On the morning of his 47th birthday, his first outside prison in three decades, Antonio Espree wakes up around 5 a.m. It’s a cool February day in Phoenix, still dark outside, and his cousin Marlon Bailey is asleep on a bed about an arm’s reach away. Their bedroom has little space for anything but their mattresses, so Espree slips quietly out and heads up to the roof to watch the sunrise.

In the kitchen later, after he pours himself a bowl of cereal, his phone rings. Someone who volunteers at a nearby women’s prison wants advice on how to support an inmate named Tasha Finley, who is about to be released after spending more than two decades in prison for a murder she committed as a teen. Soon she’ll live in a halfway house. “She’s like a baby all over again,” Espree tells the caller. “You have to be there to make sure she understands, and if she don’t understand, you kinda guide her. It’s real; there’s still shit I don’t know.”

Antonio Espree hugs Tasha Finley, who is newly released after spending more than two decades in prison for a murder she committed as a teen, outside the halfway house where she lives.

Barbara Davidson

When Espree was 16, he fatally shot an innocent bystander during a drug turf war near Detroit. The state sent him to die in prison. But in April 2017, he was paroled thanks to a series of Supreme Court decisions arguing that because their brains were not fully developed at the time of their crimes, kids should face more lenient sentences than adult perpetrators. The rulings, which took place between 2010 and 2016, have banned mandatory life-without-parole sentences for teenagers, giving thousands of juvenile lifers around the country a shot at release.

At the time of the rulings, more than 70 percent of juvenile lifers were people of color, and 60 percent were African American. Many had been locked up during the “superpredator” scare of the 1990s, when fearmongering about crime and race led to mandatory sentencing schemes and prosecutors sought to depict teen criminals as adults. The Supreme Court decisions were a chance for states to offer a reprieve to inmates who never thought they’d get one.

After Espree was released, he moved to Phoenix and enrolled in college. He’s one of the lucky ones. Of the roughly 2,800 juvenile lifers serving time in 2016, only about 400 have been freed. Because while the Supreme Court rulings offered hope, they also gave states flexibility to decide how to handle lifers’ pleas for parole. In some states, resentencing has moved slowly, and prosecutors have argued juvenile lifers deserve to stay in prison for good. Which means that today, in Michigan and elsewhere, many are stuck in limbo, wondering if they’ll ever get out.

So Espree feels pressure to prove that people like him can make the most of a second chance. “If she’s the example, she has to succeed,” he says to me, referring to Finley, after he hangs up the phone. “Don’t let her fail.”

Espree’s cousin Bailey, a 49-year-old gender studies professor at Arizona State University, comes out of the bedroom and heats up some coffee on his way to work. The two grew up together in Detroit, and Bailey took him in when he was paroled. They are still getting used to living together in a space meant for one. “See you later,” Bailey tells Espree. “Got your books and all that? Your notes?” Espree asks as his cousin disappears out the door.

The cousins grew up on the west side of Detroit. Espree lived with his two half-brothers, mom, and stepdad, who worked at a glass plant for Ford Motor Co. In the winters, he and his friends would play in the snow; during summers it was tackle football, or they’d build go-karts out of wood and race them down the streets. “He always seemed happy,” says Bailey, “though there was a lot of trauma he was dealing with.” For a while, Bailey’s mom wanted to adopt Espree because of the abuse he faced at home—it wasn’t unusual to find his stepdad snorting cocaine, once off an LP cover, or beating the boys or Espree’s mom. Sometimes Espree would show up in the middle of the night at Bailey’s house in his pajamas, looking for a place to sleep. He struggled to pay attention in school and failed the seventh grade three times.

The adoption never happened, but when his mom turned to drugs and kicked Espree out of the house, he stayed with Bailey’s family temporarily. Bailey, who later came out as gay, says Espree was the only family member who didn’t seem to judge him. “That’s part of the reason he always felt like a brother to me,” Bailey says.

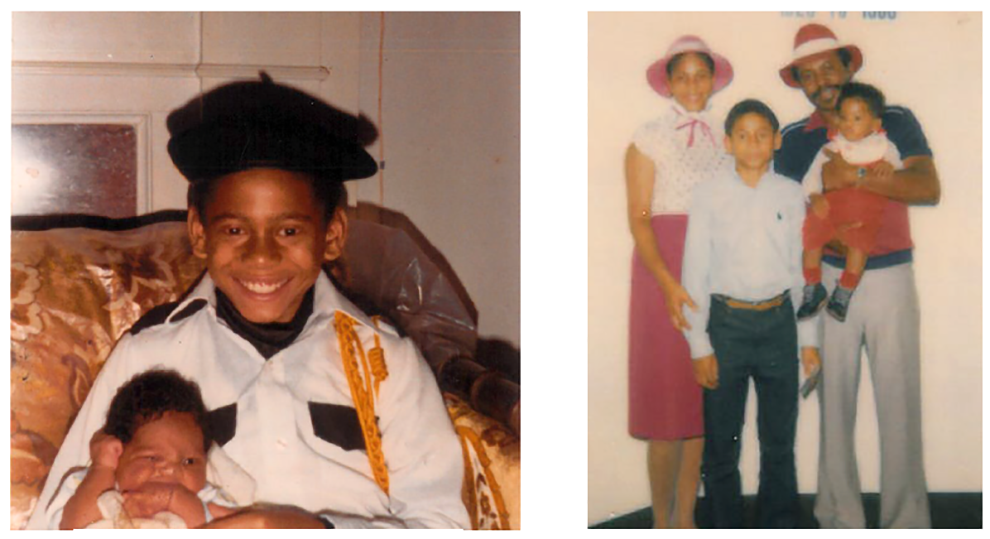

Left: Espree in his Northwest Drill Team uniform, 1982; Right: Espree with his family, 1983.

Courtesy Antonio Espree

One Tuesday night in 1987, a couple of days before New Year’s Eve, Espree, then a 16-year-old high school dropout, was hanging out with some older friends from a gang called Pony Down. The gang was based in Detroit, but they had gone to Ypsilanti to sell cocaine. Their presence angered a local dealer, who had threatened to shoot their leader. The turf war escalated quickly—one of Espree’s friends brought an Uzi submachine gun. Bullets started flying, and one of Espree’s hit 23-year-old Emanuel Billups, who had been standing by the drug dealer. Detectives later visited Espree in the hospital, where he had been brought in critical condition with his own gunshot wounds. Nurses wouldn’t let the detectives talk to their patient, a minor, without his parents there, so Espree says he didn’t find out that his bullet killed a man until a later court hearing. He was tried as an adult and convicted of first-degree murder.

When he went to prison in 1988, Espree was only reading at a middle school level. Years later, he tutored himself with history and law books. When the Supreme Court began ruling on juvenile sentencing in the mid-2000s, he studied transcripts of the arguments.

The first big decision came in 2005, when the justices outlawed the death penalty for teen offenders, making the United States one of the last countries in the world to do so. The ruling drew from a flurry of new research into brain development showing that teens are more impulsive than adults and more influenced by peer pressure.

Five years later, the Supreme Court decided that life-without-parole sentences for teenagers who committed nonhomicide crimes violated the constitutional prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. In 2012, the justices took the next leap: Even if a teen was convicted of homicide, they ruled in Miller v. Alabama, a judge had to consider factors such as the kid’s maturity level and home environment when handing down a punishment. Mandatory life-without-parole sentences, like the one Espree had received, were unconstitutional.

It took another four years for the justices to retroactively apply that decision to people who had already been sentenced. The case revolved around Henry Montgomery, a black man from Louisiana who was 17 when he killed a white sheriff’s deputy in 1963. Racial tensions were so high during the trial that his death sentence was overturned in 1969 and replaced with mandatory life without parole, which his lawyers now argued was unconstitutional. The justices agreed. “Prisoners like Montgomery must be given the opportunity to show their crime did not reflect irreparable corruption,” Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote for the majority. “If it did not, their hope for some years of life outside prison walls must be restored.” He told states to review the prison terms of incarcerated lifers, noting that sentences without parole should be reserved for only the “rarest of juvenile offenders, those whose crimes reflect permanent incorrigibility.”

As a result of these decisions, the number of states banning life without parole for children in all cases, not just in mandatory sentencing schemes, has more than quadrupled to 21 since 2012. Of the 2,800 or so juvenile lifers in 2016, about 1,700 have been resentenced.

But although Justice Kennedy stated that all but the “rarest of juvenile offenders” should get a shot at parole, some prosecutors continue to argue that many do not deserve this benefit, or that they should serve years longer in prison before they can get out. So far, only about 1 in 7 of the juvenile lifers locked up in 2016 have been freed.

There’s dramatic inconsistency in how states have treated their cases. In Pennsylvania, home to one of the nation’s biggest juvenile lifer populations, prosecutors are required to “prove beyond a reasonable doubt” that a defendant can never be rehabilitated if they want to deny the option of parole during resentencing; otherwise, the presumption is he should be given a second chance. So far, the state has released more than 150 juvenile lifers, many under the jurisdiction of Philadelphia’s District Attorney Larry Krasner, who campaigned last year on a platform of reducing mass incarceration.

Cousins Antonio Espree and Marlon Bailey grew up on the west side of Detroit. Bailey says Espree was the only family member who didn’t seem to judge him: “That’s part of the reason he always felt like a brother to me.”

Barbara Davidson

But in Michigan, where 363 juvenile lifers were serving mandatory sentences in 2016, there is no such requirement, and prosecutors have argued that nearly two-thirds of juvenile lifers are those rarest offenders who should be kept in prison for good. “Justice in this country is largely based on where you live,” says Jody Kent Lavy, director of the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, an advocacy group.

Even Henry Montgomery, the plaintiff in the landmark Supreme Court case, isn’t free. In February, the Louisiana parole board rejected his request for release, arguing that he had not finished enough classes in prison. His lawyers countered that he hadn’t been given much of a chance: For his first three decades at Louisiana’s notorious Angola prison, lifers like him were prohibited from taking classes. (About a third of juvenile lifers nationally say they have been denied access to prison educational programs.) When the courses opened up, he was deemed ineligible to complete his GED. A judge described him as a model inmate, but family members of the sheriff’s deputy he killed testified against him at the parole hearing. So Montgomery, now 72 years old, was denied. He’ll have to wait a year to reapply.

During his early years at the Michigan Reformatory, Espree racked up a series of infractions and went to solitary confinement three times before he turned 21. “I was just wild,” he remembers. And he worked hard to develop a reputation for being tough. “Prison was made up of predator and prey,” he says. “When you young and you fear, you give in to that.” Richard Stapleton, who oversaw the prisoner disciplinary process for the Michigan Department of Corrections until 2011, says that kind of misconduct isn’t unusual. “Younger inmates are more likely to commit disciplinary infractions while in prison as a result of their general feelings of hopelessness and not having the opportunity to mature in a normal environment,” he wrote later in an affidavit supporting Espree’s resentencing.

It’s not just about their age. James Garbarino, a psychologist and expert witness in murder trials who focuses on adolescent development, notes in his book Miller’s Children that many juvenile lifers come from rough backgrounds—79 percent saw violence at home and half were physically abused, according to a survey by the Sentencing Project. Chronic trauma during childhood, Garbarino writes, can lead to changes in the brain, including an overdeveloped amygdala, which processes fear, and an underdeveloped cortex, which is crucial for reasoning. Adolescents who experience the highest rates of trauma are 100 times more likely to commit murder than the general population.

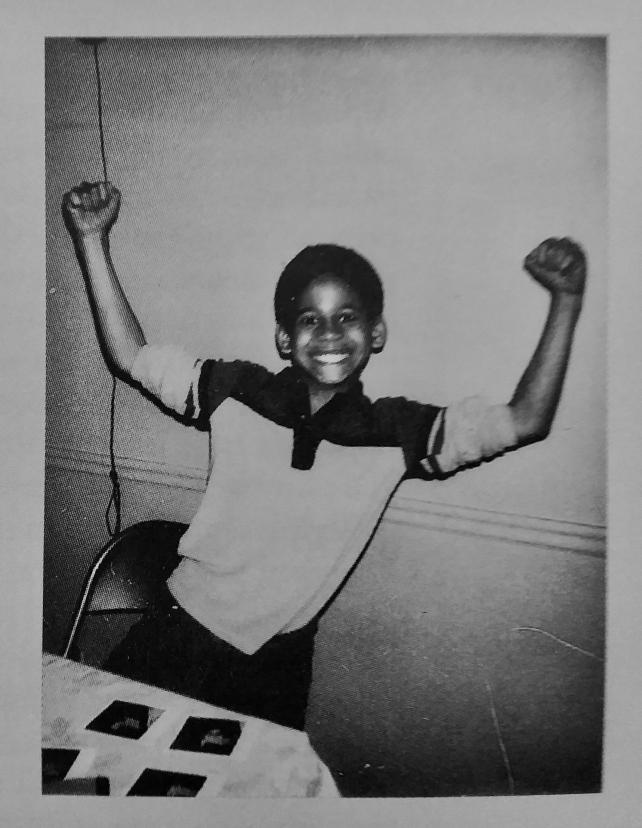

Espree as a kid

Courtesy Antonio Espree

Once a person’s brain matures in the mid-20s, their likelihood of committing a crime diminishes. “Only about 10 percent of serious juvenile offenders become chronic adult offenders,” Stapleton noted in his affidavit. Of the 150-plus juvenile lifers freed in Pennsylvania in recent years, not a single one has reoffended, according to data from a nonprofit law firm.

By his mid-20s, Espree was tired of getting in trouble and being put in solitary. “I really wanted to learn to think for myself,” he says. He earned his GED certificate and enrolled in college classes. “He is a deeply contemplative person,” reflected Micol Seigel, a professor at Indiana University who corresponded with Espree through letters about the books he was reading, books with titles like The Power of Intention and Man’s Search for Meaning, as well as works by Martin Luther King Jr. and Kahlil Gibran. “The more educated I became, the more positive I became,” Espree says.

Later he launched music therapy and mentorship programs for younger inmates. He also prepared dogs for adoption at the prison. “That he has developed under the adverse circumstances of incarceration truly is a testament to Antonio Espree’s character and the indomitable nature of his spirit,” Judge Darlene O’Brien wrote in support of his petition for parole in 2016. She also said that while she doubted someone in his shoes could transition well on their own after so many decades in prison, living with his cousin would give him “every chance of succeeding.”

Espree was lucky, says Cuauhtemoc Mexica, a postdoctoral researcher at Arizona State who spent more than seven years in juvenile detention himself for violent crimes committed as a teen. “A lot of people, when they go down young and they’ve been down for more than a decade or two decades, they tend to lose touch with most family members,” Mexica says. “Imagine going from a setting like that and then back into society.”

When Espree walked out of the G. Robert Cotton Correctional Facility on April 6, 2017, he looked up at the sky and took deep breaths of the fresh air. “He was in disbelief,” says Meagan Dreher, a paralegal who had come to meet him. He went to a restaurant to order French toast and reflected on how strange it was to cut with a fork and a knife after decades of using a prison spork. The next day, he stopped at a Catholic high school, where he wanted to thank a group of students who had written a legal brief on his behalf. A lot had changed since the 1980s: He had never used a cellphone. Even supermarkets were overwhelming; the first time he went shopping, he asked whether he could pick up a tomato to inspect it before buying it.

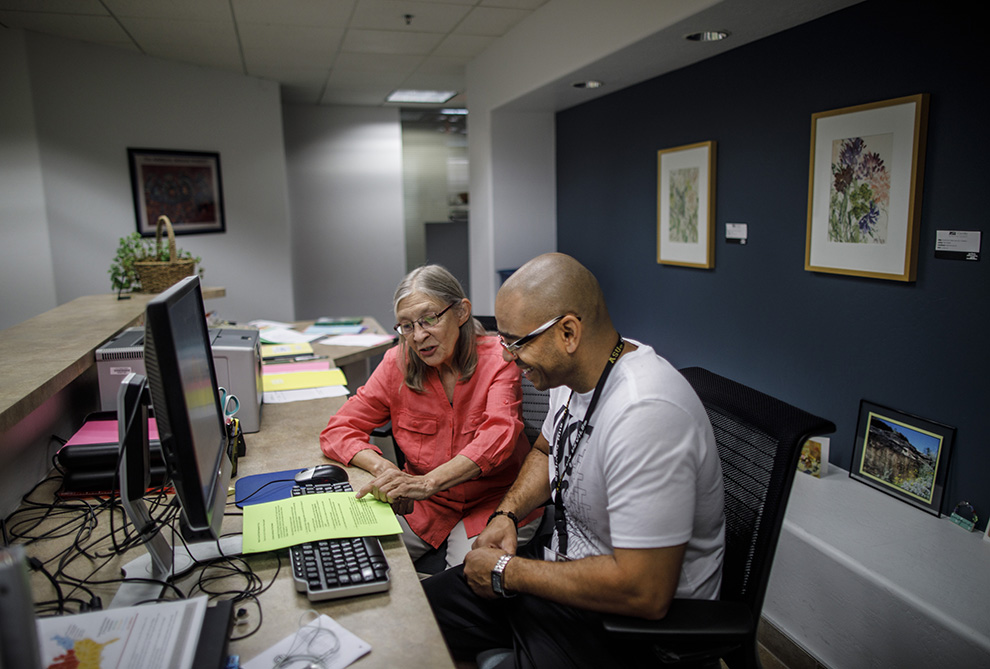

Espree works for the Arizona State University Lodestar Center for Philanthropy and Nonprofit Innovation with his supervisor, Dr. Peg Bortner. The on-campus center helps incarcerated women take college classes.

Barbara Davidson

Weeks later, he owned little more than a suitcase of legal documents and clothes and a bag filled with gifts from the Catholic school—socks, rosary beads—when he moved to Phoenix. Bailey, a tenured professor, helped him enroll at Arizona State University and let him share his bedroom and even some of his clothes.

Many others in Michigan may never get that chance. About an hour and a half from where Espree was incarcerated, Judge Jessica R. Cooper sentenced some of Oakland County’s juvenile lifers decades ago. Today she’s the local prosecutor. After the Supreme Court decisions, she requested renewed life-without-parole sentences for 44 of 49 of them. One of those lifers is Kevin Boyd, who’s now a 41-year-old inmate at Thumb Correctional Facility in Lapeer.

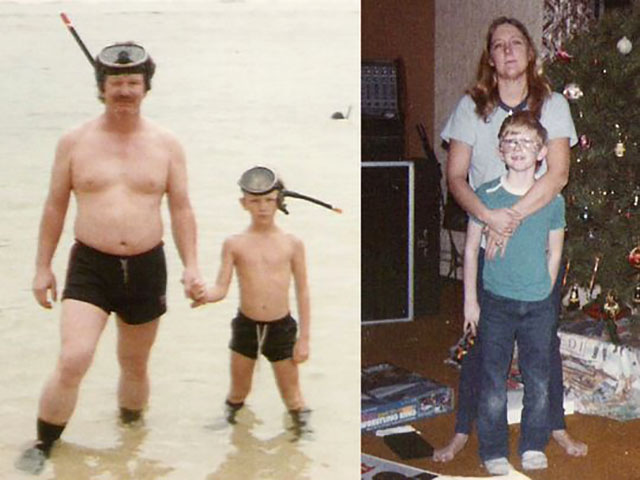

When Boyd was 16, his dad punched him in the face during a fight about changing schools—he cycled through 10 because of his parents’ divorce. When his mother and her girlfriend found out, they told Boyd they wanted revenge and asked for the keys to his dad’s apartment. Boyd handed them over, and the next day his dad was dead with more than 20 stab wounds. His mom confessed and was sentenced to life without parole; so was Boyd.

Kevin Boyd with his father, Kevin Sr., and his mother, Lynn.

Courtesy Kevin Boyd

According to Boyd’s lawyer, the jury never determined whether he participated in the stabbings. “No matter what Kevin’s role in the death of his father, he was acting at the behest of his mother,” his lawyer David O’Brien argued last year after Cooper asked a court to resentence him to prison for life. “That key fact places his vulnerability as a child, and more particularly a child looking for parental approval, at the centerpiece of the crime…Kevin’s case is literally the textbook example of why Miller invalidated life-without-parole sentences for juveniles.”

For more than a year, Boyd’s case stalled, along with 235 other juvenile lifers for whom prosecutors had requested renewed life-without-parole terms, as the Michigan Supreme Court reviewed procedural questions about resentencing. A ruling came this June, making it much easier for judges to hand out life-without-parole sentences to children in the state.

And while Miller v. Alabama outlawed mandatory life-without-parole terms for kids, it didn’t do much for people like Cyntoia Brown, who killed a middle-aged man when she was 16 after he brought her to his Tennessee home for sex. A federal judge ruled her mandatory life sentence was constitutional because it included the option of parole—a state court recently decided she’ll be locked up for at least half a century.

Nor did Miller help the 600 people serving discretionary life sentences with no chance of parole for crimes they committed as kids. In Louisiana, more than half of juveniles convicted of murder since 2012 have received such sentences, most of them African American.

Nationally, black teens are much more likely than white teens to receive these sentences. Before the Supreme Court made its ruling on the matter in 2012, about 61 percent of teens sentenced to life without parole were black. Since then, 72 percent of them have been black. “Now sentencing judges have discretion, and that discretion is used to disproportionately penalize kids of color,” says Heather Renwick, the legal director at the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, which wants the Supreme Court to ban life sentences without parole for teens altogether. Lawsuits are pending in Michigan to do just that.

As Boyd waits for a decision in his case, he tries to keep himself calm by lifting weights and jogging, which he liked to do as a kid. He’s grateful for the prison track but dreams of running in a straight line again. “You just kind of get tired of walking in that same circle,” he says.

Espree thinks often of Emanuel Billups, the man he killed, and of his family members. He keeps a copy of the affidavits they signed in support of his parole. The day before his birthday, he pulls them out. “Because I grew up without a father…I suffered emotionally and felt a lot of anger and hate,” Billups’ daughter, Shinetta Hudson, wrote. “I believe Tony is genuinely sorry for the suffering he has caused…I encouraged Tony to call or write to me, so that we both can continue to heal.”

When “Shinetta forgave me,” says Espree, it was “a feeling beyond anything. A part of what I do reflects that, continuing to keep my word to my victim’s daughter and victim’s mother and making sure that my actions out here are accountable to that and to them.”

With Bailey’s help, Espree enrolled as a justice studies major at Arizona State and applied for financial aid. After his first semester, he had a 3.29 GPA. He works for a philanthropic center on campus that helps incarcerated women take college classes, and he speaks regularly about juvenile justice. Fellow students sometimes mistake him for a professor—he shaves his head bald and almost always wears a button-down shirt and a tie along with his university lanyard.

On February 21, his birthday, I accompany him on a stroll past the library and students tossing a Frisbee on the lawn. Later, we stop by a nearby convenience store, where he buys a lottery ticket. He does this every Wednesday and Saturday, always using the same combination of cell numbers and digits culled from his incarceration. “If I won—when I win—I’ll be in a position to help folks,” he says. He’ll buy his cousin a new car, launch a nonprofit for at-risk youths, pay rent for Finley—so she can get her own place—and send his attorney on a trip around the world. He dreams of living in a house in Sedona with two Akita dogs.

With the lotto ticket tucked away, he goes to see Black Panther for the second time, leaning back in the theater’s cushy reclining seats. Afterward, he and Bailey drive to a restaurant called NYPD Pizza. Back at the apartment, before bed, Espree goes to the roof again. Nearly a year after leaving prison, he still struggles to fall asleep most nights. “I try to rest my mind, like I close my eyes, but there’s so much going on,” he says. “You know I’m seeing life, all life, I’m just seeing everything. It’s like I can’t miss it. You know, I can’t miss a moment.”

This story has been updated.