In 2015, I spent four months working undercover as a guard at a medium-security Louisiana prison run by the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) with the aim of reporting on the conditions inside a private prison for Mother Jones. Shortly after I began, I was shown a short promotional video in which two of the company’s founders tell the origin story of their business. In it, T. Don Hutto and Thomas Beasley recount how in 1983 they won “the first contract ever to design, build, finance, and operate a secure correctional facility in the world.” Hutto looks frail, with a shiny white head and oversize glasses, but he speaks with enthusiasm, recalling the story of his company’s first immigration detention contract like he’s giving a blow-by-blow account of a winning high school touchdown. The Immigration and Naturalization Service, the predecessor of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), gave Hutto and Beasley just 90 days to get the job done. From that deal, CCA would grow into a $1.8 billion company that helped build the immigration detention system that President Donald Trump now plans to expand.

Rushed for time, Hutto explains, they convinced the owner of a motel in Houston to lease his property to them, eventually hiring “all his family” as staffers to seal the deal. They surrounded the motel with a 12-foot fence topped with coiled barbed wire. They left up the “Day Rates Available” sign. “We opened the facility on Super Bowl Sunday the end of that January,” Hutto recalls. “So about 10 o’clock that night, we started receiving inmates. I actually took their pictures and fingerprinted them…Several other people walked them to their ‘rooms,’ if you will, and we got our first day’s pay for 87 undocumented aliens.” Both men chuckle.

Today, the company Hutto helped create is the nation’s second-largest private prison operator. (In October 2016, four months after my investigation was published, CCA changed its name to CoreCivic and began describing itself as a “diversified government solutions company.”) Detaining immigrants remains an essential part of its business model: Contracts with ICE make up 25 percent of its revenue. More than two-thirds of all immigration detainees are held by private prison companies such as CoreCivic and the GEO Group, and 9 of the 10 largest immigrant detention centers in the United States are privately operated. The deals can be massive: In 2014 the federal government granted CoreCivic a four-year, $1 billion no-bid contract to run a family detention center in Dilley, Texas. In early summer, it held about 2,000 people. (The facility can hold 2,400 people; CoreCivic gets paid in full even if there are empty beds.)

Bruce Jackson

CoreCivic CEO Damon Hininger told investors in June that “this is probably the most robust kind of sales environment we’ve seen in probably 10 years.” Not long after that, at the height of the crisis sparked by Trump’s decision to separate immigrant children from their families, the company’s stock price jumped 14 percent in less than two weeks. The company does not hold any immigrant children without their families. But it has held mothers whose children have been taken from them, at a facility not far from where Hutto and Beasley opened their impromptu detention center 35 years ago. The facility is named after the man whose story links the renewed fortunes of the for-profit prison industry with the brutal history of America’s prison system: T. Don Hutto.

Listen to author Shane Bauer detail the brutal history of the private prison industry in this episode of the Mother Jones Podcast:

According to CCA lore, Beasley first hit upon the idea of private prisons while making small talk at a Republican presidential fundraiser in the early ’80s. Beasley, who was the chairman of the Tennessee Republican Party, had political connections. His partner, a fellow businessman named Doctor Robert Crants, had experience in real estate. But they needed someone who knew about managing prisons, ideally with a record of doing so at a profit. Hutto, who had just spent five years managing Virginia’s prison system, was the perfect candidate.

RELATED: My Four Months as a Private Prison Guard

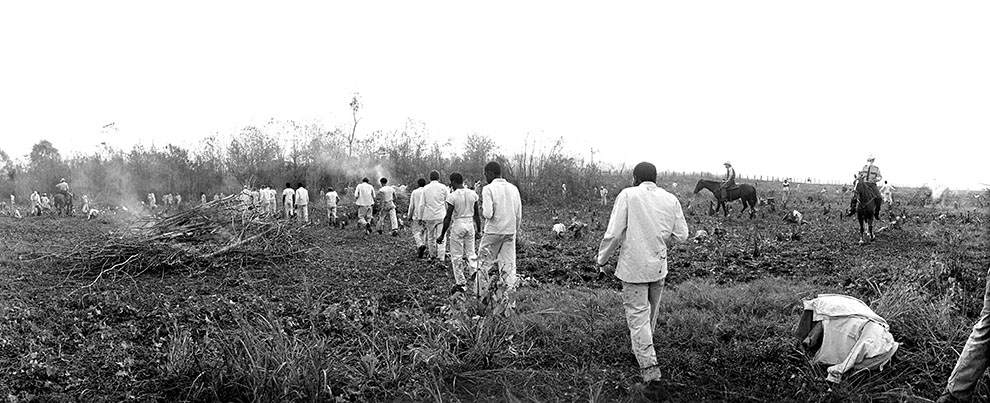

Hutto got his start running prisons in 1967, when he became warden of the Ramsey plantation in Rosharon, Texas. Ramsey was as large as Manhattan and had 1,500 inmates working its cotton fields. Like other prison systems throughout the South, Texas’ had grown directly out of slavery. After the Civil War, cotton and sugar planters found themselves without hands they could force to work. Fortunately for them, the 13th Amendment provided a loophole when it abolished slavery: It said that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude” shall exist in the United States “except as punishment for a crime.” Texas could rent out its prisoners to work at private farms, lumber camps, and coal mines and to help lay railroad tracks. The state eventually became jealous of the easy money that companies and planters were earning from cheap convict labor, so between 1899 and 1918, it bought 13 plantations and turned them into prisons, cutting out the middleman.

Just as slaves had picked cotton more quickly than free farmers, Texas prison labor was undeniably productive. The reason was simple: People work harder when driven by torture. Texas didn’t ban whipping in its prisons until 1941; inmates were primarily flogged for not being productive enough. (Arkansas didn’t ban the lash until 1968.)

Danny Lyon / Magnum Photos

Inmates were routinely put into solitary confinement for “laziness” or not meeting work quotas in the fields. Texas prisons also empowered certain inmates to act as “building tenders,” trusties who managed and punished other prisoners. These convict guards ran the prisons’ living quarters with brutal force; one state investigator found that guards and tenders beat inmates with “fists, axe handles, billy clubs, leaded rubber hose, horse bridles and reins, gun butts, black jacks, and baseball bats.” By using trusties, the state saved money that would otherwise be spent on guards’ wages. A 1974 state report found that these practices continued well into the 1970s. It was in this world that Hutto learned how to run a prison.

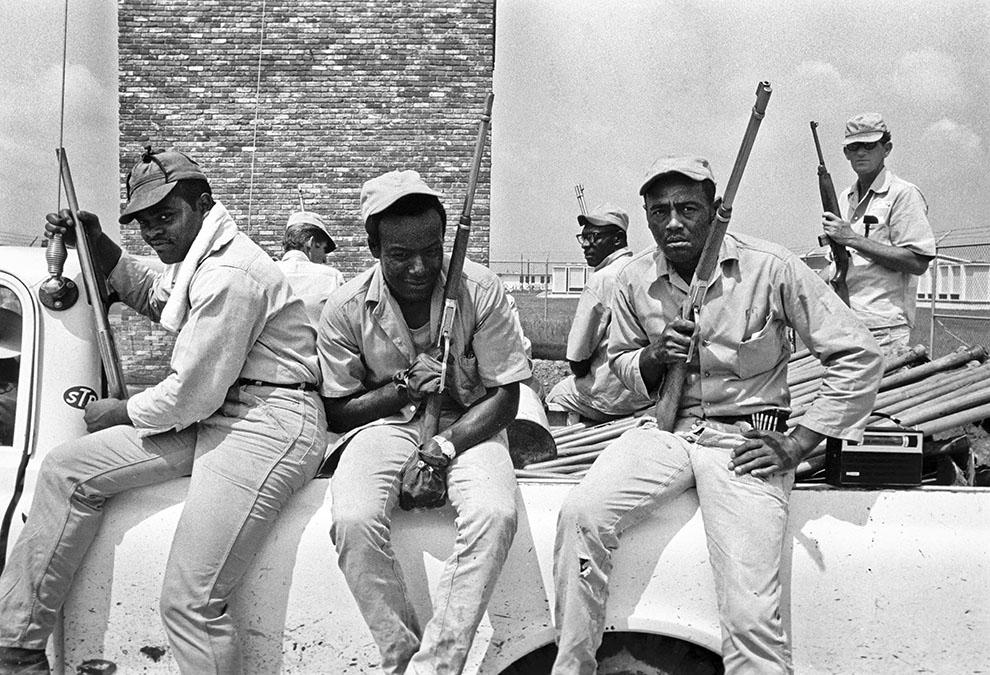

Meanwhile, inmates in neighboring Arkansas sued over horrific conditions at the state’s two prison plantations, where day-to-day operations were also effectively run by trusties armed with whips, revolvers, and shotguns. The job was often done by prisoners convicted of brutal crimes who were willing to assault others. If a trusty shot and killed an inmate said to be escaping, he was granted an immediate parole. In 1965, Arkansas’ prison farms put $250,000 in the state treasury. “To make these profits, the prisoners were driven remorselessly from dawn to dusk in the fields, especially at harvest time,” according to a summary of a state police investigation.

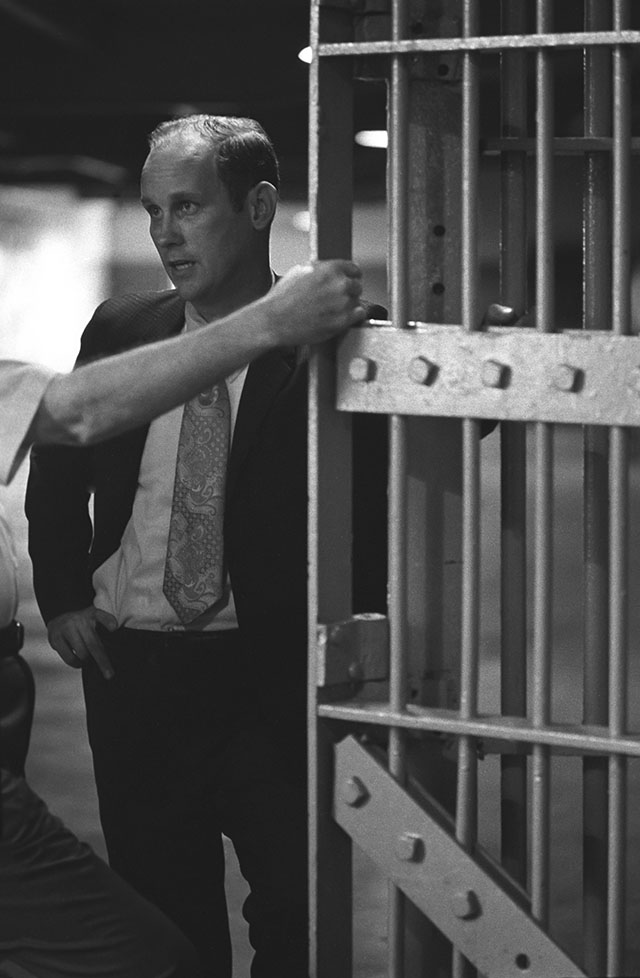

Bruce Jackson

In 1970, a federal court declared the entire Arkansas prison system in violation of the constitutional prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. (The scandal would be fictionalized in the 1980 Robert Redford film, Brubaker.) The prison commissioner needed to be replaced, but there were few people qualified to run Cummins Farm Unit, the 16,000-acre plantation at the heart of the scandal. Arkansas Gov. Dale Bumpers was impressed with the way Hutto managed Ramsey, so in May 1971 he asked Hutto if he’d be interested in running Arkansas’ prison system. Hutto said yes.

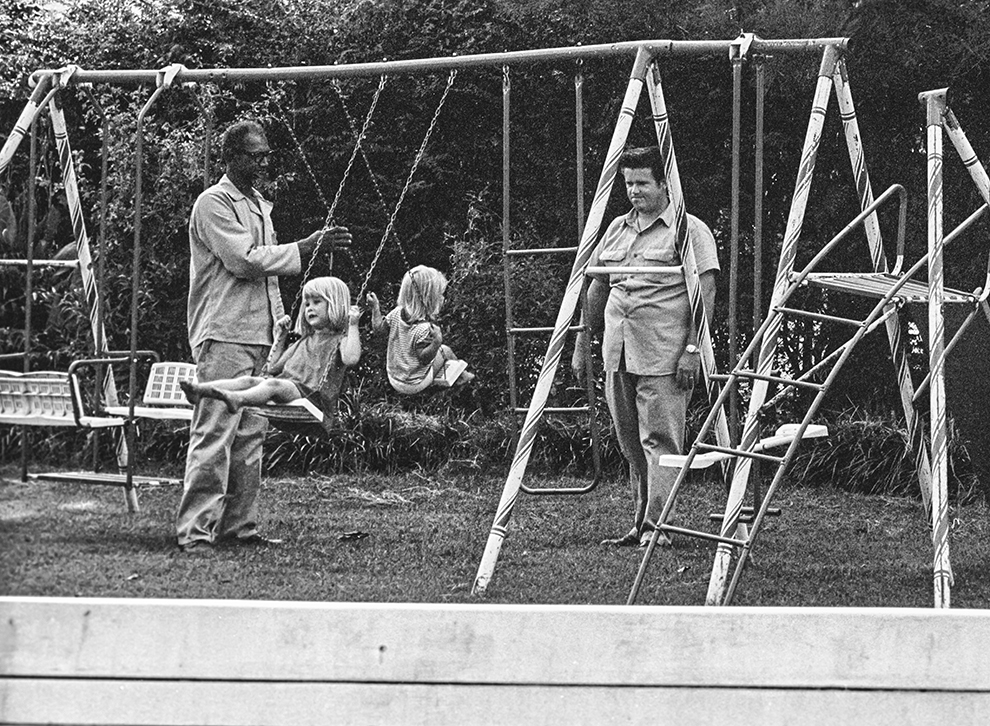

When Hutto went to Arkansas, he chose to live at Cummins, moving his family into the comfortable home where the prison’s superintendent had lived. (One former superintendent had installed a buzzer in his bedroom that rang in the nearby women’s reformatory, where about 40 female inmates lived. He used it when his wife was away, pressing it to summon his favorite female convict.)

After Hutto settled in, Cummins began a prison rodeo. In August 1972, hundreds of people bought tickets to watch inmates compete for small cash prizes. Prisoners wearing cartoonish uniforms with black and white stripes rode broncos. During one inmate’s riding debut, he was kicked in the stomach and had to be carried off on a stretcher. Prisoners piled on top of a greased pig, trying to capture it to win $10. A crowd favorite, according to one article, was an event called “Hard Money,” in which inmates attempted to grab a tobacco pouch containing $75 that was tied between the horns of an enraged bull. Describing the rodeo to a reporter, Hutto said, “Our objective here is to return each inmate to society better equipped to handle his responsibilities, and this can be a start in that direction.”

Bruce Jackson

Hutto’s mandate was to implement the 1970 court ruling that required Arkansas to improve prison conditions, including by reducing the authority of trusties, or convict guards, and hiring “free world” guards instead. When Cummins had lost money after earlier reforms, one state representative complained, “They have refused to make crops. They have refused to let their inmates do what they call ‘stoop labor’ because it’s beneath their dignity.” Hutto also came under pressure to keep the prison farms profitable.

Initially, Hutto demurred, saying it would be very difficult to run an effective prison for monetary gain. “A good prison is very profitable to society,” he said. If a prison could successfully hold a prisoner and reform him enough to prevent him from committing crimes after release, then as far as Hutto was concerned, that prison was operating on a “profitable basis.” Nevertheless, he revamped the farming operation, converting it from a “manual, inefficient, marginal operation to a highly productive mechanized one.” Food crops were swapped with high-volume cash crops like cotton, rice, and soybeans. During Hutto’s first year in Arkansas, farm operations brought in almost $1.7 million in revenue.

Nearly half the high-level positions at Cummins and Arkansas’ other prison farm were filled by Texans who had their own methods of forcing inmates to work. In a federal hearing on prison conditions in Arkansas, inmates testified that failure to pick one’s quota of cotton was grounds for a punishment called “Texas TV.” A prisoner would be forced to stand with his forehead against a wall and his hands behind his back. He would be left there for up to six hours, often without food, sometimes naked. “They get you up in the morning and give you two pieces of bread with syrup and tell you to pick cotton all day and when you don’t pick enough they stick you on that wall so you don’t get any supper or clean clothes,” one inmate testified. “Then the next morning, it’s the same thing. How are you gonna have a good attitude when it doesn’t do no good?”

Another inmate testified that he had been beaten with blackjacks, stripped, and left naked in an unlit “quiet cell” for 28 days for refusing to labor in the fields. Guards blasted air conditioning into his cell without giving him a blanket and fed him only bread, water, and a pastelike “grue,” causing him to lose 30 pounds.

Other prisoners testified they’d been punished by being cuffed behind their backs, put on the hood of a truck, and driven at high speeds through the plantation, sometimes causing them to fall off. Despite the hearing’s findings, Gov. Bumpers said he was satisfied with Hutto, telling reporters it appeared inmates worked harder for him than they did for his predecessor.

Hutto’s prisons attracted more attention when a 17-year-old named Willie Stewart died after visiting Cummins. He had been there as part of a “one-day wonder” program, in which juvenile offenders were given a taste of prison life. Guards would shoot at the teens’ feet as they entered the prison, chase them with cars, or order them to keep up with the fastest cotton pickers. After going through this treatment, Stewart died, prompting an FBI investigation.

In October 1974, a federal appeals court ruled that Arkansas was still failing to “provide a constitutional and, in some respects, even a humane environment” in its prisons. The judge called conditions under Hutto “sub-human” and condemned the use of “various forms of torture and inhumane punishment,” overcrowding, racial discrimination, abuse of solitary confinement, lack of rehabilitative programs and medical care, and continuing use of armed trusties. After the ruling, about 200 inmates refused to work until guards in riot gear forced them into the fields.

Arkansas’ prison system had a terrible reputation, but in another sense, it was thriving. In 1974, prison farming operations made nearly $700,000 in profit. After Hutto left, the farms would operate at a loss. So would other prison plantations across the South. Angola in Louisiana, Parchman in Mississippi, and Ramsey in Texas are still run as prison farms, but today they don’t make money. Not until Hutto introduced a new business model with CCA would prisons be profitable again.

When America’s prison population exploded during the ’80s and ’90s, CCA was perfectly positioned to serve lawmakers who wanted to look tough on crime while minimizing the costs of building and staffing new prisons. But the company hit hard times in the late ’90s; at one point its stock dropped to 18 cents a share. It was saved by the return of immigration detention.

Bruce Jackson

In 2003, the Bush administration launched ICE as part of the newly created Department of Homeland Security. Armed with a $1 billion budget and driven by a new “zero tolerance”-style policy, the agency prepared to triple its beds for immigrant detainees. Over the next 15 years, the immigrant detainee population would jump 91 percent. In May 2006, CCA converted a medium-security prison in Taylor, Texas, into an immigration detention center named after the company’s co-founder. As DHS head Michael Chertoff proclaimed the end of the “catch and release” policies Trump would later rail against, the T. Don Hutto Residential Center became the nation’s largest family immigration detention center, holding more than 500 adults and children awaiting asylum hearings or immigration court decisions. While most families were supposed to spend a few weeks at Hutto, some were held for more than 175 days.

In early 2007, the American Civil Liberties Union sued on behalf of several children held at Hutto, accusing DHS of violating the 1997 Flores settlement, which had set guidelines for the humane treatment of children in immigration detention. According to the suit, children were made to wear “prison garb” and dirty underwear and were kept in small cells for 12 hours a day with an hour of recreation. They could not have toys and did not have privacy while getting dressed or using the bathroom. One child at Hutto wrote, “I don’t like to stay in this jail. I’m only nine years old…This place is not good for me.” Another declared in block letters, “Help!! I hate this place.”

A federal judge called out Hutto for its “questionable” living conditions, including the poor food, inadequate medical care, and prisonlike environment. He also expressed alarm that guards had threatened to separate young children from their parents for minor infractions, “a disciplinary tactic that is certainly inappropriate and which may well constitute mental abuse.” ICE agreed to improve conditions at the facility, including by allowing children to wear regular clothes and move about freely. In 2009, ICE announced it would no longer hold families at Hutto. (CoreCivic says it ensures “a high standard of care” in its immigration detention facilities. It also says it ran Hutto “in accordance with ICE’s requirements at the time.”) The facility recently detained about 500 women, including dozens whose children were taken away under Trump’s family separation policy. In June, Grassroots Leadership, an anti-private-prison advocacy group, published letters from mothers held at Hutto who expressed anguish over being locked away without their kids. One said staff members at another detention site “told us they were going to adopt our children out to other people.” Regarding life at Hutto, another woman wrote, “They also treat us very badly. [I]f we ask something they answer us so angrily. They’re humiliating us and I feel very bad. I ask God to give me strength for my son. I no longer eat or sleep. I don’t know what to do.”

Even before the outrage over family separation, serious allegations about Hutto had been accumulating. In February, a woman sued CoreCivic, alleging that guards at Hutto had forced her and other detainees to work for $1 or $2 a day; if they refused, they were subject to punishments including solitary confinement. Following complaints that guards had sexually abused detainees and retaliated against a woman who spoke out, 46 members of Congress called for Hutto to be audited to ensure its compliance with the Prison Rape Elimination Act. In late June, commissioners in Williamson County, Texas, decided they’d had enough: They voted to end their county’s contracts with CoreCivic and ICE to operate T. Don Hutto Residential Center.

In May 2017, I visited CoreCivic’s corporate headquarters in Nashville, Tennessee. It had been more than two years since I left my prison job in Louisiana. Shortly after my story ran in Mother Jones, the Obama administration’s Justice Department announced it would stop contracting with private prisons; two weeks later, the Department of Homeland Security signaled it would reconsider its use of private immigration detention. On the eve of the 2016 election, CoreCivic’s stock price plummeted to $14, down from more than $30 earlier in the year.

Bruce Jackson

When I drove up to the parking lot, a pair of security guards in wraparound shades stopped me. I told them I was a shareholder, there to attend the annual shareholders’ meeting, and handed them my ticket. During my reporting, CoreCivic had refused to make any of its executives available to me. So I’d purchased a single share of company stock, which allowed me to go there and see them in person.

After I pulled into the lot, a car driven by a thin, elderly man entered. It was Hutto. He had agreed to an earlier request for an in-person interview, only to suddenly balk. When he got out, I approached him.

“Do you know who I am?” I asked. He said yes but then looked confused. “I’d still like to get a chance to talk to you about founding CCA,” I said.

“Oh, I don’t think I can remember much from those days,” Hutto said before disappearing into the building. “Well, it’s nice to meet you!”

Inside the room where company officials gathered, spirits were high. Trump’s election six months earlier had changed everything: CoreCivic’s stock had jumped 43 percent the day after the vote, more than that of any other publicly traded company. Investors were no doubt buoyed by Trump’s promises to crack down on immigrants and expand private prisons. CoreCivic had given $250,000 to Trump’s inaugural committee. In early 2017, the Justice Department had reversed Barack Obama’s decision to phase out private federal prisons, and Trump had told DHS to get ready to hold tens of thousands more immigrant detainees. Immigration detention had pulled CoreCivic out of a slump once before; it was poised to do so again.

Hutto sat in the front row. When people entered, they went directly to him, shaking his hand reverently.

“Sir, good to see you,” one man said.

“Still alive!” Hutto replied.

Adapted from American Prison: A Reporter’s Undercover Journey Into the Business of Punishment, by Shane Bauer. Published by arrangement with Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2018 by Shane Bauer.