LightFieldStudios/iStock/Getty

Growing up, Ameer Baraka dreaded spelling tests. On Fridays, when his class took them, he would often skip school and hide in the hallways of the New Orleans housing project where he lived. Other parts of school made him miserable, too—the way his classmates would point and laugh when his teacher would ask him to read a passage aloud and he couldn’t make out the words, his palms sweating from the stress of it. By sixth grade, he’d had enough, and he decided he would drop out and start selling cocaine. At the age of 23, he landed in prison for a drug offense.

By that time, Baraka was still only at a third-grade reading level. His fellow inmates were no better off: Only one man in his intake group had a high school diploma. Baraka wouldn’t find out until later that he had dyslexia, a reading disorder that affects an estimated 15 percent of the general population and likely an even higher proportion of inmates—many of whom were not diagnosed in school and later dropped out.

No national studies have been done to show the prevalence of dyslexia among prisoners, but the little research that exists at the state level suggests the rates are quite high: A 2000 study of Texas prisoners found that about half were likely dyslexic, and about two-thirds struggled with reading comprehension. A 2014 study by the Education Department found that about a third of incarcerated people surveyed at 98 prisons struggled to pick out basic information while reading simple texts. Still, most prisons historically haven’t conducted widespread screenings for dyslexia—making it hard for prisoners with the reading disorder to make up lost ground while they’re behind bars.

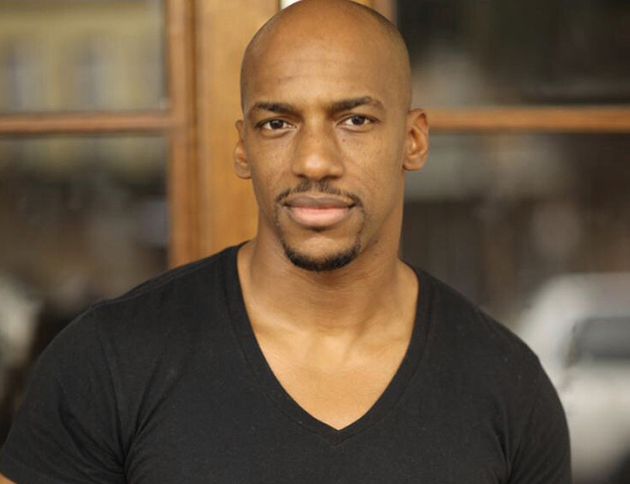

Ameer Baraka

Courtesy Dyslexia Awareness Foundation

That may finally be changing. A major criminal justice reform bill that passed Congress in December, the First Step Act, will require federal prisons to screen for dyslexia at intake, and to provide services that will help people learn to read if they are diagnosed. This component of the law was pushed by Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-La.), who encountered many illiterate patients while running clinics in three Louisiana prisons as a doctor before he became a lawmaker. His wife, Dr. Laura Cassidy, tested men for dyslexia in two of those prisons in 2018, and more than half were thought to have the condition.

By helping to diagnose more people, Sen. Cassidy says the First Step Act will make it easier for them to find employment after their release. “If someone learns to read, they’re less likely to end up in prison and more likely to be a productive member of society,” he says. A study by the Rand Corp. found that prisoners who participated in education programs were 43 percent less likely to commit crimes later on.

But federal prisons account for a relatively small slice of the country’s incarcerated population: roughly 171,000 people, compared to more than 1.3 million in state prisons. The First Step Act won’t affect state prisons, most of which do not conduct widespread dyslexia screenings for their inmates, according to staffers in Sen. Cassidy’s office who have studied the issue. And the incidence of learning disorders may be even higher in state facilities, which hold fewer white-collar offenders and more high school dropouts. (The Federal Bureau of Prisons says 40 percent of state inmates lack a high school diploma, compared with about 27 percent of federal offenders.)

After Baraka entered the Avoyelles Correctional Center, a state prison in Louisiana, he found a seat at the back of his GED class and quickly fell behind. A teacher eventually noticed him struggling and had him diagnosed with dyslexia, but he says nobody stepped in afterward to help him learn to read. This special assistance is crucial for people with dyslexia, who often have very high IQs, but whose brains may be wired in a way that makes it harder for them to decode words and recognize their sounds, something that people without the condition can often pick up more naturally. In an ideal world, “somebody will sit with them one on one and teach them the underlying structure of the language in a really explicit and multisensory way,” says Kelli Sandman-Hurley of the Dyslexia Training Institute, a California-based group that provides services like this to students.

Baraka decided to learn to read on his own, using a dictionary. “Everything I didn’t know, I just wrote it down, went over and over these words,” he says. “That’s the hardest way to learn how to read,” says Dr. David Hurford, a psychologist at Pittsburg State University who specializes in dyslexia and reading disorders. He says it’s crucial for people to correlate letters with sounds rather than just memorizing the way words look on the page.

Baraka mentoring men in prison

Courtesy Dyslexia Awareness Foundation

The First Step Act requires federal prisons to offer better reading services to inmates with dyslexia, including audio technology to assist them with schoolwork. But there are concerns among some lawmakers about the Federal Bureau of Prison’s ability to implement the law as written. The Justice Department has already missed key deadlines in the process of developing a risk assessment tool that will be tied to the dyslexia screening and determine which prisoners receive certain services. “I don’t see a lot of good faith in implementing this law right now,” Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) said in a recent hearing, noting that the Justice Department did not set up an independent committee to help develop the risk assessment tool until months after it was supposed to.

Congress, meanwhile, has failed to fully fund the First Step Act, which, in addition to changing protocols for dyslexia screening, also reformed sentencing policies and required the Justice Department to create more rehabilitation programs for federal prisoners. And President Donald Trump—despite touting the law as one of his only bipartisan successes—did not request nearly enough money in his 2020 budget proposal to adequately support its programs. All of this has left some criminal justice reform groups worried about the law’s fate. “The Department of Justice and Bureau of Prisons are committed to fully implementing the First Step Act, and to doing so within the deadlines in the statute,” a bureau spokesperson told Mother Jones in a statement; the bureau did not answer questions about what the dyslexia screening process would entail or how it would be developed, or about when the specialized reading services would be offered.

Eventually, Baraka learned enough to finish the Autobiography of Malcolm X. The story in some ways mirrored his own: The civil rights leader wrote about dropping out of school as a kid and later teaching himself to read in prison by memorizing words in the dictionary. The book helped Baraka to believe that he could also succeed one day on the outside, and he earned his GED shortly before finishing his four-year sentence. When he got out, he moved to California, enrolled in acting classes, and landed a role as a detective on the TV crime drama Bronx SIU, for which he recently earned an Emmy nomination as a supporting actor. He also launched the Dyslexia Awareness Foundation, which, together with Dr. Hurford and Pittsburg State’s dyslexia center, is reaching out to state corrections systems and offering to screen inmates for dyslexia.

The foundation also aims to work with schools and improve screening for young kids. According to Sandman-Hurley, a majority of states don’t require schools to test all their students for the condition, which means many children never get the assistance they need. “If you have these kids who don’t really have the support of their family, someone who can hire five tutors, then it’s unlikely they’re gonna finish high school, and if you don’t finish high school then you run into trouble,” she says.

“When you can’t read, you see no other way out,” says Baraka. “As a kid, I used to ask God to make me a drug dealer, because I knew in order to be someone in life you have to learn to read, and I couldn’t.” When he was finally diagnosed and earned his GED, “I started viewing myself in a different way,” he says. “When I learned to read, it freed me.”