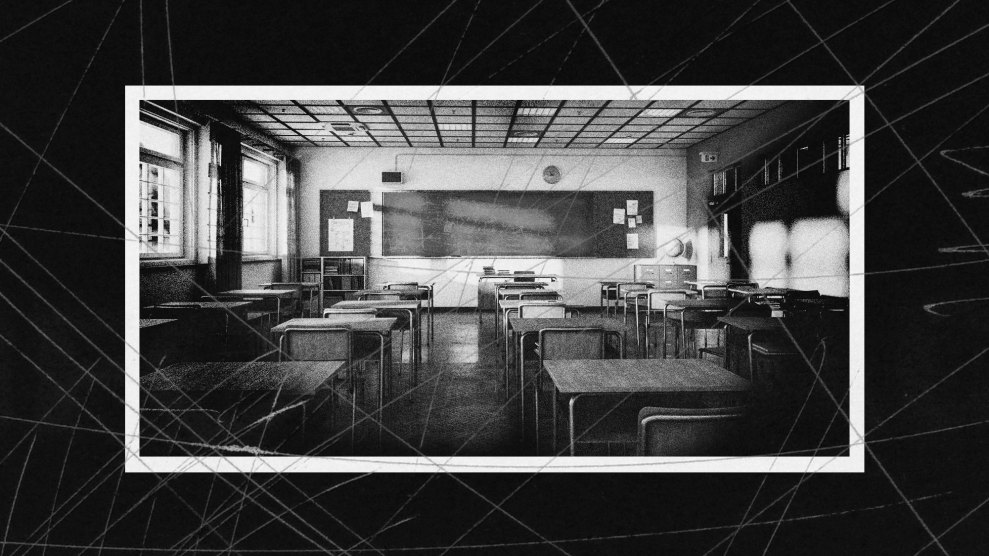

A police officer directs traffic at Richneck Elementary School, where a 6-year-old boy shot his teacher in January.John C. Clark/AP

A decade ago, with school shootings on the rise across the country, Virginia passed a law requiring all K-12 districts to adopt a violence-prevention method called threat assessment. The method—which relies on trained teams of administrators, counselors, police officers, and others to evaluate and manage alarming behavior—is designed to help avert tragedies like the one last month at Richneck Elementary in Newport News, where a 6-year-old seriously wounded his teacher.

But after the law was enacted in 2013, the Newport News district failed for years to use—or even establish—the required threat assessment procedures, according to interviews with three psychologists who previously worked for the district.

The psychologists, who asked not to be identified, worked for Newport News Public Schools over the past decade and left for jobs elsewhere prior to the current school year. Collectively, they have broad experience with how the school system handled behavioral issues and violence risk, and since the shooting in early January they have been in touch with colleagues currently working in the district.

The three psychologists described a chronic lack of violence-prevention training and said the district never set up the necessary threat assessment teams. Such teams look into cases of concern and draw on their range of expertise to gauge the level of danger. They make a plan to intervene with a troubled or disruptive student as constructively as possible, seeking to work with parents and using individual education plans, counseling, mentoring, and other tools. The team is then supposed to track the cases and follow up as needed.

Essentially none of that was happening in the Newport News schools, the sources said.

“There were no clear and consistent procedures and almost no threat assessments occurred,” one of the school psychologists told me. “There was also no tracking system for threats or their outcomes. The last time I had done any formal training was in 2014.” This psychologist worked in nearly a dozen of the district’s 41 schools over the years. “I usually handled cases on my own as there was no designated threat assessment team at any of my schools,” she said, adding that colleagues who worked in other buildings had similar experiences.

“It made me very uncomfortable,” said another school psychologist, who asked administrators repeatedly for clarity on doing the work. “No one could direct me to a division-wide procedure.” Eventually, during the 2019-20 school year, a supervisor told her to evaluate threats essentially on her own, which is counter to the method’s core principle of collaboration and guidelines published by Virginia’s overseeing agencies. The supervisor told this psychologist and other staff to make their evaluations using limited case forms that were to be filled out by assistant principals, who are in charge of disciplinary issues in their buildings. But most of those administrators had no threat assessment training and they often declined to engage in the process, the psychologist found. “In the schools I worked in, the assistant principals looked at the form and said, ‘I’ve never seen this in my life.’”

A third school psychologist who worked in the district for a shorter period until recently confirmed there were no official teams or procedures. She told me that when a concerning situation came up in one of the several schools she covered, “the system felt totally unprepared.”

After the 6-year-old fired a single bullet from a Taurus 9mm pistol on January 6, the 25-year-old teacher he shot, Abigail Zwerner, quickly ushered her other students out of the first-grade classroom. Another staff member restrained the boy until police arrived. Zwerner soon collapsed and was rushed to a local hospital where she went on to recover from a wound to her hand and chest. The boy was placed in emergency state custody and hospitalized for evaluation.

Details disclosed by local authorities, news reporters, and a lawyer representing Zwerner soon brought into view a devastating picture of a tragedy that experts say could have been prevented. The gun had been purchased by the child’s mother and brought by him from home; teachers had warned school administrators that the boy had a weapon on campus, prompting an unsuccessful search of his backpack; and school staff, including Zwerner herself, had long sounded alarms about disruptive behavior and violent threats from the child.

In late January, Michelle Price, a spokesperson for Newport News schools, told me the district “is in compliance” with Virginia’s threat assessment law. Citing federal privacy protections for students, she declined then to comment about the shooting, including whether the 6-year-old had been the subject of a threat assessment case. She did not respond to detailed follow-up questions about use of threat assessment in the district.

All three former school psychologists emphasized in separate interviews that many “wonderful” and “diligent” people work in Newport News schools and care deeply about the children. The three psychologists’ combined experience in the district spans a decade; they left their posts on amicable terms for various life or career reasons. Each indicated a desire to speak out in hopes that it might help lead to improving the system.

“We in education can’t prevent kids’ mental health emergencies or access to guns, but threat assessment is something tangible that we can do, and it’s so frustrating that it wasn’t done,” the first school psychologist remarked. “This type of situation doesn’t come out of nowhere—there were so many warning signs.”

Constructive interventions at the hands of experienced threat assessment teams have produced some remarkable results in various parts of the country. As I document in Trigger Points, my recent book about preventing mass shootings, the work has saved lives. It has also helped diminish school expulsions and contact with the juvenile justice system, which disproportionately harms students of color. Along with Oregon and Colorado, Virginia has been at the forefront of the emerging field and was the first among at least a dozen states that now require threat assessment in schools. (Virginia’s role is no coincidence: It has been an epicenter both for notorious gun rampages and the field’s evolving research, as I chronicle in my book.)

Yet, effective behavioral threat assessment requires the commitment of leadership and resources, and that can be particularly challenging in communities with significant levels of poverty and trauma. “Districts like Newport News are already starting from behind due to all the challenges that the students and families come with,” said one of the psychologists. Student discipline and attendance problems put pressure on school accreditation requirements, which in turn can disincentivize focus on disruptive behavior—a dynamic raised during a contentious Newport News school board meeting in January.

After the school board fired superintendent George Parker, they made Michele Mitchell the interim superintendent as of Feb. 1. Mitchell also serves as the district’s executive director of student advancement—a position whose responsibilities, according to the former school psychologists, would have included overseeing the threat assessment programs that should have been in place. (Mitchell did not reply to a detailed request for comment about threat assessment and her role.)

The district may have been lucky in some past cases. One of the school psychologists described a high school student she evaluated several years ago: The student had been suspended after threatening to shoot up his school, faced criminal charges, and upon return required a special education evaluation. She soon sat down with him.

According to her account and case notes she shared with me, the student (whose identity she redacted) had severe problems. He had nearly flunked out of middle school and felt no motivation to improve. He spoke of being bullied and feeling extremely isolated. Friends “always leave or betray me,” he said. He was fixated on violent video games and said he “loved explosions and gunfire.” He described having multiple clinical afflictions, including anxiety and depression. A few weeks earlier, he had drunk some bleach impulsively, landing him in an ambulance to the hospital.

“What will help?” she asked him.

“I don’t know, we tried everything,” he replied. He also told her: “I’m going to do something after high school that’s a secret and I’m not going to tell anyone.”

With no threat assessment team to consult with, the psychologist dusted off a manual from a training earlier in her career. “I did my best to do the entire thing myself,” she said, even though that went against the method’s core collaborative approach.

The student’s mother was unresponsive and had decided by then to homeschool him, and the psychologist feared he might still return to the school to commit violence. She spoke with the student’s probation officer and a school resource officer, who were each reluctant to share any information with her about the case because of legal privacy concerns—a common misconception about handling threat cases that has marked many tragic school shootings.

“It was still clear enough to me that they thought he had access to weapons at home,” she said. She sent the probation officer her evaluation report. He thanked her, and that was the last she heard of the case.

“I was really worried about that kid,” the psychologist said. “He was the kid who scared me the most in my career.”

Tough questions also persist about the family of the 6-year-old shooter, who authorities have not identified publicly. A statement the family issued through an attorney in mid-January seemed to suggest that the child’s “acute disability” was to blame for the shocking violence. But such an explanation would warrant sharp scrutiny, as I wrote recently, because it is stigmatizing and leans into the major myth that mental illness is the sole or fundamental cause of school and mass shootings, which is in fact rarely the case.

Two leading threat assessment experts I spoke with noted that it isn’t possible to know the meaning of “acute disability” in this case, let alone to evaluate the possible relevance, without learning more: Did he have a clinical diagnosis? If so, was it made when he was evaluated after the shooting, or prior to the shooting? What comorbid conditions, other behaviors, or exacerbating circumstances were there? And so on.

According to one of the school psychologists, who is knowledgeable about the handling of the 6-year-old boy at Richneck Elementary, “he was on everybody’s radar” since last fall. Despite the fact that there were no threat assessment procedures to follow, some school staff were in contact with the family, who indicated they had a plan for the boy to be evaluated. The school staff “were waiting for that to happen,” this psychologist said, but she was unclear on whether it did.

Questions about how the boy got the gun and knew how to commit a shooting are even more fraught. The family said in its statement: “The firearm our son accessed was secured.” An attorney for the boy’s mother told the Virginia Pilot in late January that she had a trigger lock on the gun. She stored it “out of reach of the child,” the attorney said, “on the top shelf of a closet.” How the boy obtained the weapon or overcame the trigger lock was a mystery, according to the attorney. “I don’t think any of us know,” he said, adding that the mother “has no idea how the child got the gun.”

The two threat assessment experts I spoke with both highlighted a fundamental point belied by the lacking context on the gun.

“The 6-year-old learned his behavior somewhere,” as one of them put it to me.

From school safety to Virginia’s lack of safe storage laws for guns, the high-profile case continues to underscore daunting questions about culpability and how to make progress. In the aftermath of the Richneck shooting, the local school board quickly announced plans to install a bevy of new metal detectors throughout the district, and Gov. Glenn Youngkin called for greater police presence in Virginia schools. While such “target hardening” and other reactive security measures have been the heavy emphasis in America ever since the Columbine massacre in 1999, school shootings have nonetheless risen. Even in a state that has mandated threat assessment for a decade, the method’s use and potential still draws scant attention from elected officials, even after fresh tragedy.

“It’s just awful that the community is going through this, because this was so foreseeable,” said one of the school psychologists. “I just want change for the kids.”