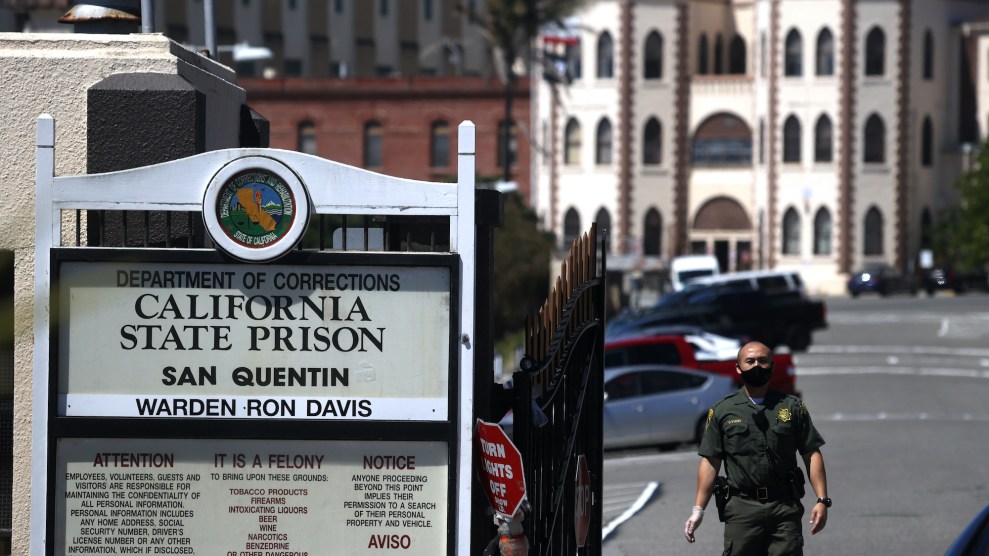

Tents were erected in the San Quentin yard to house prisoners during the COVID-19 outbreakJustin Sullivan/Getty

The California prison that was the site of one of the most severe COVID-19 outbreaks in the United States must cut its population by more than a third, a state appeals court ruled on Tuesday night.

In a scathing opinion, California’s First District Court of Appeals found that the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation has showed “deliberate indifference” to the health of people imprisoned at San Quentin State Prison outside San Francisco. A three-judge panel found that the department violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment when it failed to immediately follow public health experts’ recommendation to halve the prison’s population. The court ordered CDCR officials to reduce the prison’s population to 1,775 people in order to allow for more social distancing inside its grounds. The corrections department could downsize the prison by releasing prisoners or transferring them to other state prisons.

Twenty-eight prisoners died and about three-quarters of the people incarcerated in San Quentin became infected with the coronavirus this summer after untested prisoners from a Southern California prison struggling with its own outbreak were brought in. In early June, after the first handful of prisoners there tested positive, public health experts toured the prison and issued an urgent memo calling for its population to be reduced by half as soon as possible.

“By all accounts, the COVID-19 outbreak at San Quentin has been the worst epidemiological disaster in California correctional history. And there is no assurance San Quentin will not experience a second or even third spike,” Presiding Justice J. Anthony Kline wrote in the opinion. “Failure to immediately adopt and implement measures designed to eliminate double celling, dormitory style housing and other measures to permit physical distancing between inmates is morally indefensible and constitutionally untenable.”

As I reported this summer, San Quentin was particularly vulnerable to an outbreak due to its age, design, and crowding:

In the North and West cell blocks, which hold about 1,600 people—including 300 with four or more COVID-19 risk factors, according to the public health experts—windows are welded shut. Air is recirculated among five tiers of two-person cells, passing freely through grates or bars that open onto narrow walkways. James King, an activist with the Ella Baker Center who was released from San Quentin in December, describes the North and West cell blocks as “concrete boxes” where illness routinely spread in waves. “We used to joke and call it that we were living in a petri dish,” King says.

The lower-security dormitories at San Quentin are also packed, as is a gymnasium filled with rows of bunks that the public health experts said was at a high risk for a “catastrophic super spreader event.” Prisoners in the dorms share toilets, sinks, showers, and phones. (CDCR says that access to phone calls, and showers is staggered to allow for disinfecting between each use.) “I got one person who lives about eight inches away from my face,” says Kerry Rudd, who lives in a San Quentin dorm of about 100 people. “And of course the person on the bunk below me, he lives about four feet from me.”

As of October 14, CDCR had reduced the number of people incarcerated in San Quentin’s to 2,898, in part through a series of release programs announced by Gov. Gavin Newsom in July. In his order, Kline recommended the state further expand its release programs to include prisoners serving time for “a violent crime as defined by law.” That could potentially include some of the roughly 30 percent of San Quentin prisoners serving life sentences.

“Given the length of their minimum sentences, lifers are much older than non-violent offenders at the time they become eligible for parole and receive a release date,” Kline wrote in his order. “Most have by then ‘aged out’ of criminal behavior and present less of a threat to public safety.”

In a statement to Politico, a representative for the state corrections department said it “respectfully disagree[s] with the court’s determination, as CDCR has taken extensive actions to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic” and added that the state currently has its lowest prison population in “decades.” The court’s order takes effect on November 4.