Nardus Engelbrecht/AP

Just moments before a mass shooter opened fire in a Virginia Beach building last year, killing a dozen co-workers and injuring several others, the order came in: Shelter in place. The words rang loudly in Florida as Hurricane Michael battered the state in 2018: “SHELTER IN PLACE.” Likewise in Los Angeles in 2016 when police blared “shelter in place” after a truck carrying sulfuric acid and toxic gas exploded, sending deadly fumes downtown.

No one needs to be told what “shelter in place” means in the crosshairs of carnage: Shootings, storms, and chemical fire tell you what to do. Take cover until the coast is clear on order of officials. No carve-outs for “essential” ice cream walks. But there’s growing confusion over what “shelter in place” and “stay at home” mean in the path of this pandemic. An open secret: It’s a distinction without much difference if you go by how interchangeably they’re used in the media, but “shelter in place” is the better fit, even if it rattled New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo. The governor raged against “shelter in place” in favor of “stay at home,” presumably because “shelter in place” too readily evokes Cold War flashes of bunkers, duck-and-cover, nuclear fallout. “Words matter” was Cuomo’s press-conference point, perfectly summing up the limited response available to us: We don’t control the threat. We can’t see it. So we’ll take our control and clarity where we can, even at the level of language. Words will save lives.

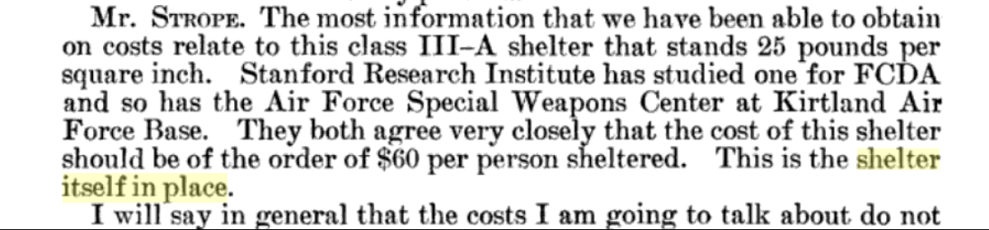

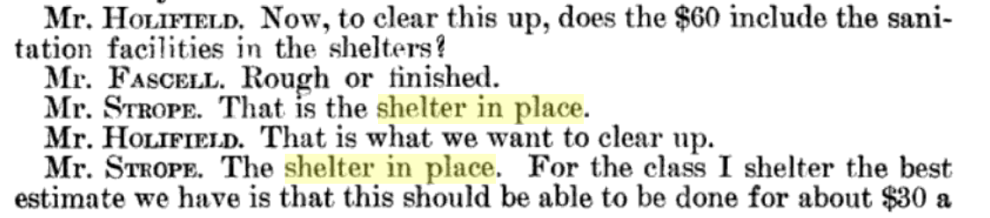

Cuomo wasn’t wrong about the connotations of “shelter in place.” Historian Marian Moser Jones, a public health ethicist at the University of Maryland, points me to the phrase’s first appearance in unclassified federal documents. It was in a transcript of a 1957 House subcommittee hearing about reorganizing the “civil defense functions of the federal government”—a bit of Cold War business. The words were uttered by an expert witness, one Dr. W.E. Strope, on hand to talk about what he called “my first love, which was damage analysis.”

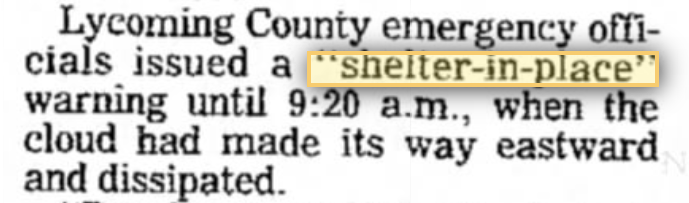

The first newspaper mention I could find was in a 1978 Indiana Gazette article headlined “Chlorine Leak Sends 37 to Hospitals”:

Lycoming County emergency officials issued a “shelter-in-place” warning until 9:20 a.m., when the cloud had made its way eastward and dissipated.

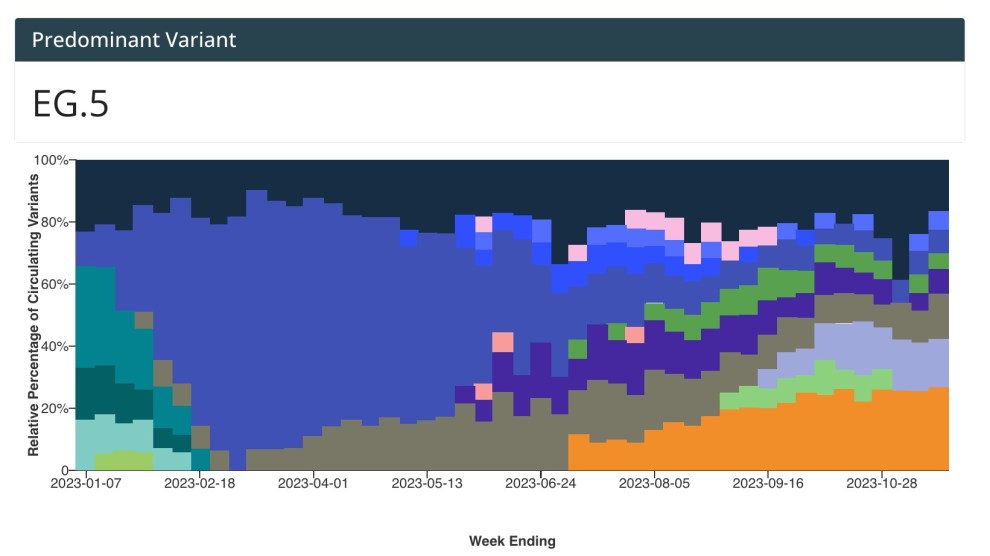

“Shelter in such places” appeared 22 years earlier in the Oakland Tribune—an article on President Eisenhower’s pitch for “shelters in such places as schools” to mitigate looming “thermonuclear explosions”—and variations like it fill the archives. But we don’t get “shelter in place” until the ’70s, in connection with evacuation plans, like Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld’s use in a 1976 “defense posture” report. “Shelter in place” spiked in the ’90s and again post-9/11, when public security infrastructure was centralized under one roof—the Department of Homeland Security. As tornadoes and pandemics came into the department’s fold alongside terror threats, the rhetoric started to merge and militarize accordingly. “So it’s easy to see how a term common in response to a chemical spill such as ‘shelter in place’ has bled over to the response to a pandemic,” Jones says.

To hear Scott Reitz tell it, “shelter in place” is the perfect conjuring phrase for the virus’s deadliness. A 30-year veteran of the LAPD and a 10-year SWAT instructor and operator, Reitz tells me that “shelter in place” gets quickly to the point. “This is a biological active shooter,” he says. Treat it like one. “It’s a lot worse than” a conventional mass shooter.

“In an active-shooter scenario, we can neutralize that. We’ll go in, we search out the source, we engage and put him down and that’s it. But the coronavirus is something where if the front-line doctors don’t have enough medical equipment to ensure their safety, and they go down, it is really critical.”

Reitz stops short: “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet”—or as toxic. Overparsing language doesn’t help, but getting the urgency down does. “It doesn’t really matter the terminology applied” to staying at home or sheltering in place as long as “you stop congregating.”

In hospitals, there’s nothing about “shelter in place” or “quarantine.” The talk is of “isolation,” says Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine and infectious disease at Vanderbilt University and longtime consultant to the Centers for Disease Control. “We don’t ‘quarantine’ anyone in the hospital. We ‘isolate’ them. People in quarantine don’t necessarily have the illness, but they’ve been exposed, whereas people who are ‘isolated’ are suspected of having the disease or we know have the disease.”

“Quarantine” comes from the Italian quaranta giorni, for the “40 days” that ships docking in Venice in the 14th century had to anchor and wait, for fear of spreading disease, according to the CDC. Curiously, the dictionary disagrees, pointing to French, not Italian, but the meaning holds: preventive isolation.

“It gets a little blurry around the edges,” Schaffner says, “but we have to get the message exactly right: ‘Stay at home’ doesn’t have the same ominous understanding that there’s a threat outside,” like “shelter in place” does.

At least “‘shelter in place’ has the potential to galvanize community. It’s a wartime term,” says Dana March Palmer, a professor of epidemiology at Columbia University. “This is a war, against a highly transmissible and deadly pathogen.”

“Historically speaking, ‘shelter in place’ arose as an expression referring to an order to stay exactly where one is when the shelter-in-place order is received,” says Richard Janda, co-editor of The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. “Technically then, someone who hears a shelter-in-place notice while in an outhouse should stay in the outhouse. If an approaching hurricane is visible through the cracks of the outhouse, it would probably be better to stay there than run across the yard to a nearby house. But ‘shelter in place’ overlaps with ‘stay at home’ in a plurality of cases, perhaps even a majority, so it’s not hard to see how and why ‘stay at home’ has come to be the predominant current meaning of ‘shelter in place.'”

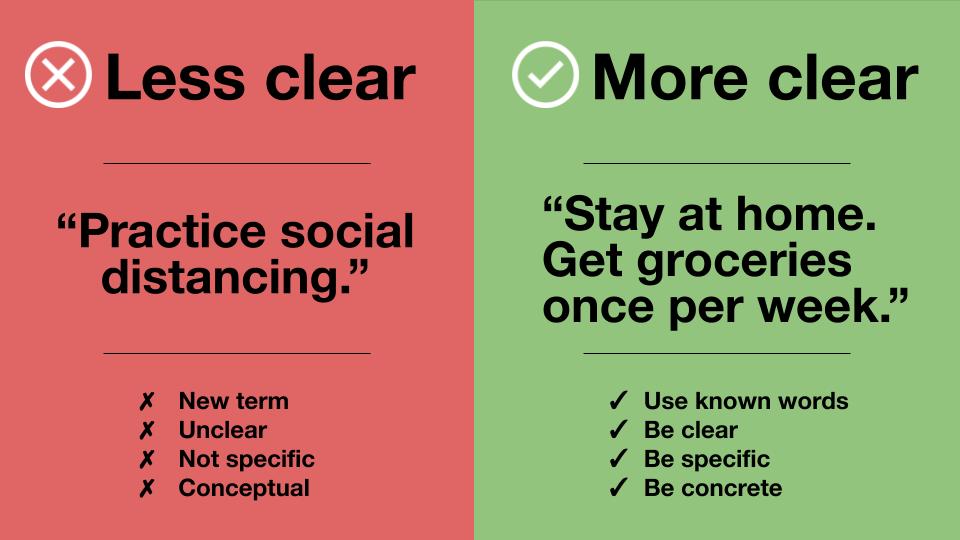

The biggest misnomer: social distancing. Physical distancing is needed, not social distancing. Video chats socially connect us, which is why Reddit wasted no time dunking and dancing on the misuse of “social distancing” in this meme:

But wishing away a misnomer is useless. Everyone knows the underlying meaning. “The explanatory language that follows the short descriptive words” is what saves lives, Schaffner says.

Ask enough experts and a troubling truth emerges: Our national vocabulary hasn’t yet adapted to the virus; we’re still looking for a shared terminology. All we have for now is the aging grammar of an earlier moment of collective anxiety, when Americans feared infiltration and invasion by an “invisible enemy” of another kind. The Cold War lives on, Cuomo be damned.

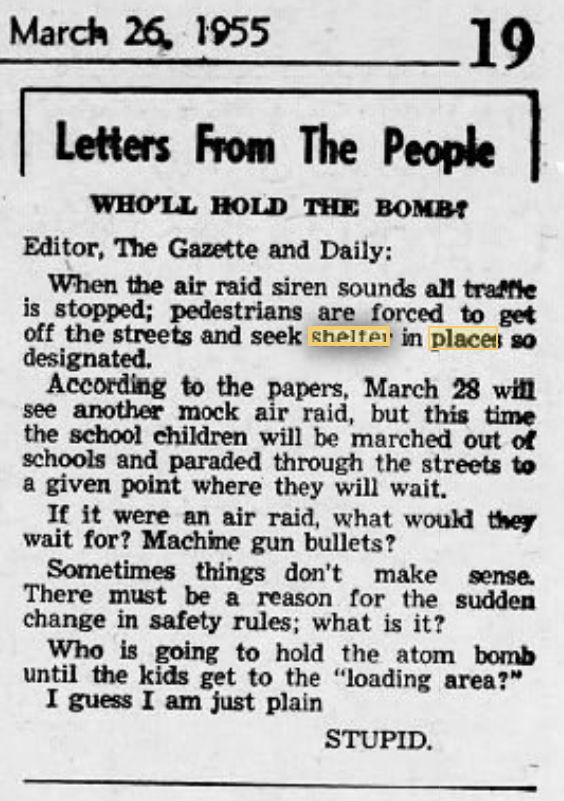

As ever, history haunts us. A postcard from the past, exactly 65 years ago Thursday, in a Pennsylvania newspaper:

March 26, 1955

LETTERS FROM THE PEOPLE

WHO’LL HOLD THE BOMB?

Editor, The Gazette and Daily:

When the air raid siren sounds, all traffic is stopped; pedestrians are forced together off the streets and seek shelter in places so designated….[Tomorrow] will see another mock air raid, but this time the school children will be…paraded through the streets to a given point where they will wait.

If it were an air raid, what would they wait for? Machine gun bullets?

Sometimes things don’t make sense. There must be a reason for the sudden change in safety rules; what is it?

Who is going to hold the atom bomb until the kids get to the “loading area”? I guess I am just plain

STUPID.

Who is going to hold the coronavirus at a crosswalk when the kids go outside? “STUPID” is what the letter writer isn’t. Who wrote that letter? Are you out there, reading this, 65 years later? If you were, say, 25 or 30 at the time, you’d be 90 or 95 now. Are you sheltered?

In 65 more years, let a reader find this, free of pandemic, and ask if we, too, sheltered in place until the coast was clear.