The artist Jorge Rodríguez Gerada with a portrait of Dr. Ydelfonso Decoo, an immigrant doctor who died of complications from coronavirus.Pablo Monsalve/Getty

In early March, Dr. Karanjit Sandhu, a hospitalist at the Albert Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia, contracted the coronavirus from a patient. He worried how the virus would affect his body and whether he’d recover. Yet as he spent two weeks in bed with a fever, aches, and extreme fatigue, another concern was hanging over his head: How the illness might affect his family’s immigration status. “If for some reason I couldn’t work and I had to leave my job, we don’t really have a legal status,” he says. “It’s just an unknown, and obviously that created a lot of anxiety on top of being sick.”

“As morbid as it sounds, it’s something we had to eventually think about and prepare for,” says Dr. Bhavna Sharma, who is married to Sandhu and works as a pulmonologist, sleep therapist, and intensive care unit physician at the same hospital. She recalls the two weeks when her husband was battling COVID-19 as one of the most stressful moments of her life. She started preparing for worst-case scenarios in which he became permanently disabled or did not recover at all. If he had died, Sharma says, “Not only do I lose my husband but potentially also lose my job and also have to leave the country within 30 days, move my kids and leave everything behind. So that was definitely a real fear.”

Sandhu, who is from India, has an H-1B, a temporary work visa that’s held by more than 400,000 highly educated workers including doctors, engineers, and researchers. Nearly three-quarters of H-1B visa holders are from India. Sandhu and his family can live in the United States only as long as he is able to work for his employer. (Sharma has an H-4 visa, issued to the spouses and children of H-1B holders.)

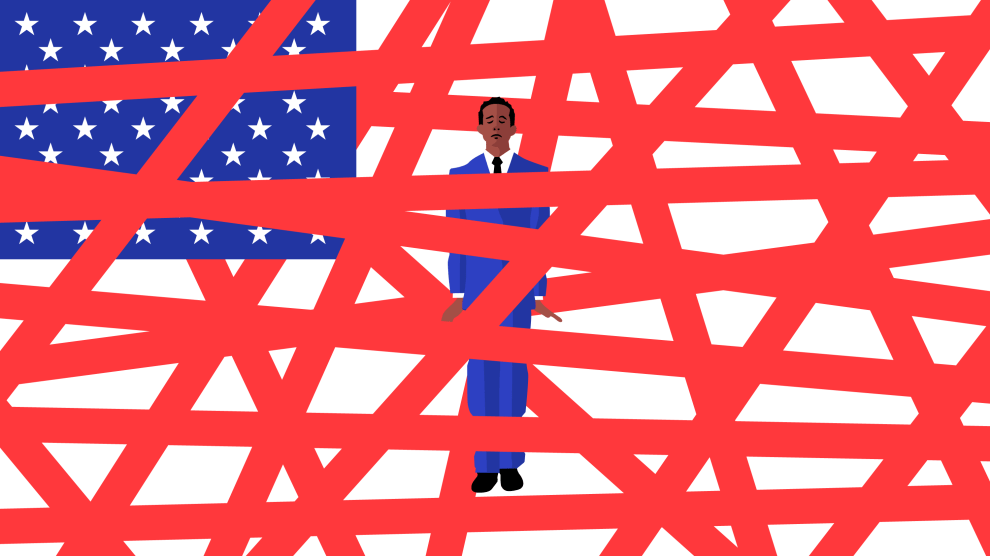

Immigrant doctors such as Sandhu and Sharma are on the frontlines of the coronavirus pandemic, often treating underserved communities that have been hit disproportionately by the disease. At a moment when their work has never been more essential, more of these doctors are speaking out about the rules that leave them and their families without a safety net if they get sick and also make it harder for them to contribute to the fight against COVID-19. With help from advocates and allies in Congress, they are pushing to speed up the sometimes decades-long process of obtaining permanent residency. “You have all of these physicians putting their life on the line. And now they have to wait 20 years to get their green card? There needs to be something to help them out,” says Mahsa Khanbabai, an immigration attorney and the chair of the New England chapter of the American Immigration Lawyers Association.

Credit: Dr. Bhavna Sharma

Dr. Sujit Vakkalanka is a hospitalist in Galax, a town of around 7,000 people in the mountains of southwestern Virginia. Twin County Regional Healthcare, where he works, serves two nearby counties and is the only hospital in a 30-mile radius. If he wants to shop for Indian groceries or watch an Indian movie, he has to travel 100 miles to Charlotte, North Carolina.One in five practicing physicians in the United States is an immigrant. According to a survey conducted by the advocacy group Physicians for American Healthcare Access, nearly half of the physicians serving areas where the per capita income is below $15,000 a year are immigrants.

Vakkalanka’s schedule consists of working for one week and taking one week off. He would like to use his off week to help out at hospitals facing a shortage of doctors. He has a license to practice in New York, and Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s office has contacted him several times asking him to help. But he can’t add a new employer unless without getting a new H-1B, which could take months. “The process is very burdensome and there’s a lot of red tapeism,” Vakkalanka says. “Even if we’re willing to go and help, we’re unable to do it.”

The H-1B visa was created as part of the 1990 Immigration Act to bring skilled workers into the United States. It’s a three-year visa; if an employer sponsors a visa holder worker for permanent residency, they can get unlimited three-year extensions until they get their green card, a prerequisite for obtaining citizenship. Thousands of H-1B holders qualify for green cards every year, yet there’s a cap on how many green cards can be issued to each nationality. As of May 2018, nearly 600,000 H-1B workers and their families were waiting for employment-based green cards. More than 90 percent are Indians, who receive about 10,000 employment-based green cards a year. The green card backlog is daunting: the CATO Institute, a libertarian think tank, estimates the wait time for Indians with advanced degrees is 49 years.

Most people in the line for green cards are tech workers, but there 12,000 physicians on the list, according to estimates from Physicians for American Healthcare Access, which is lobbying for green cards for immigrant doctors, primarily from India.

Frontline doctors on H-1Bs are hopeful about a new bipartisan bill that could streamline their path toward residency. The Healthcare Workforce Resilience Act, introduced by Senators David Perdue (R-Ga.), Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), Todd Young (R-Ind.), Chris Coons (D-Del.), John Cornyn (R-Texas), and Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), would immediately give unused green cards to around 15,000 doctors and 25,000 nurses who are currently in the backlog. “Consider this: one-sixth of our health care workforce is foreign-born,” Durbin said in a press release in late April. “It is unacceptable that thousands of doctors currently working in the U.S. on temporary visas are stuck in the green card backlog, putting their futures in jeopardy and limiting their ability to contribute to the fight against COVID-19.”

Khanbabai, the immigration attorney, notes that many doctors waiting for green cards have dependent kids who could lose their H-4 visas and be deported when they turn 21. That’s what happened to Dr. Preeti Saran, a primary care physician at the Robert Wood Johnson Medical Group, part of Rutgers University in New Jersey. Saran came to the United States in 2002 with her then-12-year-old son. When her son turned 21 he had to go back to India. “How could they not honor someone who has served the country for so long?” asks Saran, who has been waiting for a green card since 2010. “We are not asking for anything other than our status because that can allow us to serve better.” Recently, her son moved back to the United States to pursue graduate studies. But he’s looking for jobs in Canada, and Saran is considering moving there with him.

Like Saran, Sandhu has been stuck in the green card queue for around a decade. He has been working on an H-1B since 2007; his employer sponsored his green card petition in 2010. Most of his colleagues from other countries have already become naturalized citizens. During this time, he and his wife couldn’t pursue fellowships to advance their careers because they can’t change employers easily.

The long wait has started wearing them down. “It’s been the biggest source of anxiety,” he says. “And just the uncertainty, it’s just unrelenting. You have to juggle so many issues just because you’re on a visa, I think, that itself creates chronic anxiety,” he said. It’s “just kind of disappointing that, you know, 10 years down the road, we’re still in the same boat.”

After spending two weeks in isolation after he was infected with COVID-19, Sandhu applied for a National Interest Waiver green card, which is open to physicians who agree to spend five years working in hospitals treating underserved communities. With his seven years of experience working in low-income communities in Philadelphia, he thought he’d qualify. Einstein serves a federally designated “medically underserved area” in North Philadelphia, where nearly a third of the population makes less than $25,000 a year and nearly half the population is Black. As in other cities around the country, COVID-19 is disproportionately affecting Black people in Philadelphia, who account for around 44 percent of the city’s population but 51 percent of its coronavirus fatalities.

If Sandhu was approved, he wouldn’t get a green card immediately, but he would have more flexibility in changing employers or pursuing a new specialty. (He would like to pursue a prestigious fellowship in cardiology within Einstein.) His application to United States Citizenship and Immigration Services required an approval letter from the state of Pennsylvania. But the state’s department of health refused to give its approval, telling him that his past experience at Einstein wouldn’t count toward a National Interest Waiver.

“We have made it our policy not to entertain prior service requests because of the time needed to collect and review five years of documents to ensure compliance with the program, for a physician with whom we had no prior relationship,” said Nate Wardle, spokesperson for the Pennsylvania Department of Health in an email. States have different sets of criteria for which doctors qualify for a National Interest Waiver. Some, including Florida, Georgia, and Illinois, accept doctors’ past experience to count towards the requirement.

The Healthcare Workforce Resilience Act recommends that all states change their National Interest Waiver policies to support the green card application of any physician who has worked for an underserved community for five years. Khanbabai says that considering doctors for permanent residency based on their experience in underserved communities will help states attract doctors, especially since they’re facing a shortage. (Estimates from the Association of American Medical Colleges indicate that the United States could have a shortfall of between 21,000 and 55,000 primary care doctors by 2023.) “Physicians deserve to be acknowledged for their prior work in communities which often have a very difficult time recruiting health care providers,” she says.

There’s no date set for a committee hearing on the bill, but physicians who are part of Physicians for American Healthcare Access are hoping it might pass as a part of the next coronavirus stimulus package. “It’d be a welcome relief if they could pass [the bill],” Sandhu says. “It’d be a godsend. That move would solve a lot of the problems that immigrant physicians are facing. There’re so many of us, who want to contribute to the American society, want to raise their families, live here. I think it’d just be a win-win for everybody.”