Tiffany Cabán in Astoria with her rescue dogCourtesy Cabán campaign

It was 2011, and Tiffany Cabán, then a law student in New York City, braced herself for an awkward class assignment: She’d have to complete an internship at the district attorney’s office in Queens, where she grew up. The office had a reputation for being tough on crime. Cabán, who dreamed of becoming a public defender, cared more about closing jails than filling them. “See you on the other side of the aisle,” she recalls the prosecutors telling her when she said goodbye at the end of the stint.

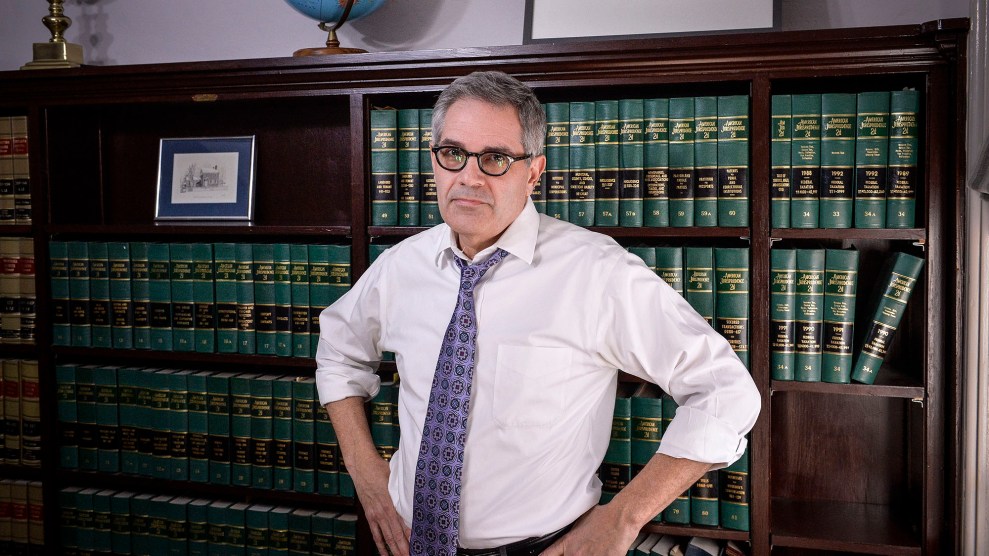

After about seven years working as a public defender, Cabán, now 31, wants to get back into that office—only this time she hopes to lead it. In January, she threw her hat into a crowded race to become the borough’s next district attorney. (Democrat Richard Brown, who has held the position uncontested since 1991, is stepping down for health reasons.) Cabán, a queer Latina, has a radical vision for the position: She says she’d incarcerate as few offenders as possible and bulk up social services offered to people who are accused of crimes. She counts among her champions the same campaign manager, Virginia Ramos Rios, who helped newcomer Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez topple former Rep. Joe Crowley in their race for Congress last year. While the stakes of the races are different, Ramos Rios sees certain parallels between the candidates: They are both “taking on positions that other folks are like, ‘There’s no way.'”

District attorneys’ offices haven’t traditionally been known as hotbeds of criminal justice reform—especially in Queens. Under Brown’s watch, the office regularly took people to court for minor offenses, like marijuana possession and fare evasion, that DAs in other boroughs have started to ignore, and its prosecutors often asked for relatively high bail. “The Queens district attorney’s office continues to live in the past,” says Alyssa Aguilera, co-executive director of Vocal-NY, a grassroots group pushing for criminal justice reform. With the primary in June, “we’re at the cusp of a huge opportunity” to end the “deadlock on progressive prosecutorial practices,” says Nicole Triplett of the New York Civil Liberties Union, which does not endorse candidates.

In recent years, DA races have started to garner more attention nationally amid a growing conversation about the immense power that prosecutors wield in the criminal justice system. Prosecutors decide which charges to pursue and which to drop, whether to request bail, and how to shape plea bargain agreements that determine the outcome of roughly 95 percent of all cases. DAs like Larry Krasner in Philadelphia and Rachael Rollins in Boston successfully campaigned in 2017 and 2018 on platforms that promised to reduce mass incarceration and tackle racial disparities in the system.

In Queens, at least seven candidates have stepped into the race. Most of them are positioning themselves as progressive and forward-looking: By and large, they’re against cash bail and a surge of immigrant arrests, and in favor of closing the jail complex at Rikers Island and prosecuting fewer broken-windows offenses.

Cabán—the only public defender of the group, and one with prison abolitionist leanings—is pushing the conversation even further left. As a district attorney, she notes, she wouldn’t be able to close prisons, but she could try to reduce the harm she believes they inflict on communities. “Our prosecutorial system is entirely broken,” she told me, “because prosecuting right now means convictions and sentences rather than asking two simple questions: How do we make sure this harm doesn’t happen again, and how do we make our communities safer in actuality?”

Cabán was born in Queens’ Richmond Hill neighborhood to Puerto Rican parents. Her dad, an elevator mechanic, and her maternal grandfather, an immigrant and military veteran, both struggled with alcoholism, something that later shaped her view of the courts and incarceration. During his worst years, she says, “my grandfather was incredibly physically abusive, to the point where my grandmother left him and my mom dropped out of high school to help support the family. But the man I got to know was this kind, patient, loving abuelo.” As she got older, it bothered her that the criminal justice system didn’t take into account these kinds of complexities. “The current system does not look at a man like my grandfather—a dirt-poor kid from Puerto Rico and a Purple Heart recipient from his service during the Korean War who self-medicated with alcohol—and ask, ‘How have we failed him and how can we now support him?'” she wrote recently. “I always ask that question.”

Tiffany’s not just a career public defender. She’s also a Queens native, a queer Latina, and a working-class New Yorker. And she’s clear about how that lived experience informs her passion for delivering on an agenda of radical decarceration here in Queens: pic.twitter.com/JouOlLqusq

— Matthew Thomas (@MattThomasNYC) February 26, 2019

After graduating from New York Law School, Cabán took a job as a public defender at the Legal Aid Society and later the New York County Defender Services. She soon grew frustrated that many of the people she saw prosecuted and jailed for nonviolent crimes were mentally ill or desperate, and when they were pulled from their housing, jobs, and family, they were further destabilized. In her campaign for DA, Cabán pledges not to charge people for a slew of crimes like drug possession and fare evasion.

And in a stance that sets her apart from her competitors, Cabán would also decline to prosecute sex workers and their clients. In New York, arrests for loitering for prostitution jumped 180 percent from 2017 to 2018, with roughly half of those occurring in Queens, suggesting that sex workers in the borough, especially women of color, are at increased risk of being targeted by law enforcement. Several other candidates have pledged not to prosecute sex workers but to continue charging customers—a tactic that Cabán argues would still drive sex workers underground and make them vulnerable.

Critics argue that leniency toward customers could perpetuate human trafficking. It is “very dangerous to women who have been trafficked and doesn’t really represent a comprehensive criminal justice reform policy that has the protection of women at the center of it,” says City Councilman Rory Lancman, a reformist candidate in the race, who has called himself the “Larry Krasner of Queens” and has worked with the City Council to fund services for people accused of sex-work offenses. Cabán counters that fully decriminalizing the industry will actually help law enforcement fight trafficking, because sex workers might be more likely to ask police for help if they know they won’t lose their jobs or wind up in jail for doing so.

Cabán also opposes the city’s plan to build or expand jails in four boroughs as a replacement for the eight jails on Rikers Island, which are slated for closure by 2027. “Every time new jails are built throughout this country’s history, they are filled—and overcrowded,” she explains on her website. Queens already has a dormant jail facility that the city wants to make bigger. Cabán thinks this is unnecessary and that the DA’s office should reduce the inmate population by declining to request bail and investing more in community-based services that would be available before offenders are charged or even arrested, no strings attached. She wants constituents to decide how to spend some of the DA office’s budget, particularly the $100 million it has gotten from federal civil asset forfeiture, ideally funneling it to hospitals, schools, job training, and affordable housing for people accused of crimes. “We need to divest from the DA’s office and invest back in our community-based organizations—to do everything we can to prevent initial contact with the criminal justice system in the first place.”

The idea of keeping offenders out of prison and linking them up with housing, health care, and job training isn’t new. In 2011, Seattle began encouraging police to connect drug offenders with housing and health care instead of arresting them. A study by the University of Washington found that people who went through this program, called LEAD, were 58 percent less likely than others to recidivate. And district attorneys across the country fund diversion programs that offer some of these services for low-level offenders and others grappling with poverty and mental health problems. But in Queens, defendants are often pressured to take a conditional plea deal before they are screened for these diversion programs, which can be strict and come with fees. Cabán would not require defendants to plead before this screening. “The rule should be services, then diversion, and almost never should someone be incarcerated,” says her policy director, Alon Gur.

Some have slammed Cabán’s stance on the replacement for Rikers. Lancman says that without a bigger jail in Queens, inmates would be held farther from their families and would have to travel in and out of the borough for court dates. And others say her aversion to incarceration ignores the reality of what the job is about. “The district attorney’s office is not the public defender—the district attorney is the prosecutor,” adds Lupe Todd-Medina, senior communications adviser for candidate Mina Malik, who worked in the Queens district attorney’s office for 15 years. “Those that need to help, whether they have substance abuse problems or mental health issues—we’re going to help them. But it’s a law enforcement office.”

Cabán faces some stiff competition. Melinda Katz, the Queens borough president and a former Democratic Assembly member, has more than $1 million at her disposal, some leftover from prior political campaigns. So does Lancman, who also served in the Assembly and has been endorsed by Gwen Carr, the mother of Eric Garner, whose killing by New York police in 2014 set off a wave of protests. Also in the running are Jose Nieves and Betty Lugo, who have both worked as prosecutors, like Malik. Greg Lasak, a former Queens Supreme Court judge and county prosecutor, has raised more than $800,000 to date, with endorsements from law enforcement unions.

But Cabán, who has pledged not to accept corporate donations, has racked up key endorsements of her own, including from Akeem Browder, whose brother Kalief killed himself after he was locked up for three years at Rikers as a teenager for a minor theft charge that never went to trial. She is also endorsed by Shaun King’s Real Justice PAC, a group pushing to elect progressive prosecutors. And she has the backing of the local Democratic Socialists of America, a group not typically involved in district attorneys races. “DAs are in the business of locking people up, and that doesn’t really gel with most socialist belief systems,” says Philip Henken of the DSA’s Queens branch. But “Tiffany definitely has a radical approach.” The group is now trying to collect the signatures Cabán needs to get on the ballot for the June 25 primary. “I wouldn’t be surprised if their activity [and] endorsement means something considerable, even in Queens, which still has conservative areas,” Baruch College political scientist Doug Muzzio told the Gotham Gazette, a New York–based online publication. The DSA’s door-knocking last year helped Ocasio-Cortez clinch her seat in Congress.

There are certainly doubters. Queens County Democratic Party spokesman Michael Reich questioned Cabán’s ability to beat Katz, who has been endorsed by the local party, saying Cabán is too young. She “doesn’t have enough years of experience to be nominated for a judgeship,” he told the Queens Daily Eagle. Lancman piled on to that criticism, saying that while he has worked for years in government to expand supervised release programs and fund citywide bail funds, “Tiffany’s engagement with criminal justice reform is very limited.”

But Cabán, who notes that she juggles 65 to 80 criminal cases at a time as a public defender, isn’t deterred. “The pushback to progressive reforms is inevitable,” she wrote recently of her platform. “We stand up tall, dig our heels in, and brace ourselves.”