A Dollar General store in Vallejo, California.Justin Sullivan/Getty

One day in early March, Rebecca told her manager at a Dollar General store in South Carolina that she was starting to feel sick. She had a fever, some difficulty breathing. At the time, Rebecca recalls, everyone working at the store seemed to have a fever or cough.

Could she stay home and get paid somehow? she asked her boss. Her boss, Rebecca recalls, told her to come into work or file for food stamps.

At that point Dollar General had not announced a paid sick leave policy. In fact, the fast-growing chain of bargain retail stores, which likes to brag that 75 percent of the country lives within five miles of one of its franchises, wasn’t offering employees much of anything. No gloves, no masks, no hazard pay, no raise. Without PPE, “we were making our own hand sanitizer at the store,” Rebecca says. Her ersatz blend mixed aloe vera and rubbing alcohol.

Rebecca—whose name has been changed for fear the company might retaliate—had been working at the store since March 2019, making about $10 an hour. Stay home? “I couldn’t afford it,” she tells Mother Jones. She didn’t like the thought of filing for food stamps while she’s out sick, and she said as much to her boss.

“That’s the Dollar General way,” her manager said, laughing. Later that week, Rebecca returned to work.

Around that time, Rebecca and a handful of her colleagues began sharing stories over social media. As the pandemic unfolded, they learned a lot about the Dollar General way. They learned that a company focused on expansion—particularly in small, rural areas where even Walmart can’t gain a foothold—is not going to worry overmuch about the health of its lowest workers. They also learned that asking too many questions about such matters can get you fired—as one whistleblower in Dollar General’s corporate office discovered for himself.

On March 16, Daniel Stone began asking the first of too many questions. A market planning analyst in Dollar General’s corporate office near Nashville, Stone was worried that the company’s response to the coronavirus was lacking. He was in a position to know. His job was to analyze locations for new stores. It put him face-to-face with the realities of working in a Dollar General store. He knew population demographics, median income, traffic. He knew the precarity under which employees live. Dollar General now employs 143,000 plus people across 16,300 stores, which are often placed in lower-income, low-population rural areas. “Areas that have like 500 households,” Stone says, where “they’re pricing out general stores.”

The company’s only public acknowledgment of the coronavirus to that point was to announce a designated shopping hour for seniors. Concerned, Stone emailed Dollar General’s chief people officer, Kathy Reardon, and asked about guaranteed sick leave for those working in the store.

Do you work for Dollar General corporate or in a store? We want to hear your stories (especially if you know anything about the “Blue Zone” model). Email me at jrosenberg@motherjones.com.

Stone got a cheery, even heartening response. “You will be proud to know that our practice during this time has been to pay our employees for any missed/scheduled shifts in [our stores] for up to 14 days when they are quarantined for their own illness or to care for a member of their household who is quarantined,” Reardon wrote, according to an email obtained by Mother Jones. If there was a policy in place at the time of her conversation with her manager, Rebecca didn’t know about it and neither, ostensibly, did her boss.

On March 18, Todd Vasos, CEO of Dollar General, sent a similar message to the public, but with an important difference: He said Dollar General offered paid sick leave for “any employee that is forced to remain at home due to a confirmed case” for their “regularly-scheduled hours.” A confirmed case: Did that mean workers needed a positive COVID-19 test result in order to receive sick pay? What if they couldn’t obtain a test in the first place?

Dollar General did not answer specific questions about the timing of protective measures for this article. But it said in a statement that paid sick leave for employees “impacted by COVID-19” includes those waiting for testing, caring for a family member, or “those who must remain home due to their own diagnosis.” It’s not clear if this is the same policy that Vasos announced on March 18.

Stone was happy that the company was paying out at least some sick leave. But he began wondering about other problems—and he wondered what was actually happening in stores. Were workers being sent masks? Was there going to be a bump for hazard pay? He peppered management with more questions. And he began organizing private social media channels so he could hear stories on the ground. Eventually, more than 300 people joined, he says.

They told stories about lax safety, about Dollar General’s neglect over the years, which now seemed to be coming home to roost, according to Stone. When Dollar General said on March 24 that it was releasing $35 million in bonuses, he learned on Facebook that workers were struggling financially. One reached out to him directly asking for help.

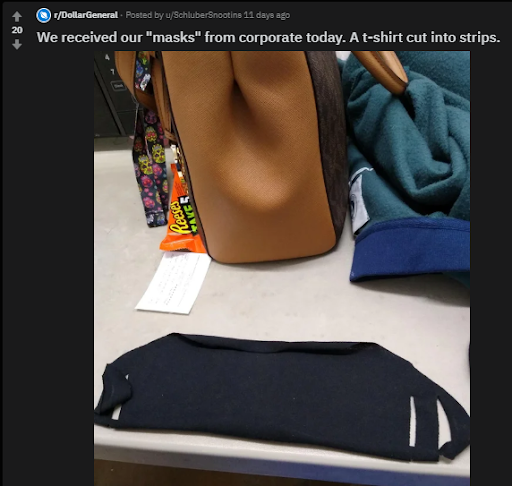

As Dollar General rolled out protective policies, Stone saw more and more problems. There were the masks sent to each store, for instance. “I will never forget this: They were freaking T-shirts,” says Rebecca, who was a member of the Facebook group. “It was like somebody went into a house and cut up a bunch of shirts and said, ‘Here.’” A photo of a mask also showed up on a subreddit devoted to Dollar General.

In a New Jersey store, workers were left to take precautions on their own initiative—closing public restrooms, sanitizing counters, not using customer’s reusable bags, putting up handmade signs about one-way aisles. “DG didn’t suggest we do this,” a worker in that store tells Mother Jones. “It’s a joke.”

Dollar General says it did implement social distancing measures, including plexiglass shields for cashiers, by March 23. The company also closed stores early for more cleaning and distributed PPE. On April 30, Dollar General announced another round of bonuses, adding $25 million to the $35 million already put forward.

The company branded its response to the coronavirus: Its mission, it said, was “Serving Others.” But the workers in Stone’s group could only wonder, What about us? After Dollar General announced it was hiring more workers, Rebecca learned of “mandatory” cuts to overtime hours at her store. A franchise might have a small number of workers—under a dozen, say—but managers were expected to find a way to operate even if people were ill. “Back in February and March, when we were all working with fevers and coughs,” Rebecca says, “we couldn’t close the store because it was a skeleton crew. God forbid we close the store!” By hiring more temporary workers, Dollar General could cut back on hours and overtime pay for full-time staff. “One week I got 18 hours,” Rebecca says. “I get my full-time benefits eating up my whole paycheck.”

For Rebecca and her colleague in New Jersey, there’s nothing new about Dollar General being oblivious to the concerns of the people working in its stores. “They have no idea what goes on at store level,” the New Jersey worker tells Mother Jones. “One December, we were without heat for three weeks—so the COVID-19 response is right up the ‘I don’t give a damn’ alley. It’s all about the dollar.” She says the store doesn’t always feel safe. (A recent NBC News report found at least 27 Dollar General workers were injured in violent robberies from January 2019 to January 2020.) Rebecca recalls a manager having to clean up sewage that flooded her store multiple times over weeks. The manager was unwilling even to talk to higher-ups. “Everybody knows it’s a waste of time to reach out to corporate,” she says. “If you complain you’re headed out the door.”

Stone soon learned that lesson. He continued to ask questions of corporate over email, using the stories he was hearing on social media as examples. Eventually, Dollar General had enough. On April 27, the company fired Stone. “It’s come to management’s attention that there’s been some negative emails and posts and other things like that about the company,” Jason Reese, a senior director of market planning at Dollar General, told Stone on a call, with Leslie Allen, the company’s senior director of human resources, on the line. “There’s been some…sounds like bad blood.”

“I would say that the only bad blood that I have is the current inaction, frankly, towards workers in stores and distribution centers,” Stone replied. “I’m proud to work at this company, and I would like to see it be a leader in the American economy and the zeitgeist and push for higher wages and proper protection.” He referenced the T-shirt masks: “It kind of hurts my heart to see the people on the frontlines subjected to a T-shirt cutout to protect themselves.”

Listen to audio of Daniel Stone getting fired.

Soon after, Stone filed charges with the National Labor Relations Board. And then he posted about the experience on Twitter.

Last week I was let go from my role at @DollarGeneral corporate. This came after months of organizing my fellow coworkers in stores, at corporate, in distribution centers & more.

Please read and share this thread about why myself & others took action to fight for one other.

— Daniel Stone (@DanielGStone) May 5, 2020

In its statement, Dollar General says “we emphatically deny” that Stone was fired for “any unlawful reason,” adding that the company “has a zero-tolerance policy for unlawful retaliation.”

Already 2020 had been for Stone a “what the hell?” kind of year, he says. “Now during a pandemic I’ve been terminated for organizing workers.” He still struggles to understand the logic of it. “What’s negative about asking for better pay?”

Dollar General isn’t known for looking kindly on assertive workers. During its expansion, the company cracked down hard on workers organizing for better conditions. Twice in the past five years, the New Jersey worker tells Mother Jones, corporate reps showed up in the store to hold what she understood to be meetings discouraging unionization. “My cashiers felt bullied,” she says. (One thread in the Dollar General subreddit asked, “Why is dollar general so anti union??” The top reply: “Because then they’d have to treat us like actual human beings.”) You won’t hear employees talk about it much in public, though. Workers told Mother Jones they were afraid to speak on the record specifically because they feared harsh blowback from corporate. They said the employee handbook forbade them from speaking with the press. “People are just scared to lose their job,” Stone says. Dollar General did not respond to questions about these policies.

In December 2017, workers at a Dollar General in Auxvasse, Missouri, voted to unionize in a 4-to-2 vote. It was the first store in the chain to unionize. The company challenged the outcome on the basis of complaints from two workers who had voted yes. One claimed that a fellow employee threatened to slash her tires if she voted against the union; another claimed the same employee offered her $100 to vote yes. In February 2020, the union vote was upheld. But it did not matter.

“They sent us a letter about three weeks ago that they are willing to bargain with us,” says David Cook, president of United Food and Commercial Workers Local 655, which helped the Missouri employees unionize. In the same letter, he says, the company also informed Stone it was closing the store. “So, they are willing to negotiate a contract for us for a store they’re going to close,” Cook tells Mother Jones, chuckling.

He likens it to what Walmart did when meat cutters organized in a handful of stores. The company shut down meat counters across the country. “Dollar General is copying that playbook to the T—we will fight you all the way, we’re trying to get you to quit, we’ll make you miserable,” Cook says. “And we will even close stores before we recognize your union.” Dollar General did not respond to questions about the union drive in Missouri.

Growth is everything at Dollar General. It will not be deterred from its expansionary goals—not by a union, not by an inquisitive market planning analyst, certainly not by a pandemic. In 2017, a writer for Bloomberg Businessweek described a presentation given by Vasos that included a map “that looks similar to an epidemiological forecast, with yellow and green dots spreading like a pox”—the green ones representing “remaining opportunities.” Each store might not sell the mass quantities of a Walmart, but Dollar General sought to make up via sheer ubiquity what it might lack in same-store sales. The company would be everywhere, selling a little. In 2017, Dollar General had 12,483 stores; it now has 16,300. This hit the company’s goal, as Stone described it to Mother Jones: a thousand new locations a year.

“Nothing really impacted our expansion,” Stone says. “It was going to expand regardless of the pandemic.” In fact, the COVID-19 crisis may even give the plans a boost. CNN Business thinks that discount chains like Dollar General “stand to thrive” in a pandemic, as shoppers cut back on their spending and focus on household essentials. On Tuesday, Jackson County, Florida approved a new Dollar General to open.

In the past five years, Dollar General has already taken on 35,000 new employees, giving it nearly 150,000, and some 50,000 additional workers are being added during the pandemic. More stores means more workers laboring under the Dollar General way—more workers getting caught up in what Rebecca calls “the contradictions of their policies and their action.”

“They don’t give a shit what you do. They don’t care what you do,” she says. “They want it done. Cleaned up. Move on.”

Rebecca, in the end, never got tested for the coronavirus. “I still had to come back and work because I didn’t get paid,” she says. “It’s been awful.” She describes the company’s COVID-19 response as a “smack in the face”—not that she expected anything better. By now she knows the Dollar General way.