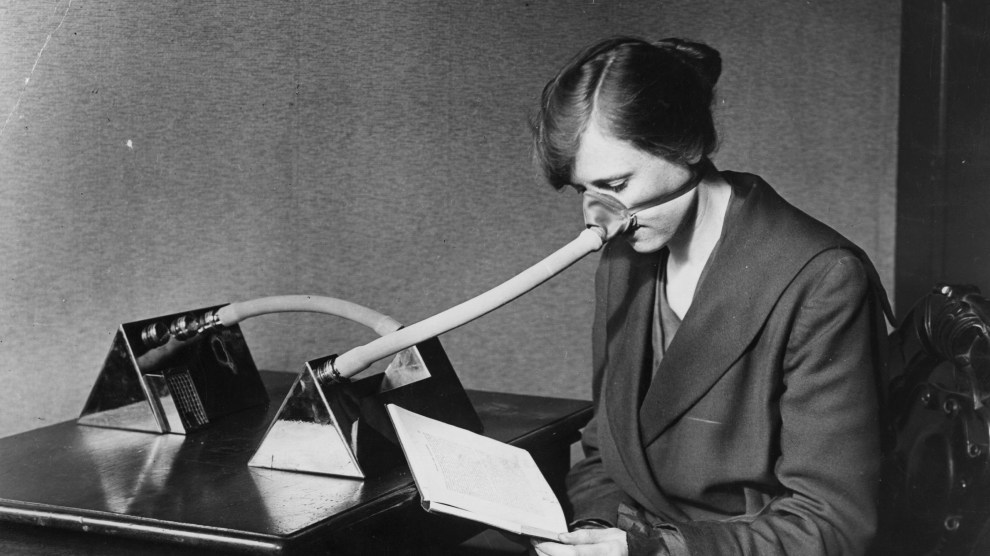

27th February 1919: A woman wearing a flu mask during the flu epidemic. Topical Press Agency/Getty

When my mom was ill with the pancreatic cancer that would take her life, she was frustrated with all the rhetoric describing cancer as a battle. She said that staying alive didn’t feel like an act of bravery. She had no choice. She was just trying to survive.

One of the most painful things about illness, I learned, is that it has a special way of robbing us of our agency. Illnesses attack with a slow, humiliating violence.

That is partly why there are so few books, movies, songs, and poems explicitly about the 1918 flu pandemic, Elizabeth Outka explains in her new book, Viral Modernism: The Influenza Pandemic and Interwar Literature. Despite the fact that the flu claimed 10 times as many American lives as the concurrent world war, it “was hard, first, to characterize a familiar disease like influenza as the enemy,” she writes. “The war provided far more compelling enemies, ones that could be seen and put on posters and placed in stories.” But the lack of obvious references led to a bit of a myth: the lack of flu art.

Outka’s book documents the ways that the 1918 flu pandemic lurks in a lot of modernist literature. It’s just that, like the virus itself, the subject is hidden.

I talked to Outka over Zoom from her home in Richmond, where she teaches a course on 20th- and 21st-century Anglophone literature at the University of Richmond. Here’s a lightly edited transcript of that conversation. You can also catch part of our interview on The Mother Jones Podcast:

Did you ever predict that this would come out during a pandemic?

No. I started working on this book about five years ago. I’m a scholar of modernism—end of 19th century, early 20th century British literature, for the most part—and I’ve done some work in trauma theory. I had never heard of the influenza pandemic. When I started to read about it, I thought, huh, that’s odd. It’s right in my period, 1918-1919. Fifty million to 100 million deaths. Which means the United States lost more lives in the pandemic than we lost in World War I, World War II, Vietnam, Korea, Afghanistan, and Iraq combined. I know enough about trauma to know that you can’t kill off 100 million people and not have it have an impact on the art or the culture.

Then I started to wonder why, in modernist studies, we don’t study this right alongside the war, as two big mass death events of the early 20th century?

We do a lot with World War I, but nothing with the pandemic. It began with that mystery, and then I started to find [the 1918 pandemic] everywhere.

What are some of the examples? Any that people could read now?

If you are interested in pandemic literature, there’s a lot of great things. I think Katherine Anne Porter’s novella Pale Horse, Pale Rider is one of the best pieces of literature we have specifically on the 1918 pandemic. It’s absolutely terrific. William Maxwell’s They Came Like Swallows is a short, beautiful, elegiac novel about the 1918 pandemic. It’s quite sad but it’s really beautiful. I think reading things like W.B. Yeats’ “The Second Coming” or Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway or T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land”—these are difficult texts, but this is a moment where you could see that they do match our mood.

You describe that mood, in part, as “spectral trauma.” You call flu “vast and ubiquitous” but also “diffuse.” So it’s everywhere, but also hidden. I was wondering if you could tell me a bit about these word choices and what air they give to the literature.

For the period itself, it was spectral because the war was what seemed like the real story. People had been fighting the war for four and a half years. They knew the characters. They knew the plot. But the flu lurked as this spectral trauma that made everything worse but didn’t solidify into its own historical event in the way that the war did.

Also, trauma is usually spectral in that it is often something that people remember not directly but diffusely. You can have sensory things in your environment that will trigger it. Right now, we are all being primed for that to happen. I think that you’d be hard pressed to find anybody 10 years from now who won’t see a face mask—or see the tired faces of doctors or nurses, or the beeping of these machines, or a respirator, or the smell of a Clorox wipe—and be brought back to these moments. It becomes like a specter that is everywhere in the brain and in the emotional life.

Part of the difficulty of diseases, especially as contagious infectious disease, is its invisibility. The way that it spreads and the enemy is invisible. You cannot see it.

What could be seen, or felt, that wasn’t invisible by people living and writing in that period?

I think the visuals were probably the most dramatic. This was a very particular kind of flu, and it had very unusual symptoms. It often caused floods or bleeding from the eyes and nose and mouth. So visually that was very dramatic. It also turned people this dark purple color—it’s a heliotrope-cyanosis. That’s something that people write a lot about.

Another [thing] that comes up in the letters everywhere is the sound of the bells. When somebody died, the church bells rang. In communities where they did ring bells for flu deaths there were so many that the bells were ringing all the time.

The body during the flu gave off a fairly distinct odor that was not a good one. People lost their hearing, their hair turned white, their hearts were damaged. It could do damage to the nerves, to the organs, to the brain, the central nervous system. It was a disease that really left lingering traces in the body. And so in terms of bodily sensations, it lived on in people in that way as well.

I love that you included Virginia Woolf’s essay “On Being Ill.” I think anyone who has been sick or has been caring for someone with some kind of deadly illness knows that it’s all-encompassing, but it’s also boring. She speaks to that. You’re trying to track all these minuscule changes in the body, and the stakes are so high, but very little is happening on a day-to-day basis. How did that shape writing about illness?

One of the things that Virginia Woolf says in that essay is that illness doesn’t have a plot. It can be, as you say, the same thing day after day. I think it’s why we like stories that have miracle cures or some sort of resiliency. There’s a lot of literature by survivors who say, Could we stop with the health journey motif? It’s not like that, and it puts too much pressure on people. Most of it is this mundane trying to get by.

I think one of the great things that art does—both when you’re producing art as well as when you’re taking it in—is that it grants a structure that wasn’t there before. Illness can come with a fair degree of unreality, and art can make it into something that has a structure and a shape. I think that grief is also somewhat like that. There’s this terrible vertigo of loss, where you’re kind of scrambling to figure out how to hold onto something, when the very point of loss is that there is nothing to hold onto. Art becomes so much more important.

Another part that I thought was really interesting was this effort to shift the blame onto something material. And so you talk about the rise of spiritualism and of zombies. Thinking specifically about H.P. Lovecraft, you have to kind of wonder if some of this attempt to shift blame contributed to the racism and nationalism and xenophobia that then we saw give rise to World War II. Is that something you’re concerned about today?

I’m very concerned about it. You see this sort of medical language everywhere in Nazi rhetoric. This group is the “disease.” We have to cut it out like a cancer, we have to rid it, we have to purify. It was all about “purification.” All of these disease metaphors used to these monstrous ends.

We see this with Lovecraft. He is just undeniably a racist writer. In many of his stories there’s a lot of racism. There’s a lot of homophobia. He was obsessed with Aryan bloodlines. He felt like immigration was tainting the bloodlines. The other thing that shows up in his writing in interesting ways is this real distrust of doctors and a real distrust of undertakers. While doctors and nurses were hailed for all of the things they were able to do in the pandemic, there was also a kind of undercurrent of anger that you see with Lovecraft. Because there were no treatments, there was nothing that they could do, and doctors inadvertently often spread it. They didn’t mean to, but they went house to house.

So you get this big horrible stew of racism and homophobia and fear of immigrants and anger toward doctors and from some combination of that atmosphere he give us these monsters. They’re proto-zombies. They’re not zombies because Anglophone literature doesn’t have that term until 1929. He has these proto-zombie figures that are corpses that rise up from the dead. They lurch about, they attack people, and they’re cannibalistic—a lot of the things that we associate with zombies. But they are quickly dispatched. Monsters always say a lot about what we fear. I do worry when we have a monster figure and the right thing to do is to kill them all, it can be a dangerous way of thinking about the world. Monsters can be good when they give people a way to see their fears and confront them and defeat them. The problem is when it bleeds over into these much darker things.

Are there any books you’d particularly recommend as many are stuck at home?

It depends on your taste. It might be too much right now to read pandemic literature. We don’t have to saturate ourselves in the trauma we’re experiencing.

After a day of teaching modernism and World War I and the pandemic, when I get home I’m more in the Jurassic Park angle. After 9/11, I found I obsessively read Jane Austen because I needed to know where I was in the story. I wanted an omniscient narrator who was going to tell me what it was, where we were.

If you do want pandemic literature, Emily St. John Mandel has a really fantastic novel, Station Eleven, which is about a fictional flu that takes out 99 percent of the population. It’s so much worse than COVID, and it’s also just an amazing novel. And there is Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, the HBO series or the two plays, which is about the HIV/AIDS crisis. It’s unbelievably powerful.

But do pay attention to whether you need more pandemic literature, or whether you want to use literature for something else. If you need a really good story, listen to that.