In February 2018, in a small courtroom in rural Louisiana, an Eritrean man was fighting an impossible battle. The man, whom I’ll call Abraham—he asked that his real name not be used—was trying to convince immigration judge Agnelis Reese that he should receive asylum in the United States. He told Reese he had been imprisoned for 12 years in Eritrea for refusing to complete his military service, and tortured—not only beaten but sexually assaulted. “What do you mean?” Reese asked.

Abraham, who did not have a lawyer, told Reese he was too ashamed to share what he had been through. She pressed him. “I’m not trying to force you,” she said, according to a transcript of the hearing, “but this type of harm would be important to your case.” With his future at stake, Abraham explained how two Eritrean prison guards had covered his nose with plastic before at least one of them put his penis in Abraham’s mouth, at which point he passed out. “Did they do anything else that was sexual molestation?” Reese asked.

“They also inserted a stick in my bottom,” Abraham said. Reluctantly, he recalled being sodomized at least three times in a bloodstained room “intended for suffering.”

When Abraham mentioned that he was a Pentecostal Christian and that his status as a religious minority had contributed to his mistreatment in Eritrea, Reese pounced. During an initial interview with an American asylum officer, Abraham had not mentioned being sexually assaulted. “When you lied to the asylum officers or failed to disclose your sexual abuse,” Reese asked, “what do you think Jesus thought about that?”

“I did not lie,” Abraham replied.

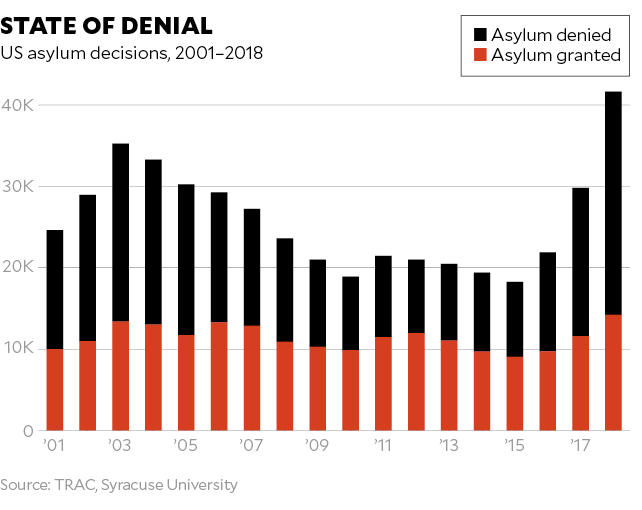

Reese rejected his asylum claim on narrow technical grounds. Abraham had stated, correctly, that the Eritrean government effectively controls the state church. Yet, Reese wrote, he did not produce documentation for this fact. Even if he somehow had been able to satisfy this requirement, Abraham probably never had a chance. Between 2011 and 2018, Reese denied every single one of the more than 200 asylum claims she heard.

Asylum seekers come to the United States prepared to tell stories of persecution, fear, and torture, but their fate often depends less on their credibility than on luck. Those who make it across the border are sent to detention facilities around the country overseen by Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Asylum seekers with relatively good fortune might end up in Elizabeth, New Jersey, where they have a 44 percent chance of being granted asylum. For those who are released from detention and have their cases transferred to New York City, it’s almost 80 percent. The less lucky ones get locked up in Louisiana, where immigration judges reject 84 percent of asylum claims. And the least fortunate find themselves at the Oakdale Immigration Court before Reese, America’s harshest asylum judge.

On paper, Reese might seem like someone who would be sympathetic to the challenges facing persecuted minorities: She’s a black woman, a Clinton administration appointee, a registered Democrat, and a preacher. But her unforgiving reputation precedes her. Theodore Tonka, a Cameroonian who sought asylum in 2017, recalls other African asylum seekers telling him to pray he wouldn’t get Reese. “If this woman is to hear your case,” he remembers one saying, “you are going back home.” Tonka started to believe them when an attorney he hoped would represent him said she didn’t want to waste her time with Reese. After the judge rejected his claim, “I left with the same impression that everyone else had,” Tonka said. “She’s evil.” Two attorneys I spoke with compared Reese to the devil; one called her “Satan incarnate.” (Reese, reached by phone, declined to comment.)

When deciding asylum cases, immigration judges are supposed to impartially weigh the evidence presented by the asylee and the Department of Homeland Security. (Asylum seekers are not guaranteed an attorney.) But a review of transcripts from six asylum hearings and a visit to her courtroom showed that Reese often acts like the federal immigration prosecutor she was before she was named an immigration judge in 1997. She lays traps, twists respondents’ words against them, and uses the intricacies of immigration law to ensure that her decisions are nearly impossible to overturn on appeal. Al Page, the lawyer who handled Abraham’s appeal for a pro bono legal group, says Reese doesn’t try to learn whether people are deserving of asylum: “She’s entering the situation with the intention to prove that they’re not.” DHS prosecutors remain almost entirely silent in Reese’s courtroom. Jeremy Jong, a lawyer with the Southern Poverty Law Center who has appeared before Reese dozens of times, has watched prosecutors browse for clothes online while Reese does their jobs for them.

Unlike some judges, Reese doesn’t often make small talk with immigration attorneys, and the lawyers I spoke with knew little about her personal life. Alvin Sharp, a fellow judge and pastor in Louisiana, grew up near Reese in rural northern Louisiana. They became friends at Southern University Law Center in Baton Rogue in the late 1980s, where he was struck by her seriousness. In law school, while Sharp and his other friends might spend an evening eating wings at Hooters before cramming all night, Reese would be in bed by 10 o’clock, he says. When complex legal issues came up, people would turn to Reese, saying, “Agnelis, break it down.” Sharp remembers a meeting where Reese and another member of their study group disagreed about what to do next. Reese prevailed after Sharp said, “We bow to the queen.” The nickname stuck.

When Sharp turned down a job as an immigration prosecutor in Oakdale, he recommended Reese, who got the position. To the best of Sharp’s knowledge, Reese has never been married or had kids. He’s never seen her in a relationship, either.

At the pulpit, Reese is far more animated than in court, but her no-nonsense style remains apparent. In a Palm Sunday sermon posted to Facebook in April, Reese related a New Testament story about Jesus overturning the tables of the money-changers he believed were polluting the temple with commerce. She compared his actions to something her parents would tell her as a kid: “It’s my house. And my rules…And if you don’t want to do what I say, you got to go.” She seems to apply the same dictum to her courtroom.

Reese’s fiefdom in Oakdale lies about 200 miles from both Houston and New Orleans. The former lumber town’s main industry these days is incarceration. Along with cells for more than 2,000 inmates at two low-security federal prisons, there is room for more than 1,000 immigration detainees at the Pine Prairie ICE Processing Center, a razor wire–wrapped fortress run by the GEO Group, the nation’s largest private prison company. The Oakdale immigration court is located next to one of the low-security prisons.

On a weekday morning in June, immigration attorneys Rachel Chappell and Christopher Kinnison were waiting in the court’s small lobby, overseen by two GEO guards. When Chappell told Kinnison that she was there for an asylum hearing with Judge Reese, Kinnison half-joked that the only point of showing up was to hope that Reese made a mistake that justified an appeal. Kinnison, one of the few immigration attorneys based near Oakdale, had never argued an asylum case before Reese. “I tell all of my potential clients who have her that they will lose their asylum case,” he says, “and that they shouldn’t pay me thousands of dollars for them to get the same result.” (Oakdale immigration judge Johnny Duck, a 69-year-old white Reagan administration appointee who sometimes removes his prosthetic leg during hearings, grants a relatively charitable 16 percent of claims. A third judge started there last year, but his case record is not yet publicly available.)

Chappell’s client that morning, Simranjit Singh, a 22-year-old Sikh from India, did not give her much to work with. Asylum seekers without convincing claims are sometimes coached by smugglers to tell stories designed to improve their odds, and Singh’s tale was a familiar one. In the lobby, Kinnison correctly guessed its details, down to the number of beatings Singh had allegedly suffered at the hands of members of India’s main opposition party.

Singh appeared in Reese’s court in an orange jumpsuit and a navy blue turban. He remained shackled at the ankles, waist, and wrists throughout the hearing and struggled to manipulate the handcuffs when Reese asked him to sign a form. Reese appeared in a black robe. Her courtroom’s walls were bare aside from the seal of the Justice Department, which runs the nation’s immigration courts.

When it came time to question Singh, the government prosecutor, Michael Smith, made a few inquiries about Singh’s passport before turning things over to Reese. The judge picked apart Singh’s story for the next 40 minutes. She appeared incredulous that Singh’s travel to the United States, which cost his family about $30,000, had been arranged by an uncle. “You are an adult, correct?” she asked. After a brief recess, Reese took a swig from a coffee mug before dictating her denial of Singh’s asylum request to the court reporter, down to every semicolon. When advised of his right to appeal, Singh began shaking his head to signal that he didn’t want to.

It’s not that Reese doesn’t believe everyone who appears before her; it’s that she believes almost nobody. Immigration judges may decide that an asylum seeker told the truth but doesn’t face enough risk back home to justify being granted asylum. But Reese usually rules that asylees’ stories aren’t credible, according to eight attorneys who have appeared before her. That can make it nearly impossible to overturn her decisions, since the conservative 5th Circuit Court of Appeals grants judges in the South extreme deference when it comes to evaluating asylees’ honesty. (ICE has taken advantage of the difficulty of appeals in the region by more than tripling its detention space in Louisiana since February. Donald Trump’s Justice Department has sent six new immigration judges to rural Louisiana.)

Abraham was no exception. After Reese found his story of persecution in Eritrea not credible, his appeal failed in October. But he was luckier than most asylum seekers who go before Reese: His home country refused to take him back. So in late June, after 20 months of imprisonment, ICE was forced to release him. He is a free man—for now. ICE knows where he lives and can arrest him if Eritrea allows him to be deported.

He still struggles to make sense of how he ended up before Reese. “I ran away from dictator in my country,” he says in English. “I come to face a dictator in a courtroom in America?” But he doesn’t wish her ill. The book of Matthew, he says, tells Christians to “love your enemy…and pray for those who persecute you.”

The Gospel, Abraham says, “was talking about Judge Reese. I never hated her. I prayed for her heart to come back.”

Tonka, the Cameroonian asylum seeker, who fled to India after being deported, expresses the same sentiment. He prays that “God will touch her heart, if she’s a human being,” and he hopes that Reese will one day “think about the lives that she has destroyed.” She now has plenty of time to reflect on her unbroken streak of denials: Nine days after I visited her courtroom, Reese stepped down from the bench after 22 years. For the asylum seekers at Oakdale, any change of heart would come too late.