When I ask Christine Hernandez, a mother of four, slender in stature and bold in manner, how best to scout for abandoned homes—the bleak dwellings with the boarded-up windows and ripped-out drywall, their innards packed with leftover syringes, rotting debris, and the peculiar loot of previous dispossessed tenants—she says it’s best to send someone who won’t draw too much suspicion from cops or neighbors. “I’m a woman, and small,” she notes. “Not super intimidating, you know?”

It was about two years ago when Hernandez, who works at a community development organization, and her husband, Emilio, a painter, were forced to leave their ramshackle home in Oakland, California, after trying to get their landlord to make repairs. They started touring listings and seeking out “For Rent” signs in windows. But in the nutso housing crisis plaguing the Bay Area, where one-bedroom apartments in Oakland rent for more than $2,000 a month—never mind a home with space for a family of six—they found themselves, like so many others, hopelessly priced out. What they did notice was a shocking abundance of forsaken properties. They started performing reconnaissance. “A lot of them were already occupied, so, you know, that’s that,” she says. “A lot of them had burn damage, so you can’t really do much with that.”

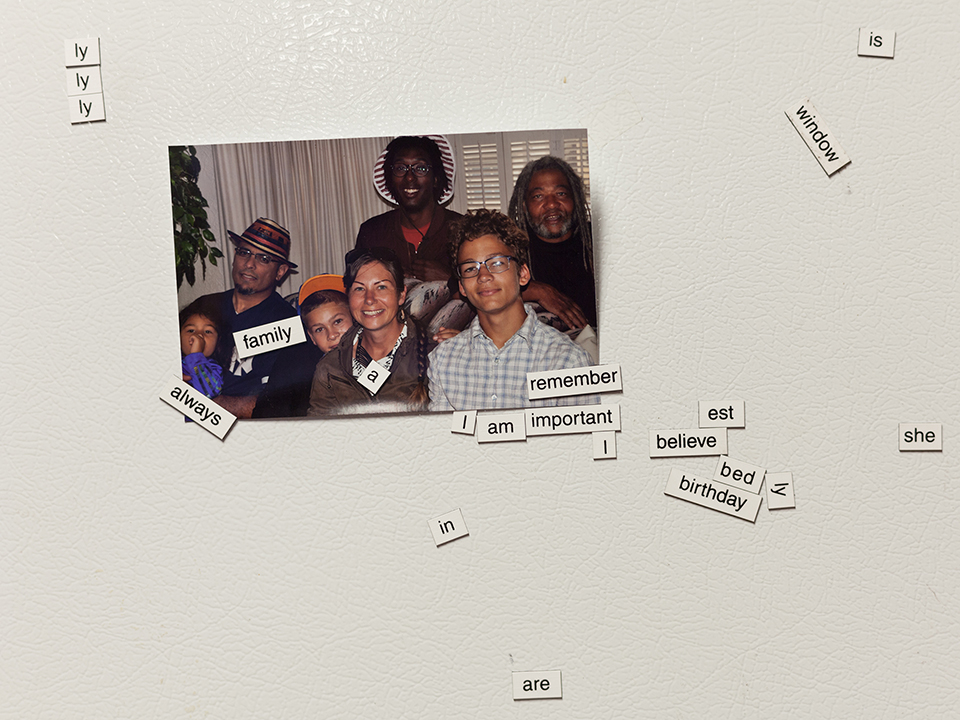

Fifteen-year-old Marcus opens the gate to the Hernandez home. The Hernandez family lives behind a locked fence in order to prevent unannounced and potentially unlawful entry by people trying to get them out of the home.

Then on a clear October morning in 2015, they found a three-bedroom, one-bath house that had been a haven for drugs and prostitution. They pried open a section of the chain-link fence surrounding the property, scurried inside, and explored by flashlight. The kitchen had no counter, no sink, no pipes. Burn marks scoured the home. “It was a total mess,” says Hernandez, but a mess could be cleaned up. They got to work.

The right to adequate housing—not just four walls and a roof, but “a safe and secure home and community in which to live in peace and dignity”—is decreed by the United Nations, but you wouldn’t know it by looking around California, where nearly a quarter of the nation’s homeless people live. The housing crisis is often described as a shortage, the only solution being that we build our way out of it. But for every American living on the street, there are 13 empty, off-market units. In Oakland, where buyers routinely offer hundreds of thousands of dollars over asking prices, there are nearly four vacant properties for every homeless person. It’s not so much an issue of scarcity, but of distribution.

A snapshot of Christine Hernandez and her family in West Oakland, California

Christine Hernandez and her daughter Sofia Lina, four years-old, repot plants in their Fruitvale, California, backyard.

Emilio Hernadez holds a bullet that entered Madeleine Hernandez’s bedroom.

Squatting, or “occupying,” as its practitioners tend to prefer calling it, is a shaky existence, Hernandez’s family immediately discovered. On their first day, they encountered an outraged neighbor. “She was like, ‘You have kids? You’re going to be living in that filth and squalor?'” The cops came later, walking in on them as they were patching the walls, interrogating them about how they had gotten inside. A nearby house would occasionally host illicit gambling nights that would “inevitably involve gunfire.” Two days before their eldest daughter’s 17th birthday, a bullet entered her bedroom window, bounced around, and slammed a hole in the wall two feet from her head. She still has the slug, a smashed-up metal keepsake, on her dresser.

But the worst was when a representative from a bank busted in. Christine and Emilio arrived home to find the front door smashed and the locks changed. The house was ransacked, their valuable possessions stolen. The water was turned off and the power had been shut down. Flyers from a company called M&M Mortgage Services, which offers “debris removal” and “eviction services,” festooned the house: “This property was found to be vacant and/or unsecured,” they read. “It has been secured against entry by unauthorized persons to prevent possible damage.” The company operatives had let the family’s dog loose and it went missing for days.

Scouring the internet for information on how to fight back, Hernandez came across an organization run by an Oakland man who had used a little-known law called “adverse possession” to gain ownership of a home he’d occupied for more than a decade. Passed down from common law, the legal doctrine varies from state to state, but the basic gist is that anyone can legally claim an abandoned property if he or she occupies it and pays its back taxes for a set time and as long as no one else steps forward and proves ownership.

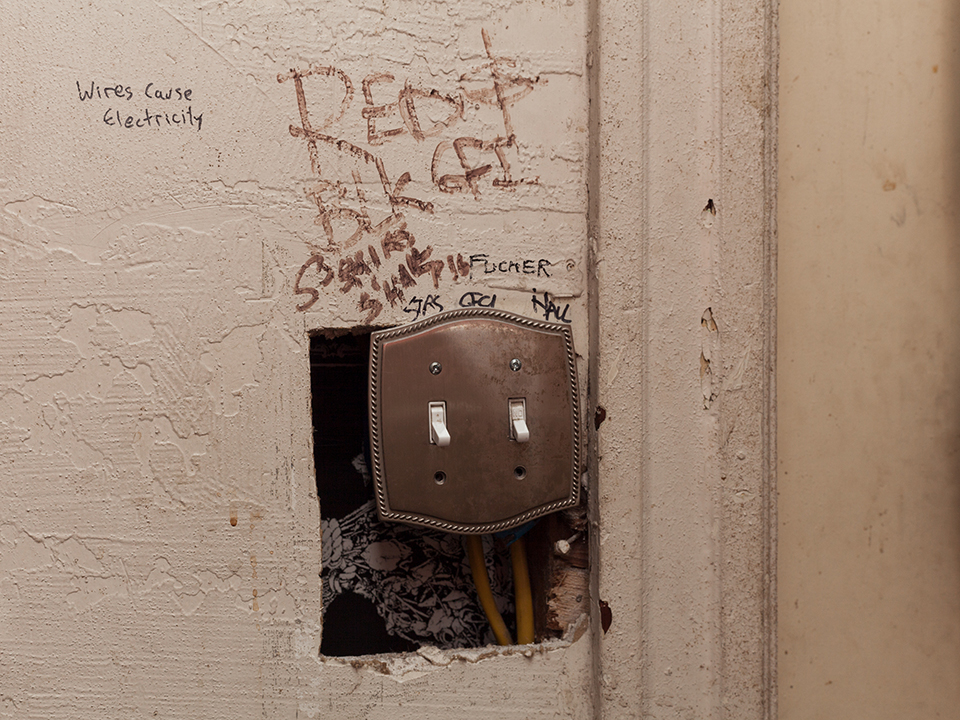

Outdated electrical wires extend from the walls of renovated squat properties. Legal prosecution and future instability prevent squatters from ongoing renovation investment in properties that they may be forced to vacate in the near future.

Vaughn, Marcus, and Sofia Lina Hernandez (left to right) share a birthday breakfast for Emilio in their Fruitvale home.

Christine Hernandez and her daughter Sofia Lina rest on the hammock in their backyard.

The man was Steven DeCaprio, and his organization, called Land Action, was dedicated to helping squatters. Hernandez and her family went off to find him.

DeCaprio is 45 years old, with a salt-and-pepper crew cut and beard. About 15 years ago, unemployed and recently evicted, he was living out of his van when he first saw the home that he now owns—a turn-of-the-century bungalow in a poor West Oakland neighborhood. Plywood stood in for the front door, the back of the house hung off the foundation, the kitchen floor was burned down to charred beams, and an acacia tree had grown through a hole in the roof. The top floor, open to the sky, was littered with animal carcasses.

Steven DeCaprio provides legal and administrative advice from Berkeley, California’s Meiklejohn Civil Liberties Institute, where he is the executive director.

He researched property records and learned that the previous owner had died in the 1980s and no one had claimed the house. DeCaprio broke in, and with a crew of friends he started what would become a yearslong process of rehabilitating the property. They added locks, installed a solar power system, drew baths over a propane stove, and had fires in the backyard. “Wild West meets cyberpunk,” he says.

After countless run-ins with the police, DeCaprio finally gained title to the home. In California, adverse possession requires five years of paying taxes and navigating a bureaucratic maze of tax assessors, the courthouse, property records, and in some instances litigation to force a county to accept tax payments. It also requires an extraordinary amount of good fortune: Until they become adverse possessors, squatters are trespassers, subject to criminal charges whether an abandoned property’s owner complains or not.

A light fixture hangs from the ceiling of a renovated squat property.

Steven DeCaprio enters his West Oakland home, acquired through persistent, law-abiding squatting.

A cot welcomes guests in the living room of Steven DeCaprio’s West Oakland home.

DeCaprio’s idea to create Land Action came after the Supreme Court’s infamous 2010 Citizens United ruling, when he had an epiphany over the phrase “Corporations are people.” “Homeless people should form a corporation,” he thought. He modeled Land Action off a tactic he had seen real estate speculators use: They form a collection of limited liability corporations to act as titleholders to conceal their ownership. Land Action would function as a title holding company to shield squatters until their paperwork cleared.

DeCaprio pursued a law degree through an independent study program and passed the bar exam. The State Bar of California has declined to issue his law license, saying that an old misdemeanor trespass charge may make him ineligible on moral grounds. He is appealing. But with or without the license, he’s become a squatting guru, leading seminars to often desperate people up against eviction.

This activism has come with costs. Not long ago, DeCaprio was facing several years in jail and tens of thousands of dollars in fines for felony conspiracy charges stemming from assisting two Oakland squatters in 2015. When those charges were finally dropped in late 2017, DeCaprio and his colleagues interpreted it as a confirmation that adverse-possession claims might be a viable strategy for housing for at least some of the Bay Area’s burgeoning homeless population.

On a stormy night in January, I tagged along with DeCaprio as he drove to a city commission meeting about a homeless encampment in Berkeley. As he steered through the rainy streets, he said that in his nearly two decades of working on housing rights, he’d “never seen such an acute amount of displacement and homelessness.” The dot-com boom and the foreclosure crisis were nothing compared with the speculation that’s occurring now, “this new real estate bubble that keeps expanding.”

Shown in an upstairs bedroom of his West Oakland home, Steven DeCaprio recounts ongoing legal trials and persecution endured in order to maintain his law-abiding squatting.

Lasting hints of humor, community spirit, and teamwork essential to renovate Stephen DeCaprio’s West Oakland squat decorate the walls surrounding recently updated electrical wires.

A perimeter fence and large dog named Remus protected Steven DeCaprio from police as well as burglary over the years.

For some squatters, adverse possession is a goal, but it’s not necessarily the goal. “Most of the people I’ve worked with, squatting has been more of a temporary solution to their problems,” says DeCaprio. “You can get a lot accomplished if you have a few months or a few years in a house to get your shit together. When you have no other housing available and you’re squatting, every fucking day is a victory.”

Take Hernandez. After the house was put up for auction, she brainstormed with Land Action and went back armed with a stack of bright yellow notices to hand out to potential bidders: “[This home]…is currently occupied by a family wishing and intending to continue tenancy,” the flyers read. “We know our rights and intend to assert and defend them.”

The place they had called home for the previous two years—the one they had relieved of layers of rotting refuse, and where they had installed appliances, gotten the plumbing and electricity up and humming, won over the neighbors, and planted a garden—was the first property auctioned that day, for one penny over the opening price to a sole bidder who intended to flip it. Soon, an eviction notice arrived.

Hernandez filed a motion to quash, which stated that her family hadn’t been properly served. “A lot of these eviction mill lawyers are not putting the names of the occupants on the complaints,” says DeCaprio. It’s a tactic used to expedite an eviction, he says. “These attorneys are making their money by volume and not really doing their jobs, and actually benefiting the speculators and the developers and the landlords who get these really fast evictions.”

“They know our names,” says Hernandez, when I visit her. “We met the new owner. We sat at this table. I made sure he had an opportunity to see this,” she adds, gesturing around the dining room. On a computer nearby, a slideshow of the house’s transformation plays—holes in walls are patched and painted, plumbing and appliances are installed, burn marks disappear. As she talks, her four-year-old daughter, Sofia Lina, occasionally interrupts with a facetious grin and a whisper, each time bearing new items in her tiny hands. “I want to show you my toys.” “Will you draw a circle on this?” “I want you to hear this song. It’s the Queen of Pony song.”

“But he was, you know, it’s an investment for him,” Christine says. “The longer we’re here, the more it cuts into his potential profit.”

In January, the court granted Hernandez’s motion; the owner will have to restart the eviction process. She’s been preparing a backup plan. “There’s a house that I’m looking at that isn’t occupied, and it has a hole in the roof and some other damage. It has a lot of debris in the yard,” she says. “A person recently inherited the house. I want to reach out to that person and say, ‘We’re happy to completely clean your house. We’ll paint it. We’ll fix your roof. We’ll take care of any business that needs to be taken care of, in exchange for you allowing us to live there for some agreed upon period of time.'”

Hernandez looks up. “We did this because we needed to do it,” she says, “and we do it without apology.”

Christine Hernandez’s youngest daughter, Sofia Lina, plays on the couch of their Fruitvale home.