<a href="http://www.fbi.gov/news/updates-on-investigation-into-multiple-explosions-in-boston/updates-on-investigation-into-multiple-explosions-in-boston">FBI</a>

You know how it’s supposed to work. There’s a movie about the future with a bad guy and some good guys. The good guys scan a picture of the bad guy into a computer, the computer quickly cross-references the image against enormous, ominous databases, up pops his name, and they go after him.

Not so much in real life.

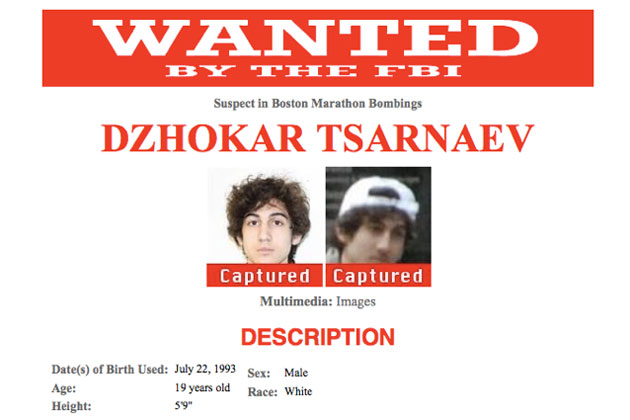

For a few hours each year, during the Boston Marathon, the 600 block of Boylston Street is the most photographed place on Earth, what with all the family, friends, tourists, news crews, and commercial photographers. So it was a perfect setting for the FBI to make use of facial-recognition technology. But even though Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev’s images existed in official databases, the brothers were not identified that way—because we just aren’t that advanced yet.

Facial-recognition technology turns a photograph into a biometric template that can be matched with photos attached to names in other databases. Last summer, the FBI launched a $1 billion facial-recognition program called the Next Generation Identification (NGI) project as a pilot in several states. Once fully implemented, the security program is designed to include some 12 million searchable mug shots as well as voice recognition and iris scans. The FBI would not confirm if the program is being piloted in Massachusetts, but even if it were, it may not have been useful since it is unclear whether the brothers had criminal records. But the FBI also has access to the State Department’s passport and visa facial-recognition databases, and can get similar DMV information from the 30-odd states that have it, including Massachusetts. Both brothers had Massachusetts driver’s licenses, so it would seem they would be traceable. (Tamerlan’s name was also included in a federal government travel-screening database in 2011 after the FBI investigated him for possible terrorist activity at Russia’s request, but the government’s databases related to immigration, customs, and border-related interactions do not yet have facial-recognition capabilities.)

But in order for facial recognition to work, you need a high-quality frontal photo of the face you want matched. If you have that, research shows, you can pick a suspect out of more than a million mug shots 92 percent of the time. But the image that the FBI captured of the Tsarnaevs from surveillance camera images was grainy and taken from far away, which would have drastically limited the effectiveness of the technology.

Paul Schuepp, CEO and president of Animetrics, one of the facial-recognition companies the FBI contracts with, says that by the time the suspects’ faces were zoomed in on, there were only a few dozen pixels per face. “When you’ve got like five pixels between the eyes, you’re done,” he says. “There’s just not enough data on the face [and] the computer has a impossible time.” Schuepp says that the Tsarnaevs’ faces were also angled away from the camera, and Tamerlan’s sunglasses and hat didn’t help either. “Some [news] networks were saying they got good pictures, but the pictures really sucked,” he says.

Instead, the FBI released the photos of the two suspects last Thursday and depended on old-fashioned eyeballs to do the work. “It’s likely that the breakthroughs in the case were made by sharp-eyed investigators,” Bloomberg News reported, “spotting one of the suspects dropping a bag at the site of one of the two bombings in the surveillance footage, then matching the face with an image from the security camera of the 7-Eleven in Cambridge” that was the scene of an armed robbed on Thursday. Jeff Bauman, the runner who lost both his legs in the explosion, also helped ID the suspects after he woke up in the hospital.

“Even at a distance, as a human being you could recognize that person,” Schuepp says.

But facial-recognition technology has been used successfully in another bombing case; it helped in the investigation of of the Times Square bombing attempt in in 2010. And the FBI is hard at work to expand the NGI program. Bloomberg News reported that “the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the NYPD have also expressed interest in more exotic technologies, including one that analyzes people’s gait for clues as to whether they’re carrying a bomb. Programmers are developing machine vision techniques that can link images of the same person across different video cameras or spot behaviors that are out of the ordinary for a certain setting (e.g., leaving a bag unattended in a public place).”

Civil libertarians worry that eventually these kinds of technologies could soon become all too effective, tracking people in the streets whether they’re suspected of a crime or not. And the Rutherford Institute, a civil liberties group, calls the NGI a huge boondoggle. “With technology moving so fast and assaults on our freedoms, privacy and otherwise, occurring with increasing frequency,” charged the group in a September 2012 statement on the NGI project, “there is little hope of turning back this technological, corporate, and governmental juggernaut.”

This article has been revised.