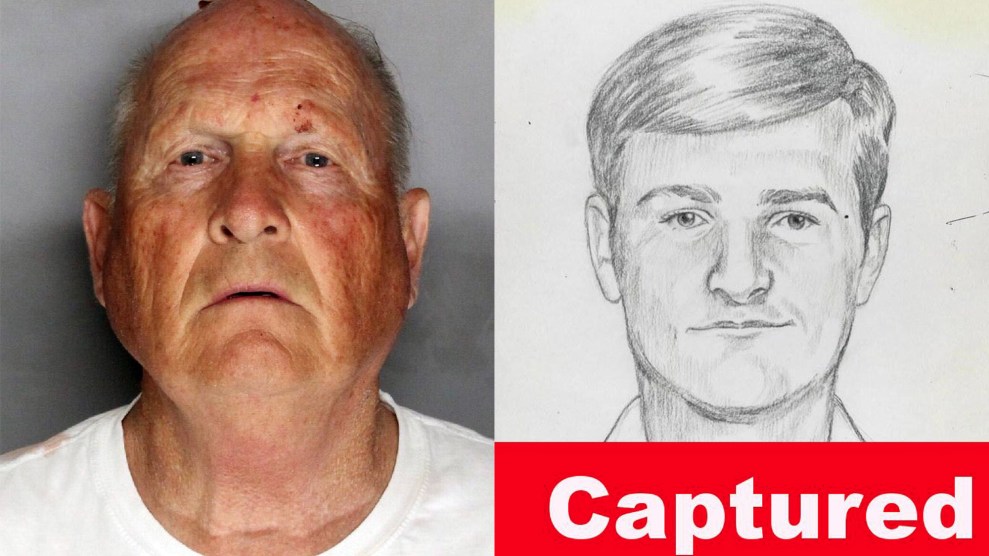

Golden State Killer suspect Joseph DeAngelo (left) and a police sketch of the suspected serial killerSacramento County Sheriff's Department/FBI/Zuma

When the serial murderer now known as the Golden State Killer committed his crimes across California in the 1970s and ’80s, he was extremely careful not to leave behind fingerprints or other physical evidence. Earlier this week, police finally arrested a suspect, 72-year-old Joseph James DeAngelo, based on the DNA he allegedly shed at his crime scenes.

While using DNA to crack cold cases is not unusual, the method used to find DeAngelo is relatively new: Investigators tracked him down through public genetic profiles posted online by his family members. For years, the suspect’s “abandoned” DNA had not offered any leads about the killer’s identity; it did not turn up any matches in the FBI’s national DNA database. A breakthrough came only after law enforcement uploaded genetic information from the crime scene samples into the online genealogy database GEDmatch and followed the results to distant relatives of DeAngelo. After confirming he was a match with the crime scene DNA, police showed up at DeAngelo’s house outside Sacramento on Tuesday.

To understand how this groundbreaking forensic search worked, and what it means for our genetic privacy, I spoke with New York University Law Professor Erin Murphy, an expert in forensic evidence and author of Inside the Cell: The Dark Side of Forensic DNA.

Mother Jones: How were the police able to identify Joseph James DeAngelo?

Erin Murphy: I would guess that the police first ran a traditional test of the DNA sample from the crime scene. California is one of the states that allows a familial search in its convicted offender database. That means using the database of convicted offenders’ DNA to turn all their family members into possible suspects. They can then look and see if there is anyone who looks very similar. Not unlike physical resemblance, genetic resemblance can be happenstance. If you run the search in a database, you are not going to get back one name; you get a list of names. And from that you whittle it down using genetic and nongenetic investigative methods. I imagine they did this first and it did not have any success, which is why they moved on to a public site.

What happened there is a little unclear. First, given what they said about how hard it was to narrow the search, it seems clear that he [DeAngelo] himself was not the person in the database. I have a bunch of questions of how exactly they uploaded the DNA sample. A lot of these sites look at different parts of the genome, and it’s unclear how they knew what segment of DNA to upload. Did the state forensic lab test the sample, using a kit that looks at the same markers that some of the forensic sites do? Did they submit the sample to one of these sites and then download the raw data, which they then in turn uploaded to GEDmatch? There is also a more technical question: Most genealogy sites use a genome testing technique that looks at something called SNPs, whereas most forensic tests look at STRs. Does the state lab have the capacity now to test the same SNPs used in genealogy? That would be interesting to know.

Whatever the case, after the upload they effectively got back a list of names. From there, presumably, they eliminate anybody who doesn’t fit. Maybe they don’t have a California connection, or are the wrong age or whatever. Then you continue to narrow it down using public information like military history or criminal history or financial records et cetera. You keep winnowing down the list using investigation techniques. But given how many names you would start with, recognizing that none of those names was the suspect’s names—they were at best a father or brother or relative of the suspect—they really had to have a lot of luck.

MJ: And to confirm the genetic match, the investigators obtained samples of Joseph James DeAngelo’s DNA ?

EM: This is an area of the law that I think is problematic. Essentially anything that you abandon in the world is fair game. That includes a tiny number of cells on a cup you threw in the trash. As long as the police lawfully obtained that piece of DNA, they can do nearly anything with it. That doesn’t seem right, either.

I am disappointed that the police didn’t share their methods at the time they were extolling the virtues of the results of that method. If you think it’s worth it, why are you acting ashamed? The fact that they were so cagey shows they thought some people would find how they did it unsavory. But again, it’s hard to be angry in the face of a capture in a case like this.

MJ: What do we know about the genealogy site the police used, GEDmatch?

EM: It’s a volunteer-created site. It is not a private company that has been busy advertising, the way some of these other sites have. I haven’t been able to find out exactly how many profiles they have. 23 and Me has seven million profiles.

One interesting thing to me: To upload a profile you have to click a button saying you are adding “either your DNA or the DNA of a person for whom you are a legal guardian or have obtained authorization to upload their DNA.” The argument by law enforcement would probably be they have legal authorization to use the DNA sample. And even if they violated the rules of the website, that doesn’t clearly make it an unconstitutional act.

MJ: This method of identifying a suspect based on their relatives’ DNA has been used at least one time before. How common is it?

EM: I am sure this method has been used in other cases, too, but we only learn about it when there is a match. We don’t know in this case, if they collected more DNA from other people that didn’t match. Is the information in a database on the sheriff’s laptop somewhere? I think this sounds like a needle in and a haystack situation. One of the reasons we don’t do this sort of search on a national level is you would get so many leads it would be impossible to determine who you were looking for.

MJ: So are we likely to see DNA information from relatives of suspected criminals used to crack more cases?

EM: Obviously, the investigative resources they could put into this case were enormous. It likely took a lot of police power just to narrow down the list of results. But don’t get me wrong. When something works, people want to use it, especially in cases like this that have been cold for a long time and are high-profile. I don’t think this is the last time this will happen.

MJ: Can police also search for matching genetic information on popular consumer sites like 23 and Me, and Ancestry.com?

EM: 23 and Me [and AncestryDNA] require you to send in a vial of spit. That’s a logistical challenge for police. And I know 23 and Me only responds to legal process inquiries. They will not voluntarily expose information about their clients. So they are kind of shielding information.

There are a lot of warnings on these sites that they can’t guarantee your privacy. If it only affects me, it’s one thing. If I’m making a decision that affects my brother, my sister, my mother, my father, my children, essentially everybody I’m related to, I think that’s really different. I don’t know the answer to how best manage that problem, but I do think it’s a serious issue. One member of the family can essentially forfeit the genetic privacy of an entire family for generations. It could be unnerving down the road.

I have people in my family who love this kind of stuff. I’m really interested in genealogy in my own family ties and connections. I completely understand why people do these tests. There’s a lot of tech that makes our lives a lot more convenient and much more enjoyable, but has tremendous repercussions for personal privacy.

MJ: What else should people think about before sending in a swab of their spit for analysis?

EM: The first thing I would say is, no matter what site you are using it’s important to recognize you are making a decision not just for yourself. You are deciding something that could impact your whole family. If 2018 has taught us anything, it’s that nothing is truly private. Genetic information is something that can be very hard to control or draw back once it’s out there. You have to have your eyes open about that.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.