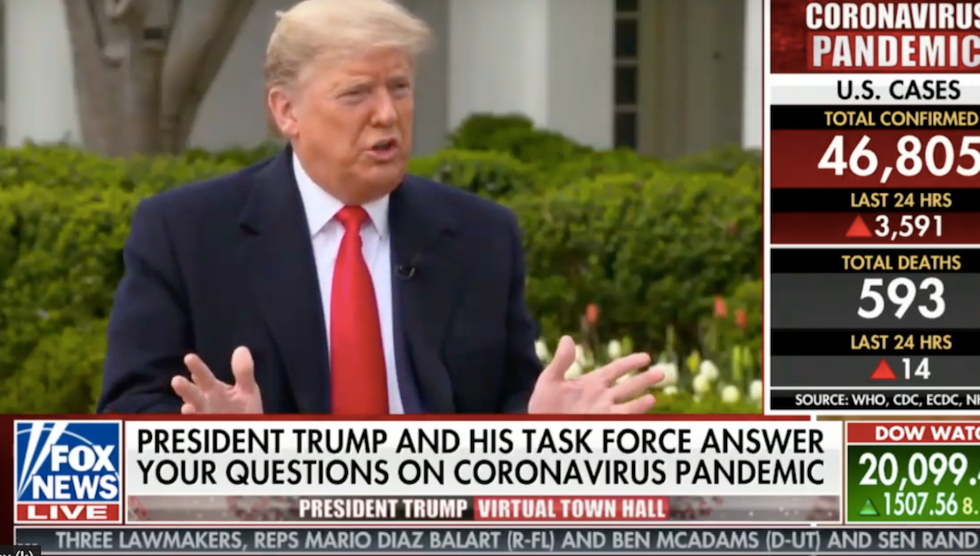

The United States is not China, and President Trump continues to put the economic risks of COVID-19 above its human toll. But as the virus continues to spread—with more than 100,00 confirmed cases and 1,500 deaths—it raises the question: How much further can and should the US government intervene in individual lives in service of the public good? For insight into questions about the tensions between civil liberties and public health, I turned to Wendy K. Mariner, a professor of health law and ethics and human rights at Boston University. In 2017, Mariner co-authored a paper with her colleague Michael R. Ulrich on quarantine and the federal role in epidemics. The professors argue for a “rights-based” approach to controlling epidemics, warning that “unconstrained use of quarantines undermines both the rule of law and public confidence in government decisions in times of crisis.”

I caught up with Mariner, who is delivering the rest of the semester’s lectures remotely from her home, to understand how much authority the government has to contain us—and whether we could ever move toward the autocratic restrictions the Chinese government imposed.

Could President Trump impose a national quarantine, and what would that look like?

He has a lot of authority under many different federal statutes. Most of them are designed to provide funding in an emergency to help with disasters: the National Emergencies Act, and the Stafford Act just got invoked because of his declaration. The Department of Health and Human Services gives authority to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to locate people who are suspected of being infected with one of the diseases described in a presidential executive order. These are the big ones like Ebola, MERS, SARS, and this coronavirus.

We make a distinction between isolation, which usually refers to an individual, and quarantine, which tends to refer to groups—people who aren’t sick but might have a disease so we don’t want them wandering about unknowingly exposing other people.

The individual isolation is pretty straightforward in the sense that it truly is someone who’s sick. Usually it’s in the hospital where they want to be voluntarily, and that’s rarely an issue. [Forced isolation] does happen from time to time at the state level, with someone who, say, may have active contagious tuberculosis and, for one reason or another, can’t seem to take precautions, or doesn’t understand—maybe they have a developmental disability. It’s happened a few times and often with someone who’s homeless, who basically can’t stay away from other people.

At this point, couldn’t most of us be considered quarantine-able?

Well, that’s the concern, right? Who knows? This is really unprecedented. Because coronavirus appears to be transmissible before anyone knows she has it, before there are symptoms, which hasn’t been true so much in the past. This makes the lack of testing and things like that very, very troubling. We won’t know if people aren’t being tested.

We’ve seen some images from China of people locked in their apartment buildings, receiving messages from large speakers set up outside. Could our federal government lock us in our houses? What if we have no symptoms?

I think as a practical matter, no, it’s not going to do that. We don’t have a system quite like China where people are perhaps more willing to do what the government requires, as they did in the province where Wuhan is located. The Chinese government has far more coercive powers. The United States has a population that is, shall we say, somewhat more skeptical of government decisions.

But as I’ve argued elsewhere, we have to make it possible for people to stay home. And fortunately, the country is finally waking up to the notion that people do need to be able to survive both financially as well as physically. We need protections for people who don’t get paid, can’t pay the rent, lose their jobs. Gig workers, freelancers. That’s what makes it possible for people to stay home voluntarily, and it obviates the need for a government order that actually requires people to stay home.

How could a broad quarantine be enforced?

I would make a clear distinction between enforcing an individual order—an order directed to an individual or a family—and an order that would direct an entire population in a city or a state, for example, to stay home. Enforcing a single individual wouldn’t be that difficult. You could station policemen outside the home or check every once in a while to make sure that they’re not violating the orders. During the plague in other countries, notices would be put on the door: “Quarantine, stay away from this house, people inside might be infected, don’t come in.”

As a practical matter, it’s very difficult to enforce a large-scale quarantine geographically. You’re not going to line up an entire police force surrounding a city to make sure nobody goes in or out—that’s just not physically possible. It doesn’t really matter what authority you have, if it doesn’t work.

But what about using the military?

That actually might be counterproductive. And I say that because it could inflame the population who might otherwise be perfectly happy to stay home to say, “Wait a minute, we’ve got the military now coming against the civilian population.”

I think of during SARS in 2003, when the Chinese government announced that they were going to create a quarantine facility in one city and impose a geographic quarantine. Something like 250,000 people fled the city.

If you put into place measures that frighten people and make them feel as though they’re under siege, they could just bail and leave.

You write about how “shelter in place” guidelines have traditionally worked better than coercive quarantines. Do you think that’s going to be the furthest that US authorities, like mayors or governors, will go? What could be the next step?

I hope that’s as far as they have to go. If there is a case here or there of an individual not behaving smartly, the government could respond. At that point, it would probably be at the state level, because this is where most individual instances of involuntary detention occur.

But it would be hard to try and create a full cordon sanitaire that was manned by law enforcement. We don’t have enough law enforcement, and they have other important things to do.

Are there any cases that stand out in the history of the United States that have set a precedent for the government’s authority to quarantine people on a large scale?

Most examples in our history have been designed to apply to individuals on a case-by-case basis, not entire populations. So people are understandably a bit out to sea as to whether any of these laws and examples apply.

The only one that stands out was with the bubonic plague in San Francisco at the turn of the 1900s. It never got to the Supreme Court. But there was an actual quarantine around most of Chinatown in San Francisco. And it was a bit serpentine because it excluded a number of the white, or the non-Chinese, businesses. It was based in theory on the notion that people of Chinese heritage were more susceptible to the plague, which was of course nonsense.

Then a federal court struck it down, because it was a violation of equal protection. It was discriminatory, it was directed only at Chinese, and it was also arbitrary because it essentially confined people who were and were not sick in the same area, thereby encouraging the transmission of the infection, rather than preventing it.

You’ve written about how current guidelines around epidemics risk the government stepping on our constitutional rights.

Ordinarily, in order to deprive someone who has not committed a crime of physical liberty, the government would have to establish, at least with respect to contagious disease, two things: 1) the person is infected with a serious contagious disease, not just the common cold, that is easily transmitted person to person; and 2) that they are not capable of taking precautions to avoid transmitting the infection unless they are confined.

The current regulations issued under the Public Health Service Act under the authority of the HHS and the CDC have sort of ignored the second half of that. And they watered down the first by simply arguing that a person could be detained and isolated, if an official had a reasonable belief that the person was infected, period. That’s a much broader interpretation of their authority than I think the Constitution would ordinarily allow.

Now, I will give you one caveat: With a disease like COVID-19, that can be transmitted before one has symptoms, it might be reasonable to detain someone long enough to test them and see if they are in fact infected, and then see whether they take precautions and stay home and not infect anybody else. And of course, get medical care if they actually develop severe symptoms.

You wrote a paper on the role of the federal government during epidemics before the coronavirus pandemic, so I wondered if this crisis has changed your perspective in any way.

Not really. The reason is because the federal government has ability to provide the resources that are needed in a crisis like this. And I’m glad that many people in the health policy field as well as state, local, and the federal government are finally recognizing that the government should really use its authority to provide those resources, get the funding out, get the stockpiles out, release them to the public—and it should have been done weeks ago. That is going to be far more effective than locking people up.

I think it would be useful to have a more automatic trigger for things like this, like more expansive provisions for sick leave, and sick leave that allows payment for people to stay home voluntarily when they’re not sick. That’s key in this case, right? Because we’re asking people to stay home, who are not sick and don’t have symptoms.

People need to be recognized and compensated for doing the right thing, especially people who need that income and the income that they’re losing to survive financially. I’d like to see laws in place that make these kinds of personal sacrifices feasible for people. We need to have reserves in place if this kind of thing happens again. And it will.

This interview has been condensed and lightly edited.