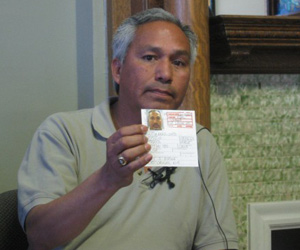

Photo courtesy of <a href="http://latinousa.kut.org/2009/02/12/fleeing-violence-mexican-journalist-seeks-asylum-in-us/">Latino USA</a>

To those of you that have not already read “We Bring Fear,” Chuck Bowden’s amazing piece on the plight of Mexican journalist Emilio Gutiérrez Soto, well, get on it. For everyone else, I thought I’d share with you how Immigration and Customs Enforcement used a ridiculous legal argument to keep Emilio behind bars and separated from his son for seven months.

Mother Jones obtained a copy of one of the rejection letters sent to Emilio and his lawyer, Carlos Spector, after they requested Emilio’s parole. (See annotated version below). In it, Robert Jolicoeur, Field Office Director at the El Paso center where Emilio was detained, claims that Emilio failed to meet 4 of the 5 criteria required for asylum applicants to receive parole. But the grounds are bogus, as you’ll notice—and this is an example of what Carlos Spector referred to as the “Guantanimization of the refugee process.” (It’s a dirty little secret that during the Bush years asylum applicants from Mexico were held indefinitely to discourage them from pursuing their asylum claims.) The nonprofit Human Rights First released a great report on refugee Guantanimization in April: “U.S. Detention of Asylum Seeks: Seeking Protection, Finding Prison.”

See Emilio’s actual rejection letter and read a debunking of each provision after the break.

To set the record straight, let’s go through and break down the injustice in each of these boxes.

1. You have not sufficiently established your identity.

Um, Emilio showed up at the border with his notarized birth certificate, driver’s license, voter ID card, press pass, Lion’s Club membership card, multiple letters addressed to him from the Mexican National Commission of Human rights, and son. But yeah, he could’ve been faking right? I mean, he doesn’t even speak English!

2. You have not established that you will appear as required for immigration hearings or other matters.

You know what Emilio could have done? He could have entered the country as a tourist, or as a journalist reporting something, or, even, illegally. At that point he could have saved his life and that of his son and figured out where to go from there. But he didn’t do this. Emilio arrived at the border and immediately declared his intention to pursue political asylum through the proper avenues. He provided the names and addresses of friends he would be staying with in El Paso, and hired a well-known immigration lawyer. Does this sound like someone about to disappear underground?

3. You have failed to establish that your parole would not pose a danger to the community.

Perhaps the most insulting of the claims. Recall that Emilio, a journalist, was fleeing the Mexican army because he published accounts of their abuses against civilians in northern Chihuahua. Additionally, he presented letters from the mayor of Ascension, the director of El Diario newspaper (his boss), and the president of the local Lions Club, vouching for his character and long time employment as a reporter in the region.

4. You have not established that you are described in one or more of the 5 categories of 8 C.F.R. section 212.5 (b).

Ironically, this is the one category where the ICE gave Emilio the thumbs up; it’s also the category that Emilio needs to prove in court if he is to receive asylum. And it’s by far the hardest of the parole provisions to prove. The five categories they’re referring to are the five grounds upon which asylum can be granted: 1) Race, 2) Religion, 3) Nationality, 4) Membership in a particular social group, and 5) Political opinion. Emilio’s strongest claim is that his political opinion has endangered him.

5. You have failed to demonstrate that your parole would be justified for urgent humanitarian reasons or would yield a significant public benefit.

At the personal humanitarian level, Emilio is a single father who has been separated from his 15-year-old son. His son was detained for 2 months before being released to friends, but spoke no English and was very much alone and helpless. Meanwhile, Emilio was detained like a common criminal and forced to work at the prison for 1 dollar per day. In the bigger picture, imprisoning a journalist for reporting the abuses of the military is against everything we supposedly stand for. When Seymour Hersh investigated abuses we praised him; when Emilio Gutiérrez Soto did it we imprisoned him. Emilio has a long record of investigative journalism, including a series of stories that eventually prevented a toxic waste plant for being built in his hometown. If you believe that smart, fearless journalism can do good in the world, then releasing Emilio to continue his life’s work does, indeed, yield a significant public benefit.