Richard Aoki at a 1968 Black Panthers rally California WatchThe Center for Investigative Reporting has a fascinating new story about Richard Aoki, a ’60s Berkeley activist who joined the Black Panthers, helped arm the militant group, and became known as a fierce radical—all while working for the Federal Bureau of Investigation. This revelation has upended the reputation of the man Panthers cofounder Bobby Seale praised as “a Japanese radical cat.” It also adds another chapter to the FBI’s long history of using undercover informants to surveil extremists, both real and imagined.

Richard Aoki at a 1968 Black Panthers rally California WatchThe Center for Investigative Reporting has a fascinating new story about Richard Aoki, a ’60s Berkeley activist who joined the Black Panthers, helped arm the militant group, and became known as a fierce radical—all while working for the Federal Bureau of Investigation. This revelation has upended the reputation of the man Panthers cofounder Bobby Seale praised as “a Japanese radical cat.” It also adds another chapter to the FBI’s long history of using undercover informants to surveil extremists, both real and imagined.

An FBI agent first recruited Aoki in the late 1950s and asked him to gather information on various leftist groups. “The activities that he got involved in was because of us using him as an informant,” his original FBI handler told reporter Seth Rosenfeld. Aoki went on to report on the Communist Party, the Socialist Workers Party, the Young Socialist Alliance, and the Vietnam Day Committee before joining the Black Panthers in 1967.

He became the organization’s most prominent nonblack member and was named “Field Marshall at large.” Yet as informant “T-2,” Aoki was secretly reporting on its activities. His career as an FBI asset is recorded in documents obtained via Freedom of Information Act requests. Rosenfeld told me that the documents do not mention whether the Feds asked Aoki to join the Panthers.

Aoki also helped arm the Panthers. None of Rosenfeld’s FBI reports mention that Aoki gave weapons to the group, so it’s not clear if he did so with the agency’s knowlege or blessing. In his memoir, Seale recalled that he and fellow Panther Huey Newton had prodded Aoki to give them guns from his personal collection: “We told him that if he was a real revolutionary he better go on and give them up to us because we needed them now to begin educating the people to wage a revolutionary struggle. So he gave us an M-1 and a 9mm.” Either way, Aoki later took credit for contributing to “the military slant to the organization’s public image”—an image that, Rosenfeld writes, eventually “contributed to fatal confrontations between the Panthers and the police.”

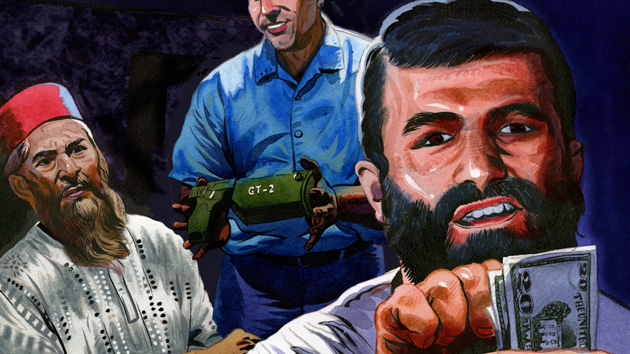

The broad contours of Aoki’s tale echo those of the cases described in “The Informants,” Trevor Aaronson’s award-winning Mother Jones investigation into the FBI’s use of informants to identify and track would-be Muslim American extremists. But where Aoki may have been an old-fashioned informant among actual militants, the cases Aaronson reported on reveal a radical shift in the use of informants after 9/11:

The main domestic threat, as the FBI sees it, is a lone wolf.

The bureau’s answer has been a strategy known variously as “preemption,” “prevention,” and “disruption”—identifying and neutralizing potential lone wolves before they move toward action. To that end, FBI agents and informants target not just active jihadists, but tens of thousands of law-abiding people, seeking to identify those disgruntled few who might participate in a plot given the means and the opportunity. And then, in case after case, the government provides the plot, the means, and the opportunity.

Rosenfeld is still fighting to get the FBI to release additional documents on Aoki. But the ones he has so far do not suggest that he was an agent provocateur or an opportunist in the mold of FBI assets like “superinformant” Shahed Hussain, who earned $100,000 setting up stings for Muslim “radicals.”

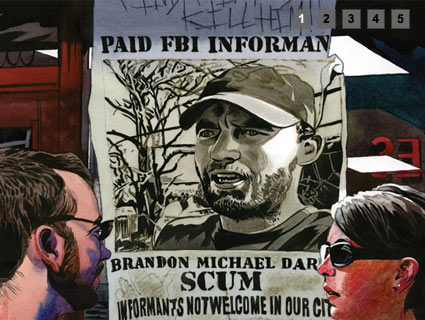

The contemporary informant Aoki resembles most may be Brandon Darby, the anarchist organizer-turned-FBI plant whom Josh Harkinson profiled as part of MoJo‘s special report on terrorism informants. Darby seemed to be a true believer before he snitched on a band of young radicals who were eventually convicted of conspiring to set off firebombs at the 2008 Republican convention. “I feel very morally justified to do the things that I’ve done,” Darby, now an acolyte of the late Andrew Breitbart, told Harkinson.

What motivated Aoki’s chameleon-like behavior and how he reconciled it with his apparently sincere commitment to radical leftist politics may remain mysteries: He committed suicide in 2009. When Rosenfeld asked him about his role as an informer two years before his death, Aoki didn’t fully deny it. “People change,” he said. “It is complex. Layer upon layer.”

This post has been updated.

Front page image of Richard Aoki by California Watch/Flickr