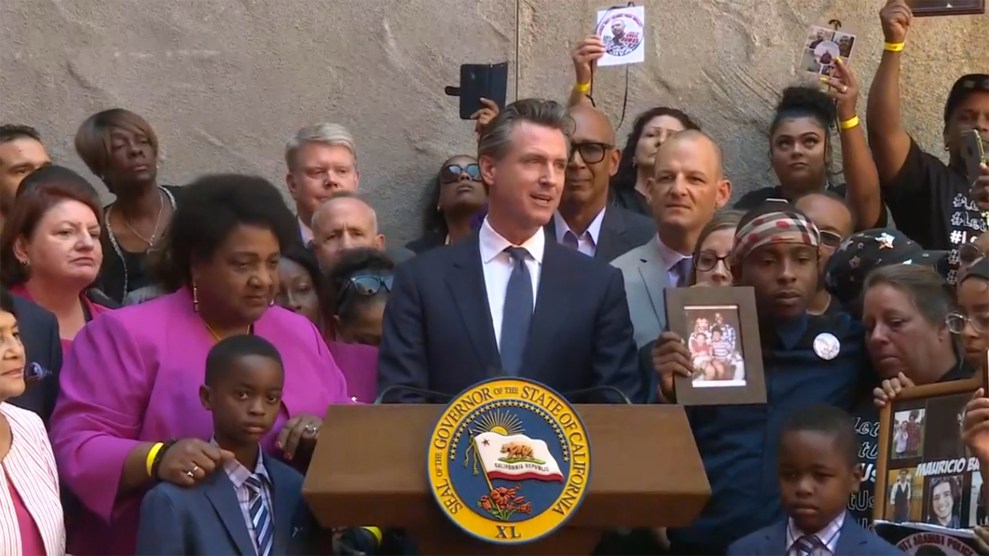

California Gov. Gavin NewsomAssemblymember Shirley Weber/Facebook

California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed into law one of the country’s most substantive police use-of-force bills on Monday. The legislation nominally attempts to narrow the parameters for when officers are allowed to use deadly force on the job—marking a significant turning point for the state, which is the country’s most populous and home to more officer-involved shootings than almost any other. However, multiple critics, including advocates who work on behalf of victims’ families, argue the final bill has been watered down by powerful police unions and is far from the comprehensive reform they had hoped for.

“Originally, it was that police were required to exhaust all other measures before using deadly force,” said Melina Abdullah, a professor at California State-Los Angeles and co-founder of Black Lives Matter Los Angeles. “And now, that’s the intent of the bill, but it’s not in the bill statute itself.”

In an interview with Mother Jones on Friday, Newsom said the bill “is about saving lives, it’s about trust, it’s about community. It’s about addressing one of the most vexing issues that persists in communities all across America. And that’s the relationship between law enforcement and our diverse communities, particularly though not exclusively the African American community.”

The new law updates California’s long-standing use-of-force statute, which has been on the books since 1872 and was the oldest, untouched use-of-force law in the country. Nationally, use-of-force policies have drawn widespread scrutiny in recent years as more deadly interactions with police have been caught on camera and publicized. But there’s still no uniform policy that every police department in the country is required to follow. Instead, department policies vary from city to city and state to state.

Previously, California police officers, like officers in most states, could use deadly force if it was deemed “reasonable,” meaning a reasonable officer would have acted a similar way. The new law requires California officers to only use deadly force if it’s “necessary” to protect against an imminent threat of death or serious injury. Under the Obama administration, Seattle and San Francisco adopted a standard similar to the one in California’s new law, and their instances of deadly force dropped.

One of the main drivers for the change in California was public outrage over the police killing of Stephon Clark in Sacramento last year. Officers fatally shot Clark, a 22-year-old black man, while he was standing in his grandparents’ backyard and holding a cellphone, which police said they mistook for a weapon. Federal and state prosecutors declined to press charges against the officers, arguing that they were afraid for their lives and thus acted legally. The killing and lack of charges sparked protests in Sacramento and drew national attention. The bill is now being called “Stephon Clark’s law” by lawmakers.

“[This bill] is likely to save lives and significantly reduce police violence in the state. Use-of-force policies have a direct impact on the likelihood that police will use force, including police shootings,” said Samuel Sinyangwe, a data scientist who co-founded the initiative Campaign Zero to bring attention to use of force. “These are the rules of engagement for police officers.”

But critics argue the bill fails to define what “necessary” actually means, leaving it up to the courts to decide. Previous versions of the bill included a definition of the term, but it was reportedly removed from the bill to appease law enforcement. “Even though it maintains what they call a ‘necessary’ standard, that necessary standard is to be determined by the reasonable officer,” said Abdullah of Black Lives Matter Los Angeles. The original bill, which was once supported by Black Lives Matter and a number of other community-led organizations, such as the youth-led community group Silicon Valley De-Bug, explicitly required officers to exhaust all measures before resorting to deadly force.

Newsom responded to the criticism in our interview by saying the bill is “certainly top-tier,” though “there’s aspects of this, I imagine, that still fall short. I’m not naive about that. But we’re certainly now at the leading edge of use-of-force legislation, and I am proud of that and I think that’s long overdue in California.”

Black Lives Matter is also concerned about a separate bill, stuck in committee, that would provide more money to train police officers. Earlier this year, the backers of the training bill amended it so that it could only pass if the use-of-force bill passed, leading to reports that the two were linked. “For Black Lives Matter, we cannot support any legislation that in any way expands the police state,” Abdullah said. “We know that when they’re talking about training, that means more money into the departments, and we believe that the way to best ensure the public safety of people is to invest in things like mental health resources, to invest in things like livable wage jobs, housing, and the kind of things that actually make communities safe.”

California is the first state to combine a “necessary” standard for force with a requirement that courts consider an officer’s conduct leading up to a shooting, rather than just the moment it happened. For instance, in the case of Stephon Clark, a court could examine not only whether the officers feared for their lives at the moment they pulled the trigger, but also how they had acted beforehand, including when they first located Clark, after getting a 911 call about someone smashing car windows, and as they pursued him on foot to his grandparents’ backyard.

“Even with the amendments [removing the explicit definition of ‘necessary’], it’s still one of the strongest use-of-force laws in the country,” said Adrienna Wong of the ACLU of Southern California. She argues that courts will know how to interpret the necessary standard even without a formal definition in the law. “It’s pretty clear that the purpose of the bill is to limit deadly force to only when there is no other way to deal with this situation. That’s what ‘necessary’ means,” she said.

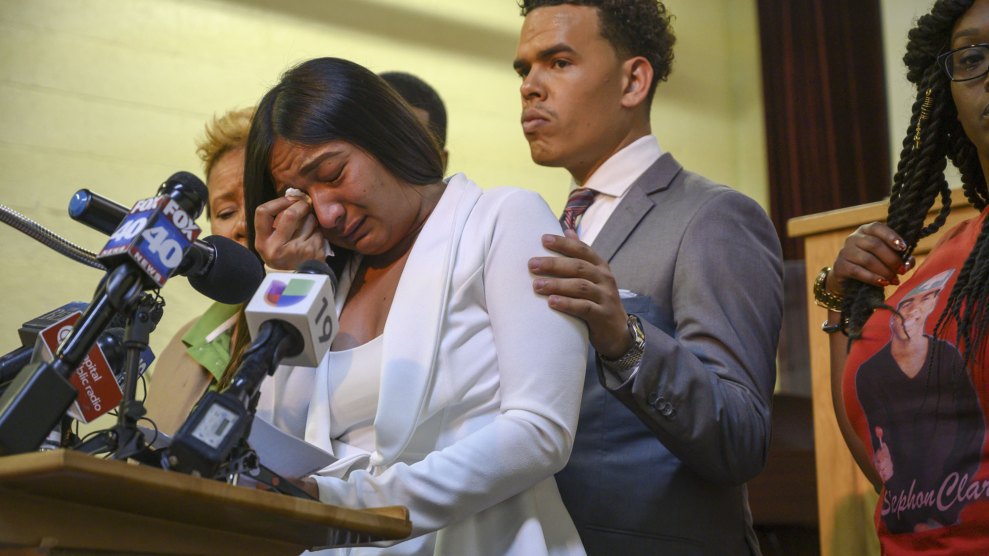

Along with Black Lives Matter, the family members of some victims of police violence withdrew support for the bill after the amendments were made.

Newsom insisted that the victims’ families were “completely determinative” in the bill’s crafting. “Had it not been for their faith and devotion to this cause, their tenacity, their personal stories, their tragedies, their perseverance and dedication to this, we wouldn’t be here,” he said. Clark’s brother, Stevante, has said that although the legislation was “a little watered-down with the changes,” in the end he sees it as a sign of progress. He’s also said, “At least we are getting something done. At least we are having the conversation now.”

And Jennie Ruiz, whose younger brother, Charles Salinas, was killed by the Sanger police in 2012, also supports the bill. Salinas, a 46-year-old military veteran with a history of mental illness, had called 911 and told a dispatcher that he had a gun but wouldn’t hurt anyone, and that he was suicidal. When officers arrived, they found him unarmed, standing in a flower bed. They shot at him 22 times, including after he had fallen to the ground. The family sued but lost their case, after officers argued that Salinas had moved toward them and that they thought he reached a hand toward his waist. “It just never sat well with me that these guys got away with what they got away with,” Ruiz said in an interview with Mother Jones.

“It’s a baby step, but it’s a step,” she added about the new law. “You’ve got your foot in the door now. Because there’s still lots more work to be done.”

Newsom similarly recognizes the bill isn’t a quick solution, but rather a step in the right direction. “All of us recognize that signing a piece of paper doesn’t change anything,” he said. “You got to change the culture, you got to change mindsets. You’ve got to implement. And so I’d say this: Give us the chance to prove ourselves, and hold us to account on the training work, the de-escalation work, the cultural work that is in front of us.”

“I can’t go to any more funerals,” he concluded. “I’m accountable.”