Rudy Coronado still refers to what happened as “that day.” He thinks about the signs he missed and the signs he saw but ignored. “That day—Carol was acting kind of weird,” he says. “She was just different.”

Not different in the way his wife had always been different—the simple, no-makeup, no-celebrity-gossip style that had charmed Rudy when he first met her. She loved books and worked hard. She was quirky, separating the rice and beans and vegetables on her plate and always eating all of one thing first. She was also precise and meticulous, something she’d honed in the military and applied to motherhood, keeping spreadsheets on all the daily activities of their three daughters: Sophia, 2, Yazmine, 1, and Xenia, 3 months. “Every time she breastfed, every bottle she gave them, everything was documented,” Rudy says. “Every time they pooped, how they pooped, everything. Everything.”

Listen to April Dembosky describe her yearlong investigation into how the legal and health care systems could better serve women who suffer from postpartum depression and psychosis on the Mother Jones Podcast:

But that day, May 20, 2014, was different. Carol, who was 30 at the time, woke up in a panic. She phoned her mom repeatedly, leaving one desperate, rambling message after another until the voicemail system cut her off. “Mommy, please call me. Please—please—please. I’m tired. I’m exhausted. I’m hungry,” she said in her first message. By the sixth, Carol sounded spent: “Mom. Please call me. I love you. Bye.”

By the afternoon, Carol was barely saying anything. When Rudy came inside after working on his ’68 Chevy truck across the street from their house in Torrance, California, Sophia was running around with no diaper on. There was poop everywhere—on her hands, on the carpet, on the walls. Carol was lying on the bed. Her eyes were blank.

Rudy started yelling at her. He said some things he now wishes he hadn’t. “I was like, ‘Carol—to what extreme is this going to get to?’ And I regret telling her that,” he says. “Because I don’t know if that’s what kind of sparked her to do something dumb. To do that.”

Rudy was back working on his truck when Carol’s mom came over. She went in the house and then ran back out, screaming.

All three girls were dead. Carol had taken a knife from the kitchen and stabbed each in the throat and through the heart. Then she laid them out on her bed, youngest to oldest.

“At first glance, it was weird, ’cause I didn’t see no blood. I don’t remember seeing blood,” Rudy recalls, his voice catching. “So when I walked up and I touched Sophie, she was cold. I was like, ‘What’d you do?’ I couldn’t believe my eyes.”

Carol looked at Rudy and told him she loved him. Then she pushed the knife into her chest.

The first time Carol heard about postpartum psychosis was after she was treated for a punctured lung, then taken to jail and charged with three counts of first-degree murder. The psychiatrists who treated her told her that she’d experienced a break from reality, caused by the hormonal changes from her most recent pregnancy, the lack of sleep, and the relentless cycle of breastfeeding and caring for children under 3 years old. “Everybody who saw her, all of the doctors, within hours and days of this event, found that she had some kind of a psychotic disorder,” says Diana Barnes, a psychotherapist who evaluated Carol in jail and testified as an expert witness in her trial. Carol’s bizarre behavior, her confusion and detachment, were all symptoms of postpartum psychosis.

Postpartum psychosis affects one or two out of every 1,000 moms after birth, according to international studies. In the United States, this translates to between 3,790 and 7,580 women a year, though many reproductive psychiatrists believe that is an underestimate because the symptoms are easy to miss and many OB-GYNs, pediatricians, and family doctors are not trained to recognize them.

“Postpartum psychosis often presents with delirium-type symptoms, mainly confusion, not classic hallucinations or paranoia,” says Nirmaljit Dhami, a psychiatrist in Silicon Valley who specializes in postpartum mental illness. The symptoms may wax and wane. While most women with postpartum psychosis experience symptoms in the first year after birth, if it is left untreated, the illness can linger for many years, Dhami says. “It shifts into a chronic, downward drift, similar to schizophrenia. Then women show up at the hospital and get admitted, usually because something extreme happens, like suicidal thoughts or complete inability to function.”

Women with postpartum psychosis often experience a mood disturbance such as mania or depression. Carol’s lawyer argued she had been depressed but that her doctors had missed that, too. Her primary care physician, Bijan Ghatan, testified at her trial that Carol didn’t “seem depressed” when he saw her six days before the killings. “She was her usual jovial self” during their brief visit, he said. When the defense asked if he’d asked Carol if she was depressed or had done a formal screening, he said no. In 2018, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists rewrote its guidelines to recommend that doctors providing obstetric care expand formal testing of all new moms for postpartum mental illness. Last year, California made the test mandatory, the fifth state to do so.

“When we enter an exam room, we always say, ‘Hey, you look great! Look at the baby! Yay!’” says Torie Sepah, a reproductive psychiatrist who treated Carol in jail and delivered many babies when she was in family practice. “That leaves no room for the mom to not be doing great. To say, ‘Actually, I’m really miserable. I’m up all night. My husband never helps me.’”

Many women with these feelings often think they’re bad moms. But with postpartum psychosis, those feelings of failure and inadequacy can become delusional: As many as 29 percent of moms who kill their kids also kill themselves, and researchers believe even more attempt suicide. “They start to believe that their children would be better off with them in heaven,” says Michelle Oberman, a law professor at Santa Clara University and an expert on infanticide. Carol Coronado’s doctors kept her on suicide watch for almost two years before and during her trial.

More than 100 women are currently in prison in California for killing their children, according to a review of thousands of court records and news reports by KQED. Forty percent of these women took their babies’ lives before they were 1 year old, the timeframe when most postpartum mental illness occurs. Nearly 70 percent are serving life sentences. It’s unclear how many may have suffered from postpartum psychosis because many cases never go to trial. Defense attorneys who don’t know about the condition may plead women down to a life sentence and call it a victory because they spared their clients from the death penalty, Oberman says.

In about two dozen countries, including Canada, Australia, Brazil, Sweden, Japan, these kinds of harsh sentences are rare. These nations have laws that treat infanticide as distinct and different from murder. Most of them are modeled after Britain’s Infanticide Act of 1938, which makes manslaughter the maximum charge a woman can face for killing her infant if “the balance of her mind was disturbed by reason of her not having fully recovered from the effect of giving birth.” Under the current interpretation of the law, “there’s an assumption that something was off,” Barnes says. “In many cases they don’t even go to prison.” Women who are found guilty are often sentenced to treatment, not incarceration.

The United States has no uniform legal standard for these kinds of cases. Laws vary by state, and judgments, which range from life without parole to probation, often depend on the sympathies of judges and juries. Most prosecutors portray women who harm their children as cold-blooded killers. After Carol was charged, the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office considered seeking the death penalty.

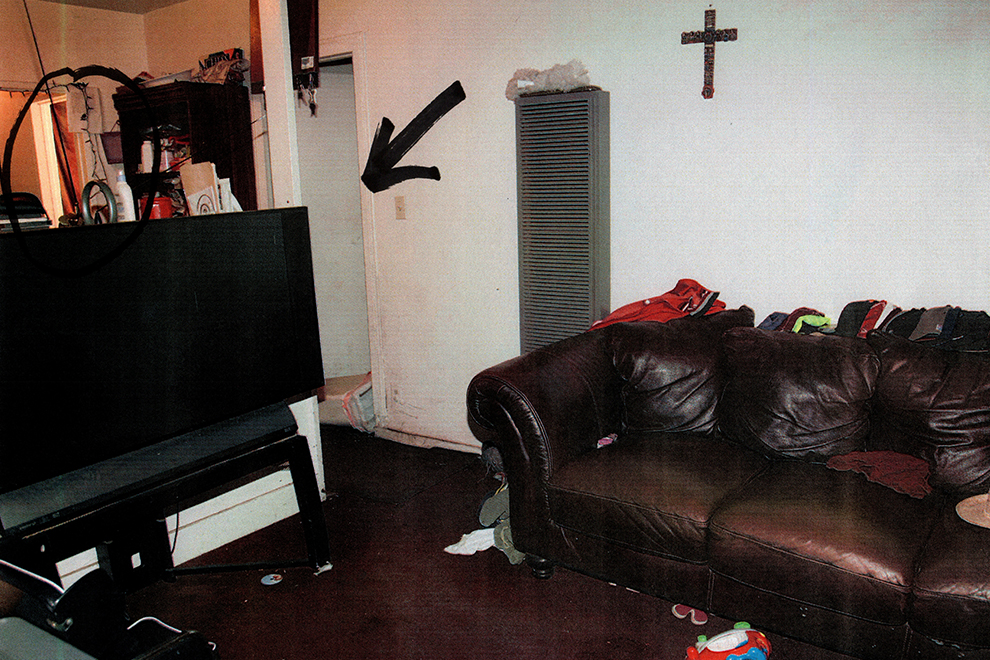

Photographs of Carol Coronado’s house entered as evidence in her murder trial

Compton Courthouse

Carol says she didn’t know what was going on most of the time she was in jail waiting for and attending her trial. She had no clue how the scar on her chest got there. “I had no idea where I was, what happened,” she says over a scratchy phone connection from prison. “They started filling in small details here and there, but never the full thing.” When her family called and Carol asked after the girls, her mother just said they were “gone.” Rudy told her they were “safe.” Carol figured they were at their godparents’ house or her sister’s house.

Though her doctors tried to tell her what happened, it finally sunk in when her lawyer gave her the specifics. “And I flipped out. I became hysterical and inconsolable. I was screaming,” she says. “I did not believe it.”

It’s common for people not to remember what happened during a psychotic episode, says Sepah. Carol says her memories stop about a week before the deaths. “That’s about the time my brain began to stutter and shut off, memory-wise. Before it completely broke,” she says.

She does remember having nightmares. “I was terrified to go to sleep. I wasn’t showering, taking a bath, brushing my teeth. I wasn’t eating. I wasn’t doing anything.” She couldn’t concentrate. She put socks away in the fridge and milk in the dresser. She felt overwhelmed, “like I was worthless, helpless, hopeless, and I’d be better off dead. That nobody needed me. That I was nothing.”

Her lawyer, Steve Allen, hired with money that Rudy managed to raise from a crowdfunding campaign, decided to pursue an insanity defense for the first time in his career. The odds were against him: The insanity defense is used in less than 1 percent of criminal cases, and only about a quarter of those attempts are successful. “It’s a very, very hard defense to make,” says law professor Michelle Oberman. “It almost never works in postpartum mental health defenses.”

The backlash to the insanity defense can be traced to 1981, when 25-year-old John Hinckley attempted to assassinate President Ronald Reagan. Hinckley said he was convinced that Jodie Foster would fall in love with him if he killed the president. Psychiatrists testified that Hinckley had schizophrenia, and a jury found him not guilty by reason of insanity. Americans were outraged: After the 1982 verdict, 83 percent said justice had not been done. Over the next few years, lawmakers in 38 states rewrote their insanity laws to make verdicts like Hinckley’s nearly impossible. (Hinckley spent 30 years in a psychiatric hospital and was released in 2016.)

Another case had soured many Californians on the insanity defense. In 1978, former San Francisco Supervisor Dan White shot and killed Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk, one of the first openly gay elected officials in the United States. White’s lawyer invoked California’s “diminished capacity” standard in the infamous “Twinkie defense,” which claimed White had been depressed and periodically obsessed with junk food, which compromised his ability to understand or control his actions. A jury found White guilty of manslaughter and he was sentenced to eight years in prison. Following the verdict, San Franciscans rioted outside City Hall.

In 1982, California voters passed a tough-on-crime ballot proposition that included an overhaul of the state’s insanity defense law. It did away with the diminished capacity standard, replacing it with a much stricter legal standard for insanity. This test, called the M’Naghten Rule, now used in 25 states, was first established in 1843. It sidelines a criminal defendant’s “mental disease” and instead focuses on her ability to differentiate between right and wrong. It’s a moral test, not a clinical one. “The test for proving insanity is so out of keeping with the way that we understand how the mind works,” Oberman says.

When Carol Coronado went on trial in November 2015, she still couldn’t remember anything from the day she killed her daughters. Even though this is common with people who have had psychotic episodes, it left a giant gap in her legal defense. To be found legally insane, Carol would have to prove that she didn’t know what she was doing was morally wrong. But she had no explanation at all for why she did what she did.

The prosecutor, Emily Spear, exploited this weakness, filling the void in Carol’s memory with her own narrative of what had happened. Spear, who was eight months pregnant at the start of the 12-day trial, claimed Carol’s motive was revenge. “The marriage was not a good one,” she said during her opening statement. “Finances were very, very tough.” Rudy was a jerk, she said, often leaving Carol in charge of three little girls with no help. Spear argued that Carol decided to get back at Rudy by killing their daughters. (The Los Angeles district attorney’s office denied an interview request for Spear.)

Maybe it was Sophia’s potty accident on the afternoon of May 20, 2014, Spear said, that pushed Carol over the edge. Or maybe it was the fight, recorded in one of the voicemails Carol left for her mom, in which Rudy yelled and cursed at Carol for not cleaning or cooking enough and for not having a job. Carol can be heard meekly begging Rudy to give her $5 for gas. This was a crime of rage and desperation, Spear said, but not delusion.

Carol’s attorney argued the phone call showed a perfect storm of financial stress, sleep deprivation, and lack of support swirling around a mentally ill woman already slipping into the depths of psychosis.

That’s how Carol’s trial went. Every move the prosecutor framed as Carol’s premeditated moral failing, the defense tried to reframe as a clinical symptom of psychosis. Prosecutors said the fact that Carol went back to the kitchen to get another knife during the killings was evidence that she knew what she was doing, and knew it was wrong. Diana Barnes, testifying as an expert witness for the defense, explained this is what psychosis looks like. “In a psychotic episode, these kinds of very methodical robotic, goal-directed behaviors are quite common,” she says.

The DA pointed to statements Carol gave to a detective in the hours after she was arrested. He asked her if she killed her children to “get back at her husband.” She said, “If that’s true, do I get a better deal?” When the detective asked her, “What do you need from us in order to tell us what happened?” Carol responded: “Bedpan.”

“A psychotic mind has a logic all its own,” Barnes says. “What happens in the courtroom is that the state is attempting to use rational, logical thought to explain psychosis, which is illogical and delusional.” Additionally, the symptoms of postpartum psychosis often wax and wane, further undermining defendants’ cases. “If one moment I’m telling you something, but then in the next moment I can’t remember what I just did—that kind of looks like I’m faking it,” Barnes says. “But it’s actually the clinical presentation of postpartum psychosis.”

Carol’s lawyer, deciding not to take his chances with a jury, opted for a bench trial. When delivering his verdict, Judge Ricardo Ocampo said he thought Carol was suffering from a genuine mental health condition. “The court does believe that she needs treatment,” he said. “But the court believes that the treatment will have to be in the state prison.” He sentenced her to three consecutive life sentences without the possibility of parole.

Angela Burling

April Dembosky/KQED

Like Carol Coronado, Angela Burling once stood before a judge after killing her child. There were a lot of similarities between the two women’s cases, except the outcome: One went to prison, the other went home.

In 1983, nine months after Angela gave birth to her second child, Michael, she abruptly stopped breastfeeding him rather than weaning him gradually as doctors now recommend. She started having strange thoughts. “I felt I had a calling to expunge the world of evil,” she says. She began to believe her husband, Jeff, was Jesus. She was the Bride of Christ. And her baby was the devil.

“I felt I needed to drown Michael,” she says. “But then I thought, ‘He’ll come back to life. Jeff will raise him from the dead in three days. Then the world will know: Jeff is Jesus and peace will reign.’ So that’s what I did. I drowned him.”

When the police detectives arrived, her husband pulled them aside. He was a lobbyist and one of his clients was the California Correctional Peace Officers Association. He knew that Angela had postpartum psychosis, because she had experienced it with their first baby and recovered. He asked the police to take his wife to a mental hospital instead of jail, and they did. Her lawyer convinced the DA to charge her with manslaughter instead of murder.

She was still facing serious prison time. Yet the court was ultimately swayed by her own account of what happened: It fit the strict legal test for insanity. She believed her son was the devil and that killing him was the right thing to do. Psychiatrists on both sides of her case agreed she had not been able to tell right from wrong. A judge found her not guilty by reason of insanity and sentenced her to outpatient treatment.

Eventually, Angela recovered. She got a master’s degree in nursing, and after her first marriage frayed from the tension of her son’s death, she remarried. She and her second husband have been together for 25 years.

She takes medication for bipolar disorder; doctors now understand that women with the disorder have a 30 to 40 percent likelihood of experiencing postpartum psychosis. Women who have had postpartum psychosis with one pregnancy have a 55 percent chance of having it again after a subsequent pregnancy. When Angela became pregnant with her third child, she put together a team of psychiatric providers. In their care, she was sure the psychosis would not come back, and if it did, she was certain no harm would come to her baby. “When I found out I was pregnant, I was the happiest woman on earth,” she says. “Because I felt like, I have another chance—to raise another baby. And prove I’m a good mom.”

“I feel like what happened to me is what should happen to other women in my situation,” says Angela, now 64. “I make a case for understanding how it can happen to anybody. I could be your sister, or your daughter, or your wife.”

But Angela had money, her then-husband had connections in law enforcement, and both of them understood postpartum psychosis. Angela believes the way to level the field for all women is to pass laws like Britain’s Infanticide Act. In 1989, state Sen. Robert Presley was so moved by Angela’s story that he recommended California adopt a version of the law. His proposal never went anywhere. “It was a pretty bold resolution,” Angela says. “I don’t know if society was ready for it then.”

Lawmakers in Texas tried to pass a similar law in 2009, but it quickly failed. When women’s health advocates in California broached the topic in 2018, they said lawmakers in Sacramento told them it was the wrong time. That same year, Illinois enacted a law that allows judges to give a woman a shorter sentence if postpartum mental illness played a factor in her baby’s death. Women who are currently in prison in Illinois for infanticide could get a new hearing and a reduced sentence. While it lacks the protections of the British law, it is the first criminal statute in the United States that mentions postpartum psychosis. Women’s health advocates in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New York are hoping to eventually pass similar laws.

If California were to follow suit, KQED’s data analysis shows that more than 40 women currently in prison could have their cases reheard. “We can’t fail these moms twice,” says Joy Burkhard, executive director of 2020 Mom, an advocacy group that is looking for a sponsor for a similar law in California. “They’re failed by the health care system, then again by the legal system.”

When the guards bring Carol out to the visiting room of Central California Women’s Facility in Chowchilla, she still looks as she did in the courtroom photo of her that ran in the papers: straight brown hair, a little greasy, pale skin and no makeup. We get some food from the vending machines. Carol eats all her rice first, then all her beans, then the enchilada in the middle.

Carol has been getting some treatment from prison social workers and psychiatrists, but it’s hard to tell if it’s working. Conversation with her jumps around. She easily veers off onto tangents. Sometimes she says things that don’t make sense. On some topics, she goes into deep detail. Like the last time her family went to the beach. Rudy and Sophie went straight for the ocean, but Yazmine stayed with her. Yazi liked to run her little rake through the sand, look at the lines, then wipe them flat and do it again. Carol says Sophie is just like Rudy, social and playful. Yazi is calm. “Just like me,” she says.

Some of these stories about the girls still come out in the present tense. Throughout her trial, Carol says, she thought her children were still alive. “I literally kept looking for my children, having delusions that they were on the other side of that door, that they were going to walk in at any moment and I would be able to hold them.”

Carol’s parents, David and Julie Piercey, visit their daughter a few times a year. “She had no business going to prison,” her dad says. “She should have been in a hospital, period.” Julie can’t understand “why they didn’t put her in a medical clinic instead of jail.” All they wanted from an insanity defense, was for Carol to go to a place where she could get real treatment. Not a place where other inmates beat her up and call her a baby killer.

They say Carol still says things that don’t make sense. “She tells us, ‘I’m going to be getting out in a couple of weeks or three weeks or a month,’” David Piercey says. “It’s heart wrenching because I know it’s never going to happen.” He can’t bring himself to say anything in response to comments like this. But Julie can’t help but say something. “Okay Carol. I’ll be happy when you get out, sweetheart!” she tells her. “Mama’s waiting for you.”

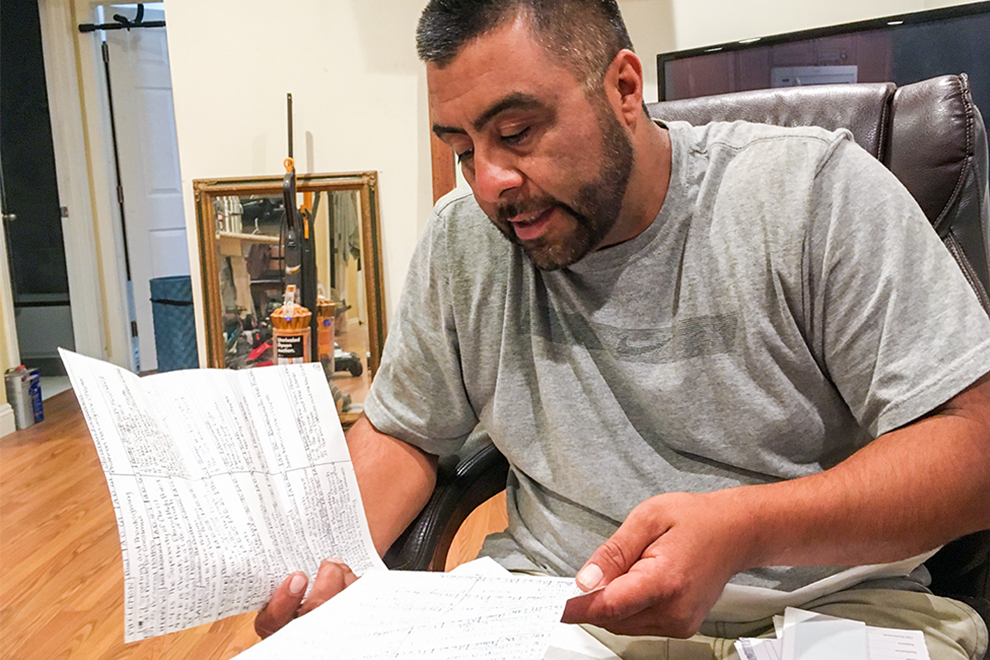

Rudy Coronado with letters Carol sent from prison

April Dembosky/KQED

These conversations are too hard for Rudy. He doesn’t visit Carol in prison anymore. He hasn’t talked to her on the phone in three years. He says, she’s not the same person. He has little stamina for revisiting the past—he still feels guilty that he didn’t know what was happening to Carol. He still thinks about the way he talked to her and if there was something he could have done. He barely goes to work anymore, selling auto parts at the local flea market. “I used to want to get rich, to leave something for my daughters. That was my fire, that was my fuel,” he says. “Now, my fire is gone.”

Yet when women’s health advocates asked him for help, he said yes. He speaks at rallies and forums to raise awareness of maternal mental health and he’s spoken to the state legislature. His testimony helped pass a package of laws in 2018, including the one requiring mandatory screening of new moms for postpartum mental illness. Hospitals in California now have to train staff how to recognize symptoms and the state is has applied for federal money to do more outreach to families.

“I always make it an issue to go and speak to the dad,” Rudy says of his public appearances. “Because no one never talks to the dads.” He tells them: Postpartum mental illness is real. Look for it. Don’t confuse it with regular “baby mama drama.” “This is a famous thing,” Rudy says. “‘Aw, my baby mama’s trippin.’ Now I tell them, ‘Your baby mama is not trippin’. Your baby mama’s going through it.”

The work has helped him to understand what happened to Carol that day, but it hasn’t given him closure. “The way I think about it, like, I blame the disease, not Carol,” he says. “So it’s not that I forgive Carol. I’ve kind of, somehow, not really blamed her.”

Carol still writes to Rudy. He has stacks and stacks of her letters. But he stopped reading those, too. He says she never mentions what happened. She never writes about the girls.

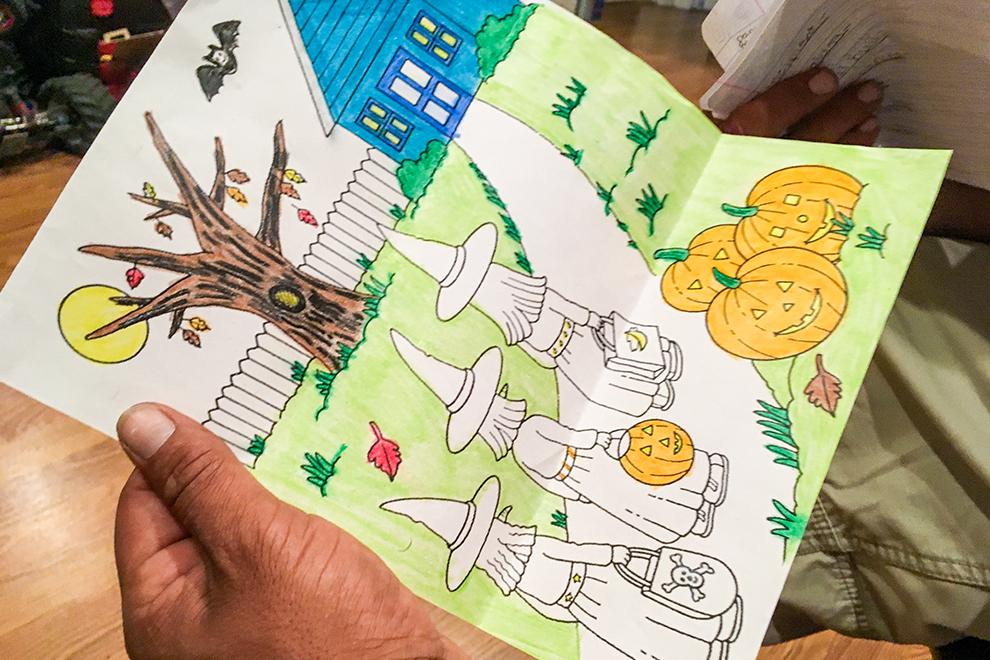

She just draws cryptic images in sets of three: three pumpkins, three stars, three hearts with three letters inside—S, Y, X—the girls’ initials.

Kate Wolffe contributed research for this story.