Haven Daley/AP

Update: On May 1, the University of California, San Francisco, confirmed that all 1,845 swab tests conducted in Bolinas tested negative for COVID-19. Antibody tests—which will reveal whether anyone was previously infected—will take several weeks to analyze.

Just after 6 a.m. on Tuesday, Dr. Aenor Sawyer pulled her big red tractor into a dirt lot beside the fire station in Bolinas, California. In the lot were six white tents—”like Cirque du Soleil,” says Sawyer, an orthopedist at the University of California, San Francisco. As the sun climbed over the green hills to the east, she began preparing for the dozens of volunteers who would soon show up to pull off a feat that sounds impossible practically anywhere else in the country right now: Testing everyone in one town, whether they have symptoms or not, for COVID-19 infections and antibodies.

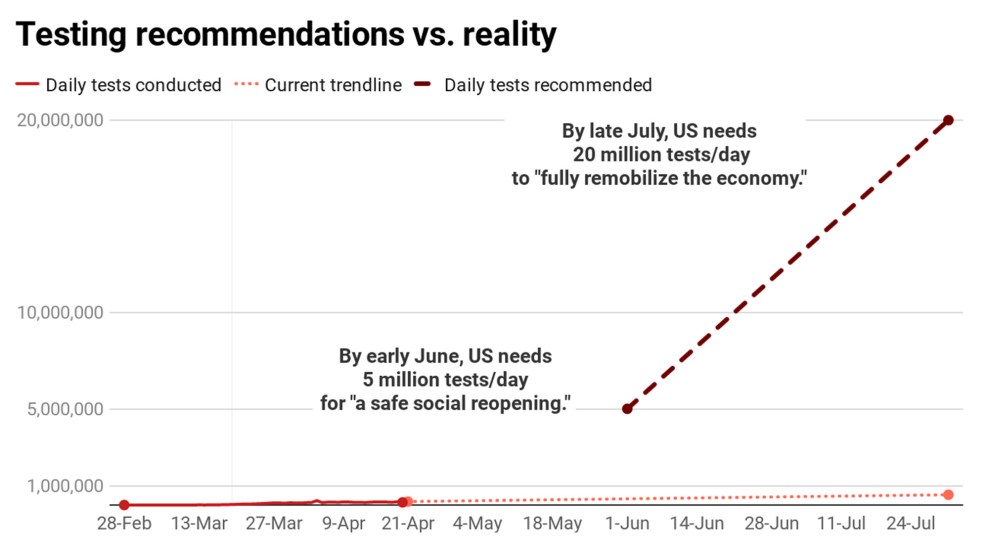

As the president insists widespread testing is already taking place, governors clamor for more tests, and anxious families line up in their cars overnight to wait for nasal swabs, the United States is falling woefully short of the millions of daily tests experts estimate will be needed to safely lift social distancing restrictions. But in Bolinas, an unincorporated seaside community about 30 miles north of San Francisco that’s known as an enclave of aging hippies and a retreat for wealthy weekenders, a handful of homeowners, community volunteers, and UCSF researchers managed to organize enough tests for the town’s residents, essential workers, and first responders. As of Tuesday, nearly 1,800 people had signed up for an appointment to be tested over a four-day period this week.

Researchers are hoping the project will capture rare data showing how COVID-19 may be spreading under the radar. (Bolinas had zero confirmed cases as the testing project kicked off.) The UCSF scientists will compare the results from the town to those from a similar testing effort taking place this weekend in a dense section of San Francisco’s heavily Latinx Mission District.

“Right now we’re in the middle of a pandemic that is highly infectious and has taken many, many, many lives, and we still have no understanding of how it moves and spreads through a community.” Sawyer says. “Part of that is because not everyone gets symptomatic. They don’t all end up at the hospital, and they don’t all become known cases of COVID-19. There are many people out in society that are infected, or have been infected, that are invisible.”

While testing Bolinas may have inherent research value, it would not have happened without the pull of its more affluent residents. The $350,000 project was dreamed up—and, in large part, paid for—by a handful of multimillionaires who live or own homes in town, led by venture capitalist Jyri Engeström and biotech entrepreneur Cyrus Harmon. Both were reportedly inspired by the Italian town of Vò, which brought the virus under control in March by testing every resident twice and isolating those who tested positive. They reached out to UCSF, which had recently scaled up its lab capacity with funding from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. “It’s this question of, well, do you just sit around and wait for the federal government to do something or do you try to take action and help?” Engestrom told the Mercury News. The first $100,000 came from Mark Pincus, founder of the mobile gaming giant Zynga.

But on the ground in Bolinas, smaller donations and “thousands of hours” of volunteerism made the project possible, says Sawyer, who started organizing logistics not long after Engestrom and Harmon reached out to UCSF. The organizers acquired protective suits from local hardware stores, gloves from restaurant suppliers, and masks from “friends who sourced them from China,” according to a blog post by Caterina Fake, the co-founder of Flickr, who is married to Engestrom. They hired phlebotomists and figured out a technique to snap lengthy nasal swabs so they would be small enough to transport. And they recruited leaders from different parts of the famously reclusive community to encourage residents to sign up online. “People do often come here to get off the grid,” Sawyer says. “So the idea of signing up for something, for some people, is just unlikely.”

In the 1970s, Bolinas’ fiercely independent residents, concerned about the ecological impact of allowing the town to grow, took control of the local public utility district and successfully froze new development for 49 years (and counting). For decades, local rebels stole the roadsigns pointing the way to town just as fast as the state’s transportation department could put them up. Now a collection of homemade signs on the edge of town warn away unwanted visitors: “Surfers stay home, save lives,” reads one; “It’s a pandemic, not a vacation,” says another. According to the Point Reyes Light‘s popular sheriff’s calls log, Bolinians have been reporting the continued presence of out-of-town surfers and beachgoers without masks.

“We call ourselves the town that fought to save itself,” Sawyer says. “That spirit has surfaced again. It’s the town that fought to test itself.”

In sight of a skatepark ramp painted “Keep Bolinas sacred,” residents arrived by car, bike, foot, and skateboard for their testing appointments. “We expected someone to come on their horse, but they haven’t yet,” Sawyer told me. As residents approached, they were greeted by volunteers who directed them around the site and handed them surgical masks in case the swabs caused them to cough or sneeze. “They told us to arrive exactly at the right time,” says Sha Sha Higby, a local performance artist, who made sure to keep her hands warm on her way to the lot so she would have good circulation for the blood test. At four different stations underneath the white tents, pairs of phlebotomists in full protective suits swabbed noses and throats for samples to be screened for infection.

The phlebotomists also used finger-prick tests to collect blood, which in the next few weeks will be analyzed for the presence of COVID-19 antibodies. Elsewhere in California, antibody studies in Los Angeles and Santa Clara County have indicated that that a far greater numbers of people have been infected with the coronavirus than previously known due to widespread testing shortages and restrictions. (The studies’ conclusions are controversial, in part due to inaccuracies in some antibody test results.)

Bolinas residents have been told they’ll learn the results of their swab tests within the week. But for people living elsewhere in Marin County, qualifying for a test can be difficult. Under the county public health department’s guidelines, doctors should recommend patients for tests only if they are showing symptoms and have had close contact with a COVID-19 patient, or traveled to a coronavirus hot spot within the last two weeks. Others can get a test if they have “moderate and persistent” respiratory illness and haven’t responded to initial therapy and their doctor can’t come up with an alternative diagnosis. Prior to the Bolinas project, Sawyer says, some first responders working in the town could not get tested despite having symptoms. The data from Bolinas might push the county and other governmental bodies to reconsider their protocols for when testing should be done, she adds.

What’s radical about the Bolinas testing project is that it includes even asymptomatic people like Higby, who has been using her time staying at home since late February to work on an elaborate lacquered costume. CDC guidelines currently prioritize testing for hospitalized patients and symptomatic health care workers, followed by people at higher risk for COVID-19 and first responders who are showing symptoms. Those without a cough, fever, or shortness of breath are considered “non-priority.” Sally Peacock, the retired owner of a stable not far from the testing site, also said she’s been feeling just fine for the last few weeks—aside from, as she puts it, the “two-in-the-morning-when-you-sneeze normal paranoia.” Her test, on Wednesday, took about 15 minutes from check-in to when she drove out of the lot.

Sawyer says the testing project reflects the culture of Bolinas—”the spirit of people contributing for the good of the whole, for the entire population, making the community better, doing what we can to fix problems here.” She notes one local woman who has been pinning free home-sewn masks to a clothesline outside the general store. On a recent night, Peacock delivered a takeout order to a resident whose car wouldn’t start. The Bolinas Community Land Trust set up an emergency fund to help residents afford rent and other necessities. The thrice-weekly Bolinas Hearsay News touts an 8 p.m. “gratitude howl” and free sourdough bread deliveries.

“We’re a little random, as a town,” Peacock says. “Things either get done, or they take forever because it takes everybody a million years to agree on anything. So if we can do it, for sure other towns can do it.”

“I’m proud of everybody. I think it’s good,” she says. “Good to be known for something besides taking our road signs down.”