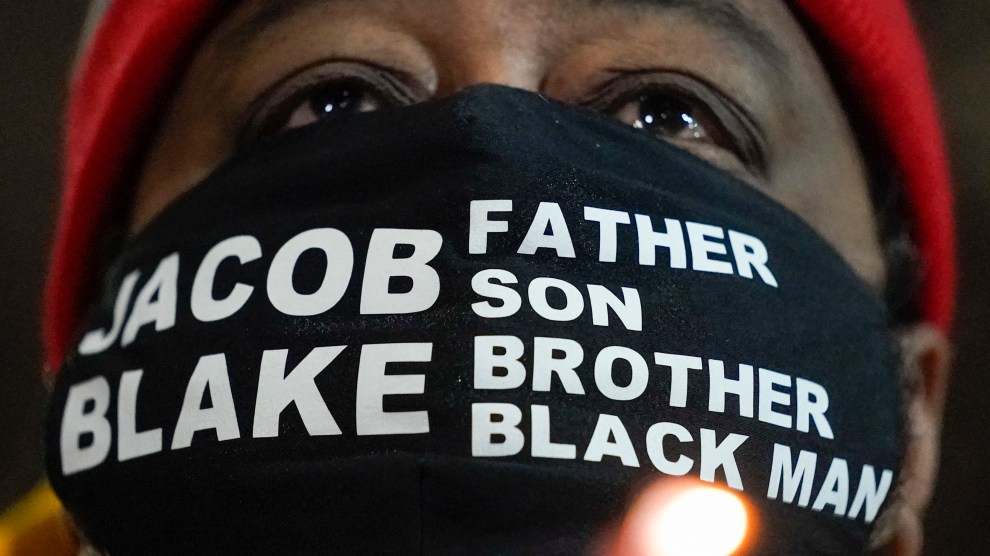

Jacob Blake Sr., father of Jacob Blake, holds a candle at a rally Monday in Kenosha.Morry Gash/AP

Jacob Blake, paralyzed and still suffering from injuries, got a phone call on Tuesday afternoon from Kenosha District Attorney Michael Graveley with some news: There would be no charges filed against the police officer who shot Blake seven times in August, sparking massive protests in the city.

“Based on the facts and the law, I have decided not to issue criminal charges against Officer Sheskey, Officer Meronek, or Officer Arenas. This decision was by no means easy,” Graveley wrote in a report published later that day. In a press conference, he described the shooting as a “tragedy.”

The video of the shooting has been viewed by millions of people, and is difficult to watch: Blake, who is Black, walks toward the driver’s side of a parked car in a residential Kenosha neighborhood, with his children in the back seat. A white officer, Rusten Sheskey, follows behind him with a gun drawn. As Blake approaches the door, Sheskey grabs him by the shirt and then fires his weapon.

It can be hard to imagine how Sheskey’s actions wouldn’t warrant criminal charges, even considering the blatant racism of our criminal justice system. But District Attorney Graveley, in a roughly two-hour press conference, argued that pressing charges would be unethical because, given the state’s law about when officers can use force, there was no way he could win at court.

Even after atrocious policing, even after a man is paralyzed, use-of-force laws around the country often make it very, very difficult to punish cops. In Wisconsin and most states, police can legally fire their weapons against someone if they have “reasonable” fear the person will otherwise gravely harm them or someone in the vicinity. And here’s the kicker: The law usually says police officers get to define what’s reasonable.

At the press conference, Graveley explained why police could successfully argue that Sheskey’s decision to shoot was reasonable under the circumstances, using evidence not visible in the viral video most of the country watched.

According to Graveley, the police had reason to be nervous off the bat: Three officers were called to the scene by Laquisha Booker, the mother of Blake’s children, who told a 911 dispatcher that Blake had grabbed the keys to her rental car and was trying to take their kids away from her, according to a recording of the call played at the press conference. The officers knew that Blake had a felony warrant for alleged domestic abuse and sexual assault. When they arrived at the scene and tried to arrest him, a physical confrontation ensued—Blake says the officers punched him and dragged him to the ground, and the officers say he resisted their orders. At one point during the struggle, Blake was on top of Sheskey on the ground, according to a second video. Officers tried to stun him with a taser, but he tore the prongs out.

Blake admitted to investigators later that he was holding a knife in his hand after he stood up and began walking to the car. Sheskey says he followed Blake and then grabbed his tank top because he feared Blake would take the car with the children inside. (Booker had yelled that the children were hers.) According to a statement Sheskey gave later, he worried that if Blake drove away, it could result in a high-speed chase that could harm the kids, or they might be taken hostage. An independent police expert, former Madison Police Chief Noble Wray, concluded it was reasonable for Sheskey to grab Blake, according to the district attorney.

In the video footage, it looks like Sheskey then shot Blake seven times in the back. But according to the district attorney, two police officers and citizen witnesses told investigators that before the shooting began, Blake started turning toward Sheskey and made a motion with his knife hand; this allegation couldn’t be confirmed in the video because the camera view was obstructed by the car door and another officer. A medical examiner later concluded that Blake was shot four times in the back but also three times on his left side, adding some corroboration to the allegation that he turned.

Wray, the independent police expert, concluded it was reasonable for Sheskey to fear that Blake was trying to stab him at that time. Blake denies this allegation and says he was simply trying to put the knife back into the car. “They didn’t have to shoot me like that,” he said in a statement later, published in the district attorney’s report. “I was just trying to leave and he had options to shoot my tires and even punch me, tase me again, hit me with the night stick.”

If you asked many people on the street, they’d probably say it’s unreasonable for a cop to follow behind a man who is walking away, grab him by the shirt, and proceed to fire multiple shots into him at close range while his children watch from the back seat. But our laws are set up so that it doesn’t really matter what most people think: It matters what a police officer decides is a reasonable fear. And in a racist society where Black people are too often viewed as threats, police will almost always be able to come up with some justification for why they were afraid and believed they had to shoot.

Prosecuting cases like this will require states to change their use-of-force laws, so that officers don’t have so much power to define what’s reasonable. Until that happens, law enforcement will regularly get away with shooting people, including those sleeping in a car or at home on a couch, when it might have been possible to deescalate the situation instead. Officers continue to get away with violence because it’s not very hard to come up with a reason why they thought someone would harm them, especially when the law doesn’t require them to prove that they were correct or that the person was actually a threat. “Without any new rules from the legislature, we’re going to have this problem again and again,” says Farhang Heydari executive director of the Policing Project at the NYU School of Law. “We saw it in Breonna Taylor’s case, Eric Garner’s case, with Tamir Rice. It will happen over and over again until legislators step up and enact clear rules around force.”

It’s possible to change these use-of-force laws, which often differ from state to state and even city to city. California recently amended its statute so that an officer can only legally shoot if it’s “necessary,” rather than “reasonable,” to protect against an imminent threat of death or serious injury. But even there, it’s hard to predict whether the statute will bring justice after future police shootings, because California lawmakers didn’t define what “necessary” means in the law, again potentially leaving some room for discretion among police officers.

More than half of states considered legislation last year dealing at least in some way with police use of force, and at least several focused on deadly force. But many of the bills didn’t go as far as some criminal justice reform activists would hope. Delaware’s attorney general has pushed to reform her state’s law, but her proposed changes wouldn’t even go as far as California’s did: Delaware’s statute currently allows deadly force if an officer believes he or she is in danger. The attorney general wants to reform the law merely to specify that it must be a “reasonable” belief—which brings us back to the problem in Wisconsin and many other states.

The Policing Project’s Heydari recommends that new laws require officers to take deescalative steps, and to only use force as a last resort, limiting the types of response depending on the situation. Fair and Just Prosecution, an advocacy group that works with district attorneys, recommends a ban on deadly force against suspects who are fleeing.

Under the Biden administration, the federal government could step in to encourage these changes. The Justice Department, which may soon be led by US Circuit Judge Merrick Garland, Joe Biden’s nominee for attorney general, could set a national guidance on when it’s acceptable for officers to use lethal force. The agency or Congress could also require states to follow this guidance in order to receive federal funding for training or other programs. Biden’s pick to head the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, Kristen Clarke of the National Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, formerly prosecuted police brutality at the department. She supports efforts to scale back law enforcement and invest more in social services, and has encouraged the federal government to stop funding agencies with a long history of violence and racism.

In terms of Blake’s case, federal prosecutors at the Justice Department and a US attorney’s office are now conducting a civil rights investigation and could later decide to bring federal charges. The Justice Department could also launch an investigation into the Kenosha Police Department and push for a consent decree that would require reforms.

“Now our battle must go in front of the Congress, it must go in front of the Senate,” Blake’s father, Jacob Blake Sr., told reporters Tuesday after the district attorney’s decision not to file charges locally. One of Blake’s attorneys, Benjamin Crump, said they would press forward with a civil rights lawsuit. “It is now our duty to broaden the fight for justice on behalf of Jacob and the countless other Black men and women who are victims of racial injustice and police brutality in this country,” he said in a statement.

“We’re going to talk with the Speaker of the House, Speaker of the Senate,” Blake Sr. added. “We’re going to change some laws. Some laws have to be reckoned.”