Nicole’s 30th birthday came and went in Chicago’s Cook County Jail. It was November 2017, and she’d been brought there more than a year earlier after relapsing into drug addiction. She knew her 11-year-old son missed her, but at least she was getting some treatment. “I’ve been diagnosed with ADD, bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety disorder, borderline personality disorder, impulse control disorder,” she explained, her straight, dark hair so long it practically reached her waist.

Chicago’s Cook County Jail is the biggest single-site jail in the United States. It’s also one of the biggest mental health care providers in the country. About a third of the jail’s 6,000 or so inmates have been diagnosed with a mental illness, and many of them were sent to the facility after the state reduced funding for hospitals and community caseworkers during the economic recession. Between 2009 and 2012, Illinois slashed $113.7 million from its budget for mental health services, causing at least two state-operated inpatient facilities and six Chicago clinics to close. Two-thirds of nonprofit agencies that offer mental health care in the state say they’ve had to cut back on their programs. With fewer services available, more people struggling with psychosis have been pushed into the streets. Most of those who are now housed in the jail were brought in on charges of nonviolent crimes.

Motivated by the growing mental health crisis, photographer Lili Kobielski set out in 2015 to capture portraits of the inmates, now compiled in the book I Refuse for the Devil to Take My Soul, which was released in December and includes transcripts of their interviews, plus poems they wrote during their incarceration. Working with the Vera Institute of Justice, she spent time with Nicole and a diverse group of detainees, in addition to a social worker and other staffers at the jail. Each portrait was a collaboration between the inmates and the photographer, who asked how they would like to be portrayed. (Surnames have been withheld for privacy.) Many spoke of childhood trauma and abuse, of the struggle to escape rough neighborhoods.

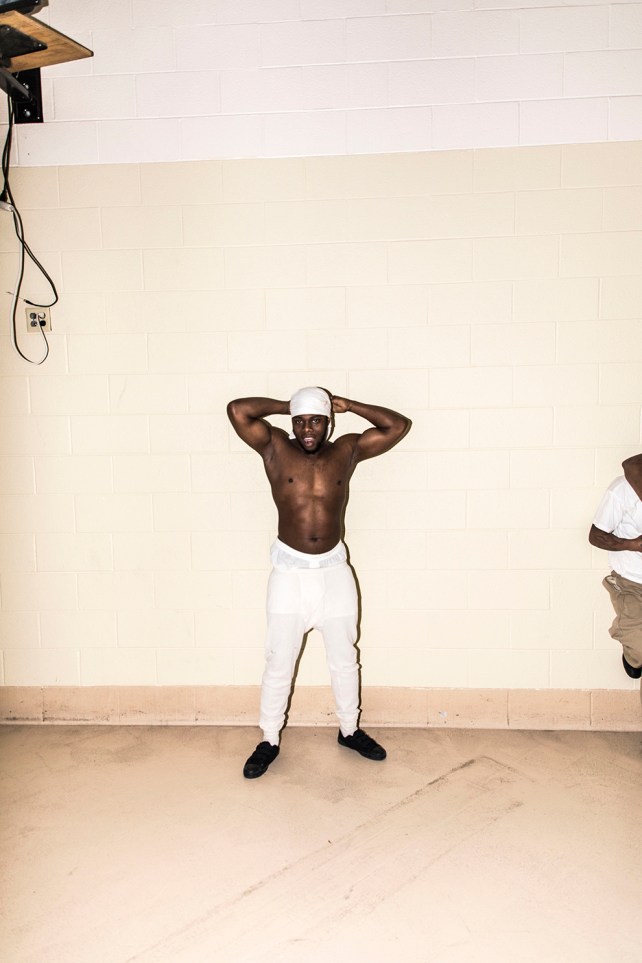

“I watched someone get killed when I was seven years old, shot when he was in the swimming pool,” Marshun, 33, who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and charged with aggravated robbery, told Kobielski. Of the jail’s medical staffers, he added, “When I first got here I thought these were the nicest people I ever met in my life.”

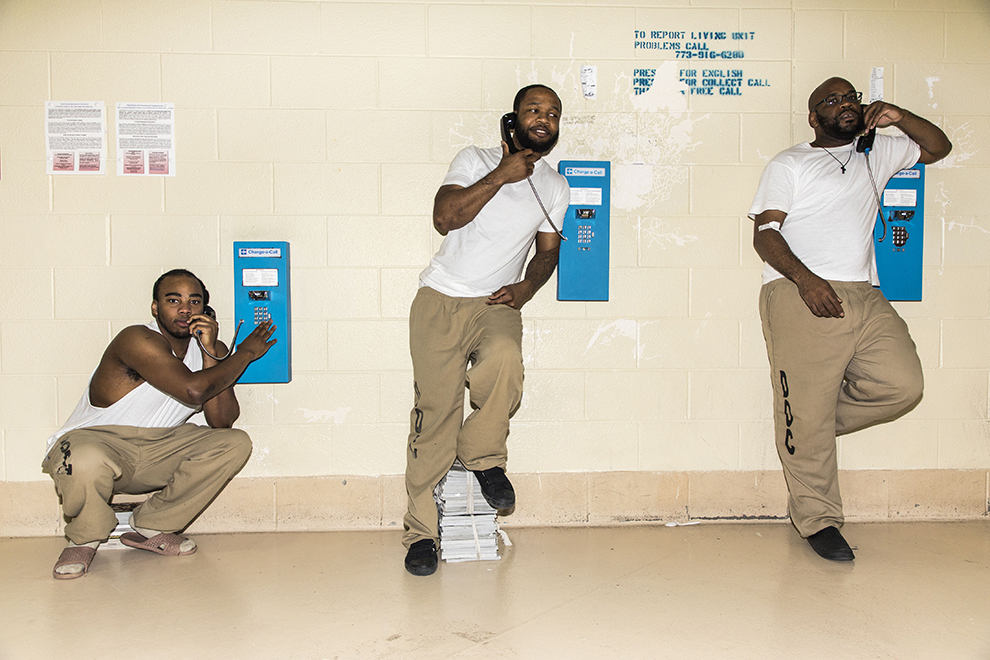

Division four, a “program tier,” offers classes and treatment to its occupants. Detainees in this program are not confined to cells but are allowed to spend their days in the tier’s large common area.

Lili Kobielski

Inmates in division four have about an hour of outdoor recreation time per day. Inmates in other divisions of the jail are sometimes not allowed outside at all.

Lili Kobielski

Chicago may be the biggest example of the mental health crisis in jails, but the problem there is not unique. Between 2009 and 2012, state legislatures around the country cut $4.35 billion in services for people with psychiatric problems, even while the need for services increased. Today, roughly 2 million people with serious mental illness are booked into jails each year, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness. That’s about the population of Houston, the fourth most populous city in America. In 44 states, jails or prisons care for more mentally ill people than hospitals, according to the Cook County Sheriff’s Office.

Marshun had been at the jail for 19 months when this photograph was taken. “When I get out I’m going to motivational speak. I know that’s my calling… I don’t want to hurt no one.”

Lili Kobielski

In Chicago, Sheriff Tom Dart has tried to adapt: Jail staffers now receive dozens of hours of mental illness treatment training. The facility’s Mental Health Transition Center offers individual and group therapy, while a Supportive Release Center helps people get back on their feet by providing food, clothing, access to showers, and referrals to resources for longer-term care.

Compared with healthy detainees, it can cost three times as much to jail someone with a mental illness. “It is far more expensive to try to manage mental illness and handle incarceration at the same time,” Elli Petacque Montgomery, a social worker at the jail, told Kobielski, adding that offering therapy in a detention facility is often extremely difficult and sometimes “countertherapeutic.” “Some people might need to address post-traumatic stress disorder or their anxiety, their depression, their substance abuse—they’re not going to get that in a jail setting. It’s just not going to happen.”

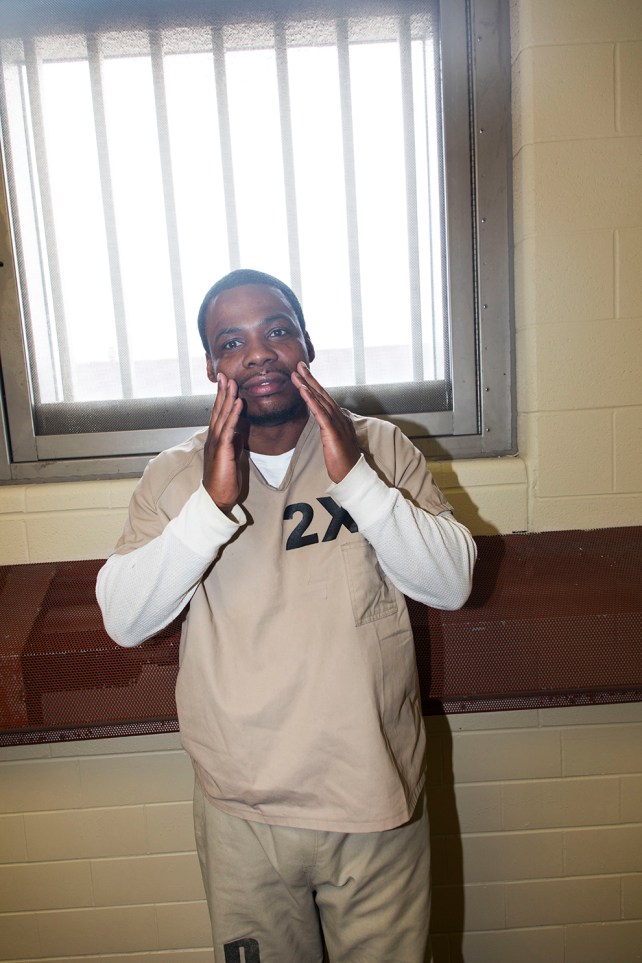

Many of the inmates are struggling with substance abuse disorders. Janay, photographed below, turned to alcohol when her boyfriend was jailed, leaving her with financial concerns. A mother of two, she was charged with reckless homicide after blacking out and getting into a car accident. “I’m the only one that made it out alive,” she told Kobielski.

Janay had been at the jail for eight months when this photo was taken. “Today we ‘wrote a letter to our addiction…’ It was like a breakup letter to alcohol. I said, ‘I’m taking my life back and you will no longer have the power over me. I can’t believe I allowed you to treat me this way. I thought you loved me the way I loved you.’”

Lili Kobielski

Inmates are escorted to a photography class. The jail has a variety of programs that aim to improve quality of life, treat mental illness, and reduce recidivism.

Lili Kobielski

Nicole: “This program has been amazing. It’s been really good. I’ve made some really big strides in my recovery here.”

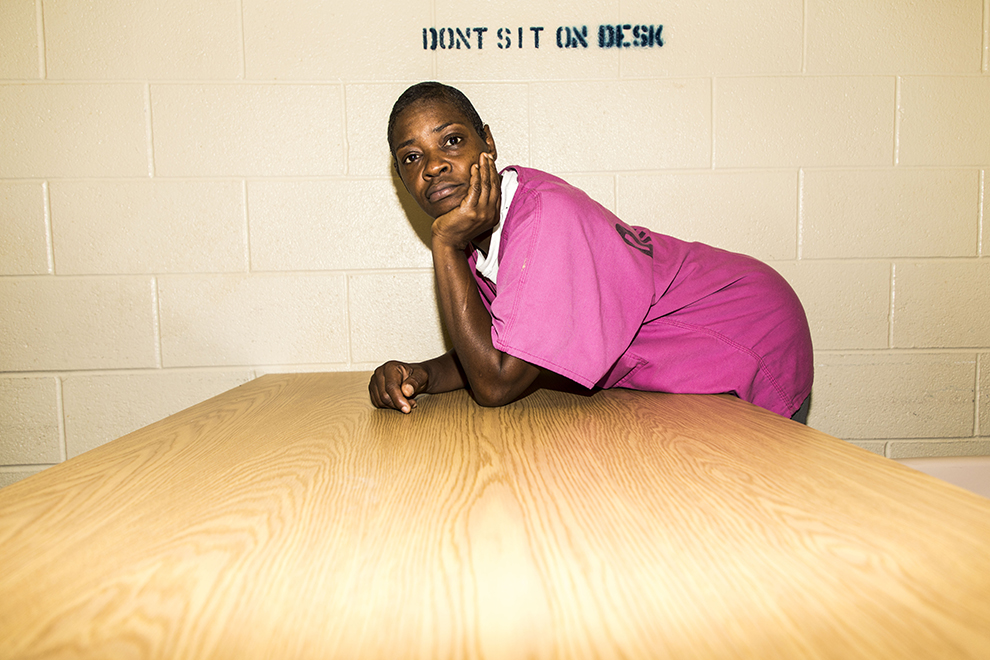

Theresa, photographed below, stole to support her crack addiction. Only 10 of her 15 children are still alive; she wishes she could be there for them. She dreams of going back to school—she didn’t start her education until she was 11 because she had to babysit her brothers, and she dropped out at age 16. “I’m just going to take one step at a time.”

Theresa: “I started using drugs at the age of 22. I went down an alley where all the rats and garbage is at and I didn’t come out until I was 36.”

Lili Kobielski

Milton, another inmate, was born on Chicago’s South Side but spent some of his early years in rural Alabama. He moved back to the city with his older sister after his parents died when he was still young. He has since cycled in and out of jail and says he isn’t exactly sure which disabilities he’s been diagnosed with. He wishes the state would spend more money on community services: “You got these jails, and you can’t do nothing, can’t control nobody,” he told Kobielski. “If they start helping the community more, put more useful things in, neighborhood things, it might be different, change. You don’t have basketball courts in the neighborhood no more. You don’t have help keeping them up. Instead of the guns and the policing—you could put a baseball diamond up, teach them on their baseball field.”

Milton sleeps in his bed in division two, where occupants have dormitory-style bunk beds instead of cells and receive therapy and medication.

Lili Kobielski

An inmate in division four

Lili Kobielski

Flags fly over an entrance to Chicago’s Cook County Jail.

Lili Kobielski

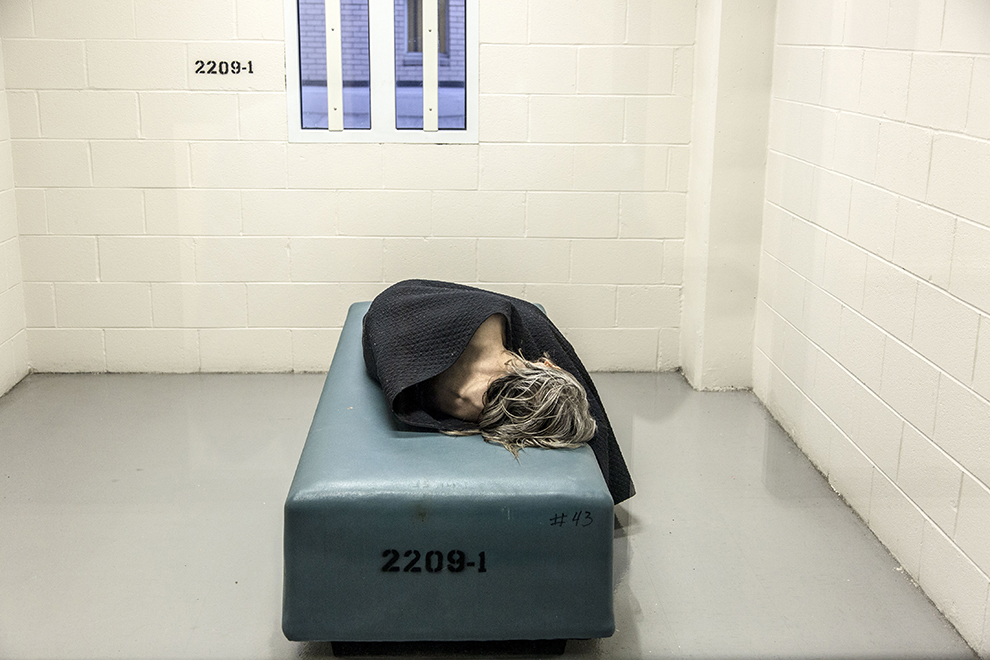

A woman sleeps in an isolation cell located in a section of the jail reserved for severely mentally ill inmates.

Lili Kobielski

Russell, 27, had been in jail for three years when he met Kobielski. He recalled the gang initiation he underwent at age 12. “I had to take a two-minute beating. At first it felt…it’s weird to say, it felt good, like I was part of something. I wasn’t getting…I don’t mean to sound soft or anything, but I wasn’t really getting the love I was trying to seek at home,” he told her.

Dywane, the 19-year-old in the final photograph, was jailed after law enforcement found weed, cocaine, and a gun at his dad’s house—he said he was facing 15 to 30 years in prison if convicted. He wants to move to Indiana, where his mom lives, but says he hasn’t been able to because of probation. “I hate Chicago, I want to get out of here so bad,” he told Kobielski.

Russell also wants to escape his old neighborhood and the pressure of his gang: “Even though you don’t want to be a part of that no more, there’s still people from the other side who still think that you’re part of it…”

Lili Kobielski

Dywane says he has severe ADHD and a reading disability. “I never in my life want to come back here…I don’t get along with the guys in here. I just sit in a corner by myself.”

Lili Kobielski

All photographs and quotes in this post are from I Refuse for the Devil to Take My Soul: Inside Cook County Jail (powerHouse Books), by Lili Kobielski.