Hailshadow/Getty

Update, 2:45 p.m.: Clark County District Court Judge Elizabeth Gonzalez just issued a temporary restraining order blocking Nevada from either using or destroying the midazolam it illegally obtained from Alvogen. It’s unclear how the state will proceed regarding the execution that is scheduled for tonight.

Update, 10:45 a.m.: Alvogen, the company from which Nevada obtained midazolam, filed a lawsuit against the state Tuesday afternoon*. The company is alleging that despite a clear warning its product could not be used in executions, Nevada purchased the drugs by “subterfuge.” The suit says the state purchased the drugs through an “unsuspecting intermediary” who would not have sold the product if it had known the drugs were going to be used to put Dozier to death. The company is now demanding that Nevada return the drugs. A Clark County judge has scheduled a hearing over the matter for 9:00 a.m. Pacific, just hours before Dozier’s execution is scheduled to begin.

Scott Dozier is scheduled to die on Wednesday. The Nevada inmate has been on death row since 2007 for having shot and dismembered 22-year-old Jeremiah Miller in a drug-related crime in 2002. Eight days before the execution, the state announced that they would use a new combination of drugs to put Dozier to death.

“There are so many concerns and problems with this particular protocol they plan to use that there is a real risk of a botched execution,” Amy Rose, the legal director from the ACLU of Nevada, told Nevada Public Radio last week.

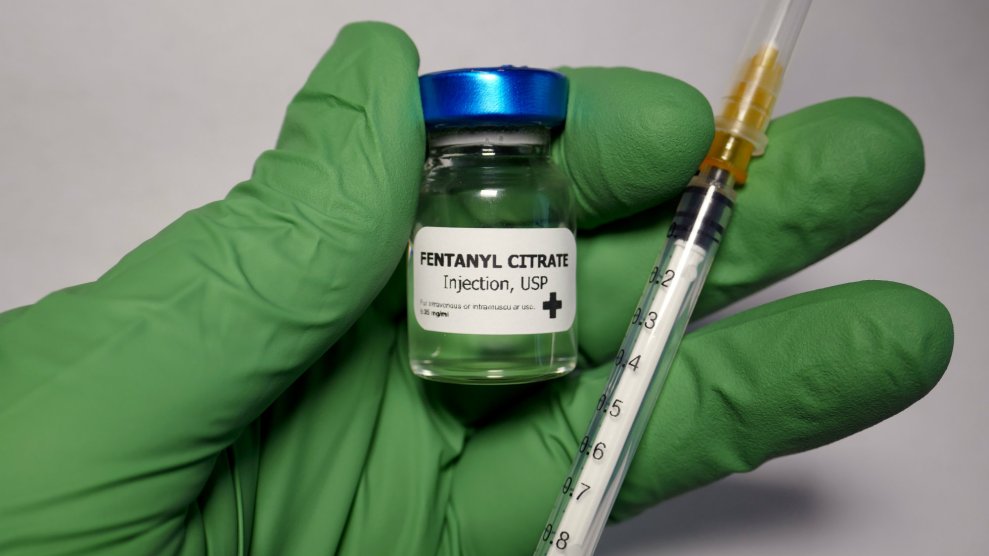

First, officials will administer midazolam, a controversial drug that has been blamed for several botched executions, to sedate him. They will then give him fentanyl, a powerful painkiller intended to stop his breathing, and cisatracurium, a muscle paralyzer that could make it impossible for Dozier to express any pain or discomfort he may be feeling. The ACLU of Nevada had filed a lawsuit earlier this month against the state asking it to publicly release all the information about the drug protocol. Prison officials released a “heavily redacted version of the protocol manual,” last week but Rose said this “just raises more questions and more concerns.”

Dozier was convicted of two murders; Miller‘s in 2002, and one in Arizona that only came to light after he was arrested in Nevada and an informant led investigators to the victim’s body. He was sent to Nevada’s death row in 2007. In 2016, he asked Clark County District Judge Jennifer Togliatti to skip remainder of his appeals, deciding that death was better than life in prison. What followed was a series of legal battles and setbacks, but eventually he was granted his wish.

Nevada, like many states that carry out the death penalty, has struggled to find drugs because, in recent years, drug manufacturers have refused to sell their products to prisons that intend to use them in executions. The state obtained fentanyl from Cardinal Health, a pharmaceutical wholesaler which is facing lawsuits that allege the company is profiteering off the opioid crisis by selling mass quantities of drugs to small pharmacies. The company from which it obtained midazolam is considering legal action. In a statement, US-based Alvogen said it “does not market, promote or condone the use of any of its approved prescription drug products, including midazolam, for use in state sponsored executions,” and the company would be exploring “legal recourse” to prevent Nevada from using the drug.

Since the combination of drugs Nevada will use to execute Dozier has never been tried before, it’s unclear how they will react with one another. Medical experts are particularly worried about the effects of cisatracurium, the muscle paralyzing drug. When the drug is injected, Dozier will be unable to move any part of his body, including using his diaphragm to breathe. “He will be dying of asphyxiation,” says Dr. Joel Zivot, an anesthesiologist at Emory University. “These inmates are drowning in their own saliva, but because they can’t move, they don’t indicate that they’re struggling.” Dr. Zivot describes this as a “sinister problem…If you observe this death, it will not strike you as unreasonable. Outwardly, this will look very calm.”

He will also become the first person in the United States executed with fentanyl, and that too is problematical. “In large doses, narcotics might make someone stop breathing,” Dr. Zivot explains. “When someone dies from a narcotics overdose, it’s not a painless death.”

The new protocol was only recently settled. Nevada had originally planned on using diazepem, another sedative to put Dozier to sleep. But several days before the execution was scheduled to occur, the state announced that it would use the controversial midazolam instead. The sedative, when used at the hospital or a doctor’s office is relatively harmless but has been blamed for several botched executions in the past. When the state of Arizona used midazolam to execute Joseph Wood in 2014, for example, he snorted and gasped for two hours before dying. When Arkansas executed Kenneth Williams last year, the inmate reportedly convulsed, jerked, lurched, and coughed for about 10 to 20 seconds after officials administered the midazolam.

Despite the uncharted waters, Nevada officials are not concerned about moving forward with the execution, and Dozier has remained committed to dying. His lead attorney Tom Ericsson said that despite legal advice to the contrary, Dozier has “made it very clear he doesn’t want anybody filing anything related to the drug protocol.” Dozier said as much during a telephone interview from death row. “Life in prison isn’t a life,” he told the Las Vegas Review-Journal. “This isn’t living, man. It’s just surviving.”