<a href="http://www.blingcheese.com/image/code/33/prison+bars.htm">blingcheese.com</a>

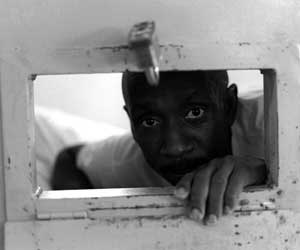

As heatwaves swept the Northeast earlier this month, 30 inmates in solitary confinement at New Hampshire State Prison went on hunger strike to protest stifling temperatures inside the prison’s Special Housing Unit. According to the Concord Monitor, “Inmates in SHU cannot open windows and must remain in their cells, usually alone, for 23 hours a day. Unlike inmates in the prison’s general population, they also can’t go outside.” One visitor to the prison said that inmates were “sitting in pure sweat,” and had begun flooding their cells with a few inches of water in order to cool off.

A Department of Corrections spokesperson told the Monitor that inmates were refusing to eat until fans were installed, whether in cells or in nearby hallways. According to the paper, fans had recently been removed due to “safety concerns”: Many prisoners, the DOC claimed, “were tearing them apart and fashioning them into weapons.” Yet the prison also refused to place fans in the unit’s hallways, where they might have benefitted both staff and inmates.

When purposefully used against prisoners in the so-called War on Terror, “extreme temperatures”—including high temperatures reaching 100 degrees—have been widely decried as torture, or at least as cruel and inhumane treatment. Yet temperatures at this level are not unusual in many US prisons, especially in the South, and rarely arouse resistance from anyone but the prisoners themselves. The New Hampshire hunger strikers gave up after about a week. But their protest highlights the brutal and sometime deadly conditions that persist in America’s prisons every summer.

In one high-profile case in 2009, Marcia Powell, a 48-year old inmate at Arizona’s Perryville Prison, was baked to death in the midday sun. Powell, whom court records show had a history of schizophrenia, substance abuse, and mild mental retardation, was serving a 27-month sentence for prostitution. On a day when the Arizona sun had driven the temperature to 108 degrees, she was parked outdoors in an unroofed, wire-fenced holding cell while awaiting transfer to another part of the prison. A deputy warden and two guards had been stationed in a control center 20 yards away, but nearly four hours had passed when she was found collapsed on the floor of the human cage. Doctors at a local hospital pronounced Powell comatose from heat stroke, and she died later that night after being taken off life support. (Two local churches stepped in to provide a proper funeral and burial.) The Maricopa County Medical Examiner ruled the death an accident, caused by “complications of hyperthermia due to environmental heat exposure.” This despite the fact that Powell had blistering and first and second degree “thermal injuries” on face, arms, and upper body.

Following Powell’s death, the Arizona Department of Corrections banned most uses of unshaded outdoor holding cells in Arizona, except in “extraordinary circumstances.” Most Southern states already restrict their use. But baking in the sun is only one of many ways to die in America’s prisons in the summertime. Recent years have seen scattered reports of heat-related prison deaths in California and Texas, among others. The prevalence of mental illness among the victims may be linked to anti-psychotic drugs, which raise the body temperature and cause dehydration, and at the same time have a tranquilizing effect that may mask thirst.

In 2006, 21-year-old Timothy Souders, another mentally ill prisoner, died of heat exhaustion and dehydration at a Jackson, Michigan prison during an August heat wave. For the four days prior to his death, Souders had been shackled to a cement slab in solitary confinement because he had been acting up. That entire period was captured on surveillance videotapes, which according to news reports clearly showed his mental and physical deterioration.

The vast majority of US civilian prisons and jails are not air conditioned. In contrast, the US made a point of building new air-conditioned facilities for prisoners at Guantanamo Bay, and phasing out the older structures. In Texas, only 19 of 112 prisons have air-conditioning. Earlier this summer, the chair of Texas State Senate’s Judiciary Committee, John Whitmire (D-Houston), told the Houston Chronicle that enduring the heat is “part of the reality of going to prison. There are a lot of inconveniences to serving time. There’s no question it’s hot.” He said he thought few Texans would be sympathetic to the prisoners’ suffering.

Apparently anticipating a similar lack of sympathy, the Florida Department of Corrections proudly advertises the absence of air-conditioning in most of its prisons. On a web page that debunks a host of “misconceptions” that might indicate soft treatment of Florida’s prisoners, it assures readers that the majority of inmates live without air-conditioning or cable television.

This post also appears on Solitary Watch.