<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/katerkate/4961855628/">katerkate</a>/Flickr

Long before the war on terror, there was the war on crime. And as much as 9/11 was a watershed event, our response to the attacks, and the resulting erosion of civil liberties, finds longstanding precedent in America’s criminal justice system.

In an article titled “Exporting Harshness: How the War on Crime Helped Make the War on Terror Possible,” Georgetown University law professor and former public defender James Forman Jr. argued against the widely accepted notion that “the war on terror represents a sharp break from the past, with American values and ideals ‘betrayed,’ American law ‘remade.'” Forman continued, “I suspect it is both too simple and ultimately too comforting to assert that the Bush administration alone remade our justice system and betrayed our values.” Instead, he wrote, “our approach to the war on terror is an extension—sometimes a grotesque one—of what we do in the name of the war on crime.…

As the world’s largest jailer, we are increasingly desensitized to the harsh treatment of criminals. We have come to accept such excesses as casualties of war—whether on crime, drugs, or terror. Indeed, more than that, we no longer see what we do as special, different, or harsh. Certain practices have become what David Garland calls “the taken-for-granted features of contemporary crime policy.” In part for this reason, despite the mounting evidence regarding secret memos, inhumane prison conditions, coercive interrogations, and interference with defense lawyers, the Bush administration’s approach to the war on terror went largely unchecked and unchanged. (H/T Prison Law Blog)

In his 2007 book, Governing Through Crime: How the War on Crime Transformed American Democracy, University of California-Berkeley professor Jonathan Simons also looked for the roots of these excesses. “Fear of sudden and terrible violence was a major feature of American life long before September 11, 2001,” he wrote. “The collapsing towers were only the latest—and most lethal—of a series of spectacular scenes of violence that have unfolded at the centers of our large cities since President Kennedy was shot to death in Dallas with a mail-order rifle in 1963.”

In the subsequent decades, Simon wrote, “American have built a new civil and political order, values like freedom and equality have been revised in way that would have been shocking…in the late 1960s, and new forms of power institutionalized and embraced—all in the name of repressing seemingly endless waves of violent crime…

The terror attacks of 9/11 have created a kind of amnesia wherein a quarter-century of fearing crime and securing social spaces has been suddenly recognized, but misidentified as a response to an astounding act of terrorism, rather than a generation-long pattern of political and social change. Just as we now see the war on terrorism as requiring a fundamental recasting of American governance, the war on crime has already wrought such a transformation—one which may now be relegitimized as a “tough” response to terrorism.

Many historians trace the birth of the war on crime to the mid-1960s—specifically, to Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign, with his rhetoric of “crime in the streets” and the need for “law and order.” Ever since then, politicians have exploited the fear of violent crime and its perpetrators to enact ever more draconian laws and policies. The war on crime was joined by the war on drugs, which was launched by Richard Nixon and gained traction under Ronald Reagan. One crime bill after another flew through Congress with broad bipartisan support, and more and more state and federal money was redirected used to expand law enforcement and to build and maintain prisons. From 1970 through 2005, America’s prison population octupled.

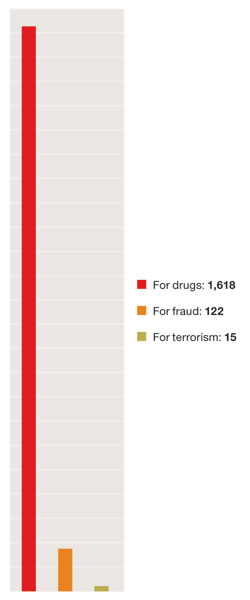

Delayed-notice search warrants issued under the expanded powers of the Patriot Act, 2006–09. Chart is from New York magazine; click on it to read Ben Wallace-Wells’ recent piece on the Patriot Act.In the 1990s, even as crime declined sharply, Bill Clinton championed two of the harshest pieces of criminal-justice legislation ever passed: The Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, enacted with broad bipartisan support following the Oklahoma City bombing, undermined the habeas corpus rights of American prisoners long before the Bush administration sought to withhold them from so-called enemy combatants. AEDPA placed severe limitations on prisoners’ ability to challenge death sentences—or life sentences, or unjust convictions—in federal courts, even when they had obtained new evidence of their innocence.

Delayed-notice search warrants issued under the expanded powers of the Patriot Act, 2006–09. Chart is from New York magazine; click on it to read Ben Wallace-Wells’ recent piece on the Patriot Act.In the 1990s, even as crime declined sharply, Bill Clinton championed two of the harshest pieces of criminal-justice legislation ever passed: The Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, enacted with broad bipartisan support following the Oklahoma City bombing, undermined the habeas corpus rights of American prisoners long before the Bush administration sought to withhold them from so-called enemy combatants. AEDPA placed severe limitations on prisoners’ ability to challenge death sentences—or life sentences, or unjust convictions—in federal courts, even when they had obtained new evidence of their innocence.

Clinton also signed the Prison Litigation Reform Act, ostensibly aimed at curbing frivolous lawsuits by inmates. “What the law has done instead,” noted the New York Times in a 2009 editorial, “is insulate prisons from a large number of very worthy lawsuits, and allow abusive and cruel mistreatment of inmates to go unpunished”—long before we began hearing horror stories from Guantanamo Bay, Abu Ghraib, Bagram, and the secret CIA prisons spawned by the war on terror.

Anne-Marie Cusac, who spent the decade prior to 9/11 reporting on abuses in US prisons, wrote in the Progressive after the Abu Ghraib scandal broke: “Reporters and commentators keep asking, how could this happen? My question is, why are we surprised when many of these same practices are occurring at home?” Cusac continued:

In February 1999, the Sacramento Sheriff’s Department settled a class-action lawsuit alleging numerous acts of torture, including mock executions, where guards strapped inmates into a restraint chair, covered their faces with masks, and told the inmates they were about to be electrocuted. When I read a report in The Guardian of London of May 14 that it had “learned of ordinary soldiers who…were taught to perform mock executions,” I couldn’t help but remember the jail.

Then there’s the training video used at the Brazoria County Detention Center in Texas. In addition to footage of beatings and stun gun use, the videotape included scenes of guards encouraging dogs to bite inmates.…

[Arizona’s] Maricopa County is well known for its practice of requiring inmates to wear pink underwear, and it is notorious for using stun guns and restraint chairs. In 1996, jail staff placed Scott Norberg in a restraint chair, shocked him 21 times with stun guns, and gagged him until he turned blue, according to news reports. Norberg died. His family filed a wrongful lawsuit against the jails and subsequently received an $8 million settlement, one of the largest in Arizona history. However, the settlement included no admission of wrongdoing on the part of the jail.

The Red Cross also says that inmates at the Abu Ghraib jail suffer “prolonged exposure while hooded to the sun over several hours, including during the hottest time of the day when temperatures could reach [122 degrees Fahrenheit] or higher.” Many of the Maricopa County Jail system inmates live outdoors in tent cities, even on days that reach 120 degrees in the shade. During last year’s heat wave, the Associated Press reported that temperatures inside the jail tents reached 138 degrees.

Cusac goes on to document other US prison abuses that many Americans decried in the context of the war on terror—stress positions, torturous restraints, rape by guards, and long-term solitary confinement. Indeed, Army Spc. Charles Graner, convicted as the ringleader in the Abu Ghraib prison abuse scandal (and recently released from a military jail at Fort Leavenworth), honed his skills at Pennsylvania’s state prisons, where guards have admitted to beating prisoners—and were accused of placing a razor blade in one inmate’s food.

Both Clinton’s AEDPA and the later Patriot Act ultimately have done far more to rein in the rights of the accused and prosecute everyday lawbreakers—including drug offenders and undocumented immigrants—than to round up actual terrorists. If the war on crime fed the war on terror, then the war on terror has returned the favor. And all of it has happened with the approval of both major political parties, virtually guaranteeing that the legacy of 9/11 will be an endless war at home.