Lisa Maree Williams/Getty

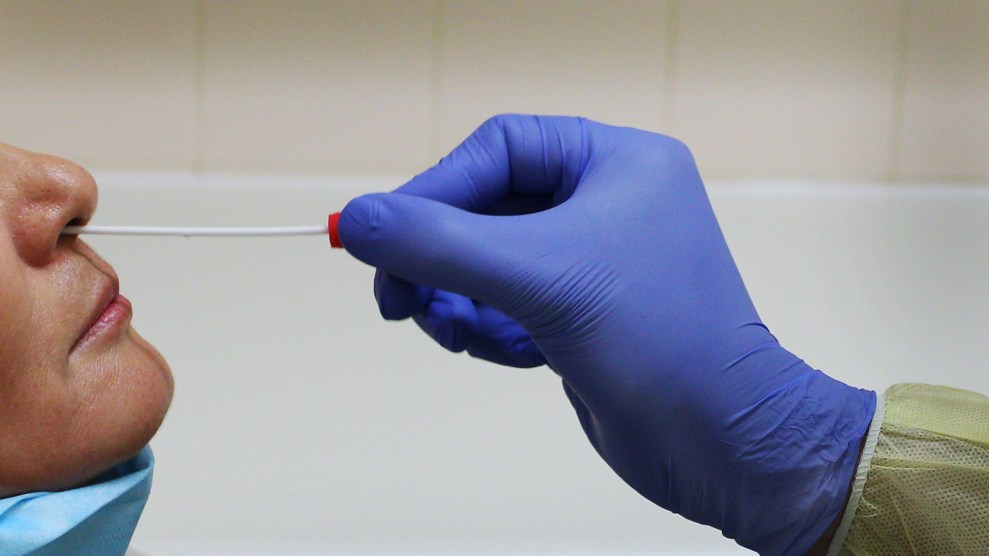

Every day for the last week, between 338,000 and 413,000 people have received coronavirus tests in the United States. For people who aren’t hospitalized, the process typically requires obtaining a doctor’s order, going to a drive-through site, and allowing a medical worker clad in protective gear to stick a long cotton swab deep into the nasal cavity. Yet as the country’s public health agencies struggle to provide and process the millions of daily tests experts say are needed to allow Americans to return to work and school safely, getting tested has to get easier. And that may mean doing it yourself.

At-home testing has promise, says Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. “Theoretically, this approach can reduce the need for clinical providers to collect specimens, increase safety for healthcare providers, and reduce demand for personal protective equipment,” she says. “When you try to do drive-through [testing], you have limited access,” explains Eric Topol, the director and founder of the Scripps Research Translational Institute. “You can only do so many a day. It requires appointments. A lot of vulnerable people can’t get to these drive-throughs. You’re never going to get to the 5 million tests a day or more that we need.”

Nationwide testing proposals by the Rockefeller Foundation and Harvard’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics include a role for at-home tests—either kits that can be mailed to labs or still-in-development tests that deliver an instantaneous result like a home pregnancy test. Of all the options for collecting swabs and samples, at-home test kits have “the lowest demand on personnel and infrastructure and should be a high priority for the FDA,” the Harvard researchers wrote. “There’s no other way we can get to a massive scale of testing outside of a home test kit,” says Topol.

In Seattle, a large-scale study to monitor the regional spread of the coronavirus could offer insight into the efficacy of at-home sample collection. For months, researchers affiliated with local public health authorities have been sending thousands of nasal swabs to healthy and sick people who had to follow instructions for swabbing themselves and then mail the samples to a lab. “The whole idea was if that worked well as a screen for infection, then that would be a great model for the whole country,” Topol says. “But now it’s stopped.” The study, which is funded by Bill Gates, was put on hold last week by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). According to the New York Times, researchers needed additional authorization to let participants know the results of their at-home tests.

Another effort to track the spread of the coronavirus using self-collected saliva and blood is in the works in Massachusetts, according to Michael Mina, an epidemiologist at Harvard. “Instead of having public health people go to apartment buildings, we’re going to be mailing them the supplies and we’ll receive those back and test,” Mina told reporters during a recent press conference. “I think that this is a very good approach and it’s a way to reduce transmission.”

Kits to collect samples at home and mail them to a lab for testing are now available on demand—for a price. In March, a handful of startups began marketing home-collection kits before being quickly shut down by the FDA. But on April 21, the FDA allowed LabCorp, which runs one of the largest networks of commercial labs in the country, to conduct tests on nasal swabs collected at home. LabCorp first offered its home swabbing kits to health care workers and first responders, but now sells the kits for $119 to people who pass a screening by one of its contracted doctors. (LabCorp says it will bill insurers or the federal government directly, meaning there’s no upfront cost to consumers.) Results from the tests will be reported to public health authorities.

And more DIY nasal swabs are coming: Last week, the home health testing company Everlywell, one of the companies that had started marketing kits in March, got a green light from the FDA to sell a home swab kit. Samples collected with the $109 kit could be analyzed with one of a couple authorized tests, giving the company the flexibility to send tests to different labs. The company says its kits will be available by the end of the month.

Yet home testing could run into the same supply-chain issues that have hobbled US testing capacity over the past few months. Like drive-through and hospital-based testing, at-home sample collection relies on specialized nasal swabs, which have been in high demand and surprisingly hard to procure in some places. And there’s some potential for user error. LabCorp warns that incorrectly collected samples may not be tested at all, while false negatives could be more likely if customers don’t ship their samples on the same day they swab themselves.

Meanwhile, emerging research suggests that there may be a better way to test yourself than sticking a swab into the depths of your nasal cavity. Preliminary findings from the Yale School of Public Health suggest that tests that looked for the presence of the coronavirus in saliva were at least as accurate as tests using nasopharyngeal swabs. “With further validation, widespread use of saliva sampling could be transformative for public health efforts,” said Anne Wyllie, a Yale associate research scientist.

On May 8, the FDA allowed Rutgers University to start performing the first tests on home-collected saliva samples. Users spit into a vial, then drop it in the mail. Companies, including the telehealth startups Vault Health and Hims & Hers, promptly cut deals to offer the saliva collection kits for $150 apiece. According to the companies’ websites, buyers are first screened for signs of COVID-19. Hims & Hers requires a consultation with a doctor to approve the test; Vault Health has doctors supervise sample collection over a video call. The samples are tested in the Rutgers lab.

Nuzzo calls at-home saliva collection a “promising development.” But like the home nasal swab kits, they’re still susceptible to supply chain issues, because the lab tests used analyze saliva require chemicals that are in short supply. And both nasal and saliva samples can take several days to get to the lab for analysis, Nuzzo points out. That can make the tests less useful, particularly if people who were negative get infected before receiving their results.

Ideally, we would have a coronavirus test that could be performed at home and immediately return results, “like a pregnancy test,” Topol says. People who tested themselves—perhaps using saliva—would know immediately if they were carrying enough of the virus to transmit it others and could then adjust their behavior accordingly. “We could go into reopening if we could do that,” Topol says. “We could have it at stores, grocery stores and shopping malls and restaurants and workplaces.”

It is already difficult to tally the exact number of coronavirus tests being done across the United States. Home tests that deliver instant results could also be hard to track. It would be difficult to ensure that people report positive results to public health authorities, who need that data to conduct contact tracing and other surveillance efforts to stop potential outbreaks. “Can you have these things have RFID chips in them or something to send out or Bluetooth?” Mina wondered. “I think we’re going to have to figure out how to balance the speed that individuals are getting their results with also ensuring that those results, because this is a public health issue, can get to the public health departments that need to be notified.”

Nuzzo says diagnostic tests that are done entirely at home could be a game-changer for people who need to test themselves frequently, such as those who work in high-risk jobs or live with someone who is medically vulnerable. She points to home HIV tests, which have been sold in stores and online since 2012, as a precedent. “In the past, we’ve always worried about people interpreting their own test results and acting upon information without a healthcare professional in the loop,” she says. “I think maybe as a society we might be shifting away slowly from worry about that, for better or for worse.”

Mina believes such DIY tests are not far off. “These might be a paper strip tests that look like pregnancy tests but actually for the pathogen itself. That might be a two- or five-dollar piece of paper that you can either spit on, or you swab a Q-Tip into your nose and rub it on this thing, or put some solution on it,” he said. The tests wouldn’t even have to be especially sensitive, he explains, so long as they were used daily to check for transmissible levels of the virus. “I think that we might see a moment in the not-too-distant future,” he says, “where that starts to become a reality.”