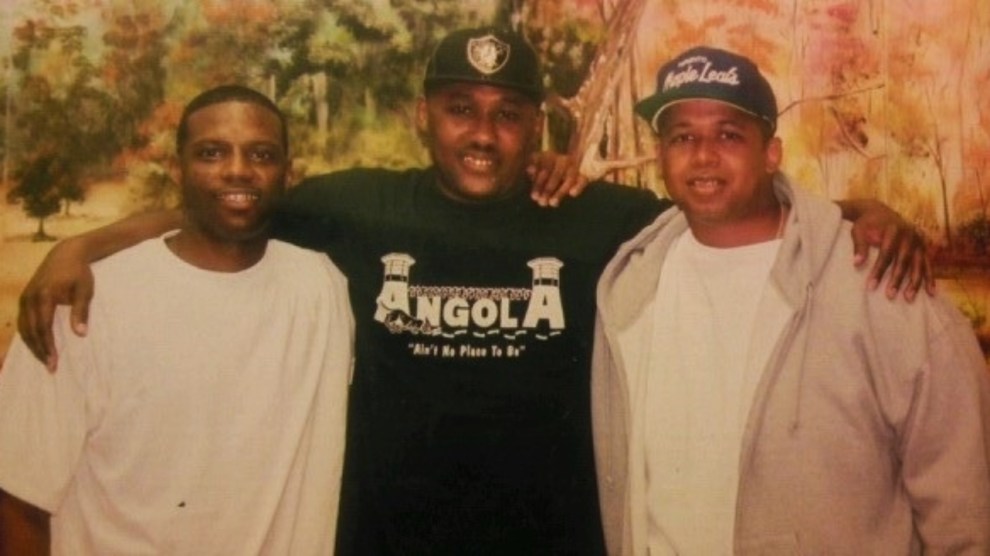

Glenn Davis (left) and his co-defendants in an undated photo at Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as AngolaInnocence Project New Orleans

In 1992, Glenn Davis was a teenager in Avondale, Louisiana, with a baby on the way when he was charged with murder. A witness claimed he saw Davis, along with two of Davis’ cousins, shoot and kill a drug dealer in a drive-by. Though there was evidence another man committed the crime and that the supposed eyewitness wasn’t even there during the shooting, this potentially exculpatory information wasn’t presented at the trial. Davis was convicted and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Some of the jurors on Davis’ case felt the evidence wasn’t strong enough to convict him. In fact, Davis was put away after 2 of the 12 jurors hearing his case voted for his acquittal. If Davis had lived in almost any other state, disagreement among the jurors hearing his case would have meant they were sent back to the deliberation room until they agreed. Davis was convicted because Louisiana is one of only two states that don’t require unanimity within the jury box.

But this year might be the last for non-unanimous juries in Louisiana. In November, voters will weigh in on a ballot measure to abolish juries that aren’t unanimous, an effort aggressively pushed by a broad bipartisan coalition of activists, lawmakers, and attorneys and overwhelmingly approved by the state Legislature in May. (In Louisiana, lawmakers have to approve ballot measures before voters decide on them.)

“The non-unanimous jury [law] hangs over Louisiana like a cloud,” Ed Tarpley, a former district attorney who spearheaded the effort to get the initiative on the ballot, told Mother Jones. “It has deprived citizens in our state of one of our most precious rights, which is the full protection of the right to trial by jury and the unanimity of the jury.”

Louisiana’s jury law is more than 100 years old and a remnant of the Jim Crow era, when the newfound political power of freed slaves created panic among whites and laws reinstating social and government control over black people were enacted in droves. Louisiana lawmakers who pushed for the measure’s inclusion in the state constitution in 1898 said it would resolve the problems created by allowing black people to serve on juries, calling it an effort “to establish the supremacy of the white race…to the extent to which it could be legally and constitutionally done.” Soon before the current state constitution was ratified in 1974, there was an effort to repeal the jury rule, but it lost traction.

In almost every state, requiring juries to reach unanimous decisions has always been a given. Angela Allen-Bell, a law professor at Southern University who has written extensively about the topic, told the Marshall Project in 2017 that a “vast amount of research on group thinking…suggests that unanimous juries are more evidence-driven (as opposed to verdict-driven) and that unanimous verdicts are more reliable, more careful, and more thorough.” As Tarpley put it, “How can you say someone has been convicted beyond a reasonable doubt” without a unanimous jury? Only one other state allows non-unanimous juries to decide whether to convict a person: Oregon, which instated its non-unanimous jury rule in 1934. (A state appeals court is hearing a challenge to that law.) Florida and Delaware allowed non-unanimous juries to impose the death penalty until the laws were ruled unconstitutional in 2016. Alabama still allows non-unanimous juries to sentence people to death.

There’s no question Louisiana’s law has had profound effects on justice in the state, which has the second-highest rate of exoneration in the country. An analysis this year by the Advocate newspaper found that of nearly 1,000 felony convictions over six years with jury data available, 40 percent had non-unanimous juries. Lawyers at the Innocence Project New Orleans (IPNO) told Mother Jones that similarly, about 40 percent of the clients they have helped exonerate were convicted by non-unanimous juries. And according to some experts, non-unanimous juries don’t incentivize members of the jury to thoroughly deliberate on the evidence of the case.

“These [jury] deliberations happen in two, three, four hours when someone’s life hangs in the balance,” Jee Park, executive director of IPNO, told Mother Jones. “We have interviewed dissenting jurors in our cases where they say that once [the jury] reached a vote of 10, they stopped talking, people were ready to go home.”

New Orleans resident Liz McCartney served on the jury in a felony burglary case last year. McCartney told Mother Jones she was one of two dissenting jurors who believed the defendant, who was black, was innocent.

“Going through the [jury] process was really disheartening,” she said. “It was clear when I started talking to the other jurors that they had made up their minds in the very beginning…I feel like I failed the defendant.”

Davis, who was an IPNO client, was released in 2007 and exonerated in 2010 after spending 15 years in prison. He is certain the non-unanimous jury rule played a role in his conviction—two of the three black jurors on his case voted that Davis be acquitted. In an op-ed Davis wrote for the Advocate after his exoneration, he explains that at one point during his trial, all three black jurors were unsure of his guilt. “After 120 years of the non-unanimous jury rule, we have all the evidence we need to show that it worked as intended to perpetuate white supremacy,” he wrote.

A bipartisan group of backers, lead by the Unanimous Jury Coalition, agree with Davis that the time has come to do away with the state’s antiquated jury system—since his release, Davis has become a spokesman for a growing movement in the state to change the law. In Louisiana, a heavily Republican state, such consensus on one issue is rare. Tarpley, who himself is a Republican, told me that to his knowledge, there are no concerted efforts against the measure. It’s a cause liberals and conservatives can get behind, Tarpley says, for different reasons: The former see it as a chance to right the wrongs of a criminal justice system that unfairly targets people of color, while the latter see it as an opportunity to defend constitutional rights.

“This is about liberty and justice and fairness, and like I’ve told people, if you love the Constitution and you love the Bill of Rights, then you’ve got to vote for Amendment 2,” Tarpley said. “Everybody can agree on liberty.”