When the wave of protests swept the United States this spring in the aftermath of the killing of George Floyd, one of the first monuments to come down was across from a Bruegger’s at the baggage claim at Dallas’ Love Field. It was a 12-foot bronze of a man with a pistol holstered on his hip and a cowboy hat on his head, lowering his left hand to appeal for calm. His name was E.J. Banks, and he was a Texas Ranger.

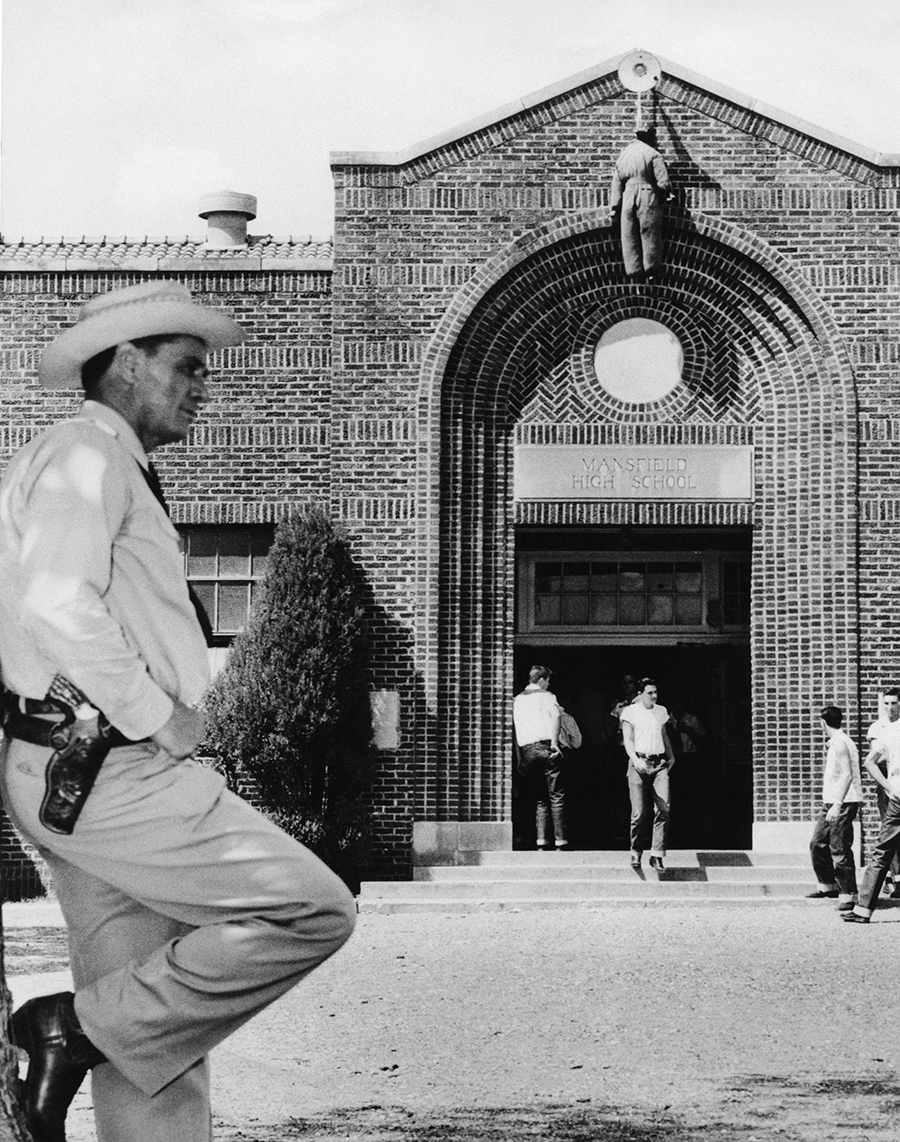

What precipitated the removal, in early June, was an excerpt, in D Magazine, from a new history of the Rangers called Cult of Glory, by former Dallas Morning News reporter Doug Swanson. In it, Swanson detailed Banks’ story: He was dispatched to North Texas in 1956 to prevent Black students from desegregating a high school. A photographer captured Banks, leaning against a tree, as an effigy of a Black student hanged above the school’s entrance. The statue, titled “One Riot, One Ranger,” was commissioned three years later.

United Press Photo/AFP/Getty

Domingo Garcia, president of the League of United Latin American Citizens, the nation’s oldest Hispanic civil rights organization, told me he was glad to see the Ranger come down—something he had first called for as a Dallas City Council member in 1992. But he and LULAC believed a more substantial change was in order. “The Rangers need to be disbanded,” he said. “They’re a national disgrace.”

It is not the first time the 197-year-old law enforcement division has faced a reckoning. Today the idea of abolishing police departments and other law enforcement agencies such as ICE sounds new and radical to the uninitiated, but in Texas, in 1919, the future of the Rangers was uncertain. Over the previous decade, the Rangers, who had evolved from a frontier guard into a state security force controlled by the governor, had swelled in response to fears of violence on the southern border. In reality, the Rangers instigated a reign of terror in which between 300 and several thousand Mexican nationals and Mexican Americans were killed.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

For almost two weeks in Austin, a single, courageous lawmaker, José Tomás Canales, put the Rangers on trial. A century later, the transcripts are essential for understanding our current moment—a remarkable document on race and the police, and the mechanisms of state violence and bureaucratic whitewashing.

The Rangers have been portrayed in popular culture as icons of law and order. To Garcia and others, the statue symbolized the myth underpinning their entire history—a lie laid bare by Canales a century ago.

J.T. Canales was a political insider who could never shake the prejudices that classified him as an outsider. Born on a ranch outside Corpus Christi, he studied law at the University of Michigan before returning to a South Texas that was rapidly changing. In the first decades of the 20th century, railroads and irrigation brought Anglos to the Rio Grande Valley in droves. The newcomers pushed people of Mexican descent from their land and took control of local levers of power. But the bilingual Canales—wealthy, charming, and well-connected—found unusual success in the local politics. When he was elected as a state representative in 1904, he was the only Mexican American in the chamber. When the legislature convened in January 1919 to consider the future of the state’s oldest law enforcement agency, he still was.

The Ranger investigation was overdue. As Swanson lays out in Cult of Glory, the Rangers had served since their creation as enforcers of white power. When a president of the Republic of Texas called for an “exterminating war” against American Indians, the Rangers were his muscle. After statehood, Rangers hunted fugitive slaves and committed atrocities against civilians during the Mexican–American War. In the 1910s, ostensibly for protection during the Mexican Revolution and World War I, the state doubled the size of the force and deputized a thousand more men. Governors appointed volunteer “special” Rangers—often as personal or political favors—who were still empowered to shoot to kill. Residents had a term for neighbors who vanished after encounters with Rangers: They “evaporated.”

Canales had raised his concerns about the force before, but the promised reforms never came. In early 1918, a company of Rangers executed 15 men in the West Texas village of Porvenir in retaliation for a raid from across the border. The unit responsible was disbanded, but most of its members remained on the force. Allegations of abuse continued. After Canales complained to one of the leaders of the force, another Ranger confronted him on the street. The Ranger—one of those hard men the force hangs its hat on, who later bragged he’d been shot 23 times—told Canales that if he didn’t back off, he was “going to get hurt.”

The stakes were set for a battle. Canales wrote a bill that would shrink the Rangers to prewar levels. Most importantly, they would be bonded so that victims could have legal recourse—similar to the idea of ending qualified immunity. His bill gained steam in Austin. But then the Rangers fired back. Accusing Canales of trying to abolish the Rangers, they demanded a public investigation. Their future, and his, would be settled in the hearing room.

A special committee of seven lawmakers—all Anglos, none from the border—was hastily assembled. The hearings started at the end of January. Canales had not expected to be thrust into the role of inquisitor. He struggled to line up witnesses willing to testify on the record. And he was working in a state of emotional distress, believing he was going to be murdered. “I do not expect to live six months…if this bill is killed,” he told colleagues. At one point, he took refuge in a local jail. The Rangers taunted him by offering to provide security.

Which makes it all the more remarkable that the hearings uncovered as much as they did. Day after day, Canales brought to light new abuses. Toribio Rodriguez was taken from his home and shot in the back by a deputy sheriff working with a Ranger captain, then left in a jail cell to die. A Ranger killed Lisandro Muñoz after mistaking him for another man. Florencio García was apprehended by three Rangers; his bones were later found in a pasture. A judge recalled discovering the decomposing bodies of 11 men off a country road. Canales displayed a photograph for sale around Brownsville: It showed three men on horseback—one a Ranger captain—mugging for the camera above four bound corpses.

And what kind of men were joining the Ranger force, anyway? One of them was hired after twice being convicted of murder (both convictions were overturned). Another received his badge after handing over a prisoner named Rodolpho Muñoz to a lynch mob. One night, while the hearings were ongoing, two Rangers engaged in a drunken shootout near Austin. Internal documents showed how the bureaucracy provided cover for the officers it was supposed to investigate.

The arguments that bad cops make to excuse abuses have not changed much over the last century. The Ranger who shot Lisandro Muñoz said the victim had grabbed his Winchester—the officer feared for his life. Others might have lived had they not tried to run. Then, as now, the evidence of guilt was never so clear as when the autopsy necessitated finding it. Rangers claimed to have found stolen property at Porvenir. Florencio García was a “notorious cow thief”—he was no angel.

Bettmann/Getty

The Rangers tried to hold onto their power by demanding law-abiding Anglos pick a side. Their accusers were enabling banditry and a culture of lawlessness; the Rangers were for law and order, even if you blanched at their tactics. They continued to falsely accuse Canales of wanting to abolish the force. The Rangers were a “living monument”—Texans must band together against those who would tear it down. Claude B. Hudspeth, a Texas congressman and rancher, testified that “good citizens” feared that their country would be uninhabitable without Ranger brutality. “You have got to kill those Mexicans when you find them,” he said, “or they will kill you.” He would go on, five years later, to help found the US Border Patrol.

As the investigation progressed, it at times seemed like Canales was the one on trial. Opponents of his bill invoked the Alamo and argued that reform would serve only “the interest of Mexicans.” The attorney for the Rangers, Robert E. Lee Knight, accused Canales of failing to condemn bandit violence with the same force he decried Ranger violence—a cousin to that canard about “Black-on-Black crime”—and put the legislator on the stand.

“Now, Mr. Canales, you are by blood a Mexican, are you not?” Knight asked.

“I am not a Mexican. I am an American citizen,” Canales responded.

Knight asked Canales to name “a single white citizen” that he’d “assisted out of trouble.” Canales had married the Anglo niece of a Confederate general, joined the Elks, and earned plaudits from a future vice president. He’d formed his own unit of scouts to surveil the bandits and crossed the Rio Grande to negotiate an end to the raids. But none of that mattered once he crossed the police.

The committee members defended their colleague against insinuations of disloyalty, but their final report amounted to a spirited defense of the Rangers and acquitted their leadership of mismanagement. Canales’ bill was scuttled. A more modest reform bill succeeded in capping the size of the force, and the Rangers’ adjutant general, reading the winds, discharged nearly 800 Rangers on his own. But the new version made no mention of bonding officers. It would be up to the police to police themselves.

“I refuse to recognize my child,” Canales said of the law. He retired from politics at 43.

The hearings had gripped the state for weeks. And then, almost as soon as they were over, they were buried. “The state was supposed to publish the transcripts of the investigation,” says Monica Muñoz Martinez, an associate professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin, whose 2018 book, The Injustice Never Leaves You, examined the legacy of anti-Mexican violence in Texas. But the legislature reversed course. Instead, the original bound volumes languished in an Austin archive.

In the decades that followed, the force continued to act as enforcers for Anglo dominance, infiltrating NAACP chapters, blocking desegregation efforts, and cracking down on striking farmworkers. In a pattern that repeats itself today, officers fired for abuses often signed on with other law enforcement agencies. “Some of them receive federal appointments as immigration and customs officials,” Martinez says. “Some of them go on to be Border Patrol agents.” The captain responsible for the Porvenir massacre was eventually rehired. In his book, Swanson relays the story of a Ranger who abandoned a Black prisoner to a white mob. The Ranger was Frank Hamer—the same officer who had threatened Canales 11 years earlier.

Rather than reform, the Rangers turned to propaganda. Those years saw the rise of what Swanson calls “the fable factory.” Rangers wrote books and consulted in Hollywood. State officials funded museums and monuments. In some cases the agency worked directly with producers to promote the heroic Ranger image—all part of a deliberate attempt at mythmaking that shielded Rangers from scrutiny while writing their victims out of official history.

“Those of us who were baby boomers, that was sort of how the Ranger image gets baked into our minds,” Swanson says. “My first notion of a Texas Ranger was when I saw one on TV.”

The perception was Chuck Norris. The reality was Blood Meridian. (Seriously. The Cormac McCarthy novel features a sadistic gunslinger who harvests Indian scalps for bounties—he was inspired by a real-life Ranger.) These media portrayals have reinforced the idea Knight had pushed at the hearings—that Rangers were a check against lawlessness, rather than perpetrators of it. Hamer, valorized for taking down Bonnie and Clyde, killed at least 53 people. He’s in the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame; just last year Kevin Costner played him in a movie. There’s something judolike about the way Rangers have turned criticism into validation. In 1970, half a century after the Canales hearings, the Texas Advisory Committee of the US Commission on Civil Rights concluded its own investigation into racist practices, including abuses of Mexican American farmworkers by the Rangers in South Texas. The commissioners called for the force to be abolished. Once again, the result was Anglo retrenchment. Baseball’s Washington Senators relocated to the state the next year. With a new home came a new name: the Texas Rangers.

In defeating Canales, the Rangers won a fight over memory that shaped the century to come. It’s not that the communities traumatized by Ranger violence stayed quiet. The Rangers baseball team was met with protests from LULAC when it debuted, and a gubernatorial candidate in 1972 with La Raza Unida Party campaigned on eliminating the force. But the Ranger mystique hummed along. Now the records are no longer hidden, and over the last two decades, Canales’ work has finally had something of a second life, as activists and researchers chipped away at the Ranger facade and forced a conversation about one of the most exalted symbols of the American West. In 2013, fed up with the way the state had erased the people it had terrorized, Martinez and a few other historians formed a group called “Refusing to Forget,” devoted to commemorating the legacy of anti-Mexican violence—much of it perpetrated by Rangers. The group erected historical markers near lynching sites and displayed the original Canales transcripts at the Bullock Texas State History Museum.

LULAC is itself an indirect legacy of the hearings—the group was formed in 1929 in response to the systemic racism faced by Mexicans in places like South Texas; Canales was a co-founder and early president. It speaks to the depth of the whitewashing that Garcia, whose family hails from Porvenir, told me he first heard about the hearings last year, at a screening of a new PBS documentary about the massacre, when he also met Canales’ great-nephew.

“You read about The Lone Ranger and Walker, Texas Ranger but you don’t read about the reality,” Garcia said. “These were cold-blooded killers.”

This year’s protests have linked contemporary acts of state violence and the iconography and institutions that venerate it over time. Unlike Confederates or Columbus, the Rangers are still around and profiting from their past—they’re a “living monument,” as that booster once said. That inherited gravitas is essential to their work. These days, Garcia points out, the Rangers are the ones brought in to investigate when a local law enforcement officer kills a civilian, or when a Texan dies in custody (such as the 2015 death of Sandra Bland). “The Texas Rangers come in and they whitewash the killing and always absolve the local police officer,” he says. It’s the same complaint Canales made in 1919: No one’s policing the police.

After the Love Field statue came down in June, other symbols appeared to be on the chopping block. Later that month, officials at Texas A&M announced they were reexamining the university’s statue of Lawrence Sullivan Ross, a celebrated Ranger, Confederate general, and governor—an about-face from the defiance such protests elicited from school officials just a few years ago. MLB’s Rangers may not be in danger, but San Antonio College, after pressure from a student group called Somos La Gente, announced in July that it would retire its Rangers mascot.

The school solicited public comments before it made the change official. One respondent named relatives lynched by Rangers in South Texas. Another was the descendant of men killed at Porvenir. Others cited Refusing to Forget. The movement was rooted in history. Last year members of Somos La Gente attended a conference commemorating the centennial of the Canales investigation, where high schoolers performed scenes from the transcripts, and Nati Román, the group’s president, read a poem she’d written. As Somos La Gente stepped up its campaign to rename the mascot this spring (before campus shut down), members handed out zines detailing “the violent history of our mascot.” One spread caught my eye—it was the photo Canales introduced at the 1919 hearing. There were the three men on horseback, the ropes pulled taut around the bodies of their quarry. And this time the victims were named: Jesús Garcia; Mauricio Garcia; Amado Muñoz and his brother. “Do these Rangers represent us?” it asked. The work of the Canales hearings never ended. It’s a living monument, too.

Read the full transcripts from the special committee’s investigation: Volume 1 | Volume 2 | Volume 3